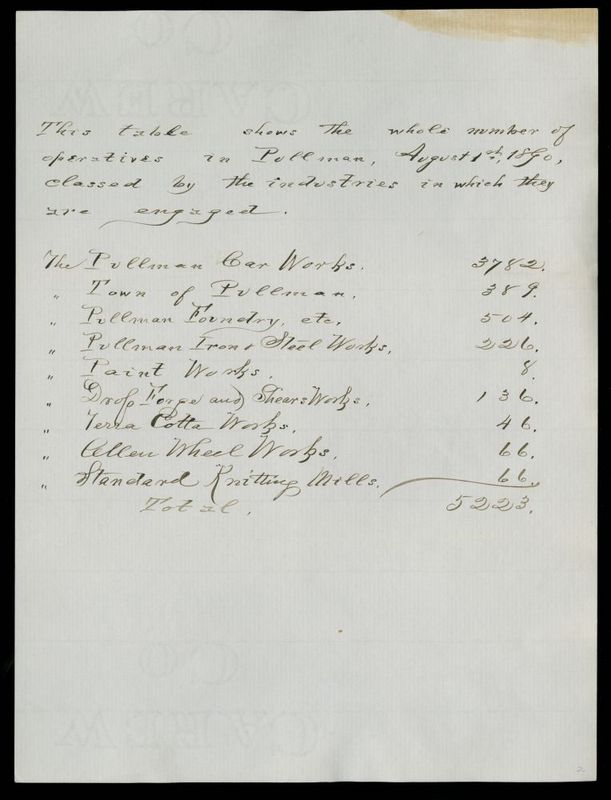

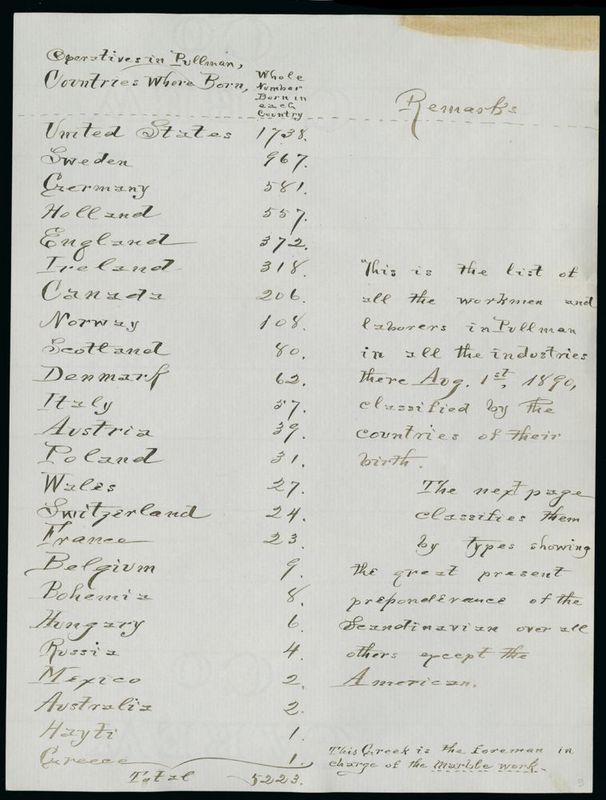

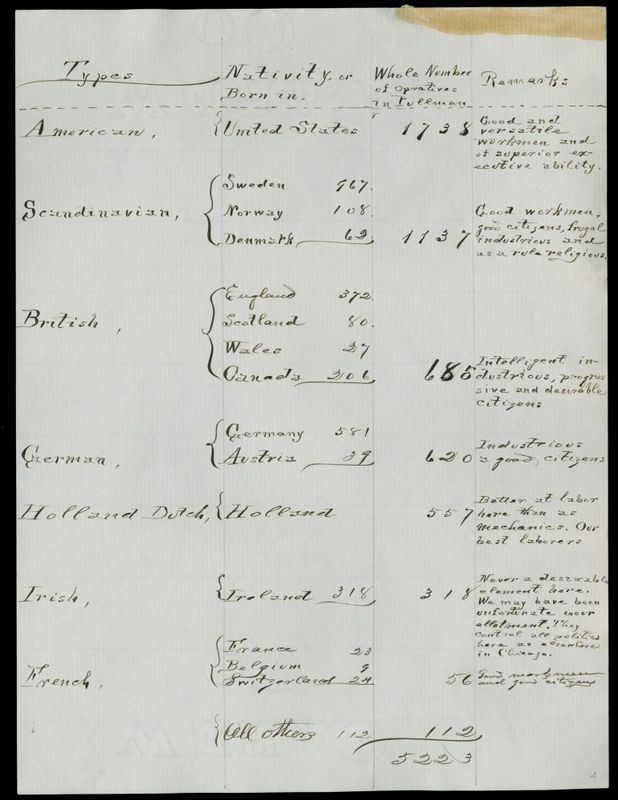

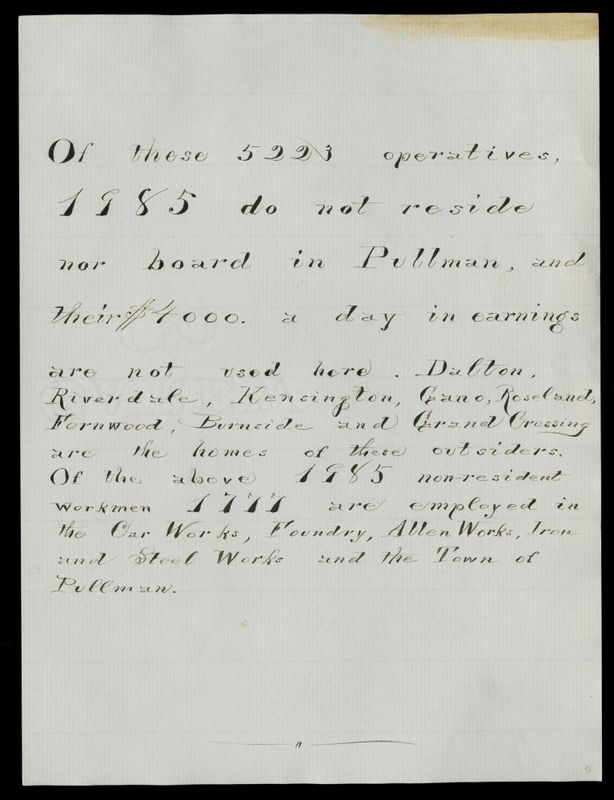

In the Town

Luxury on Wheels

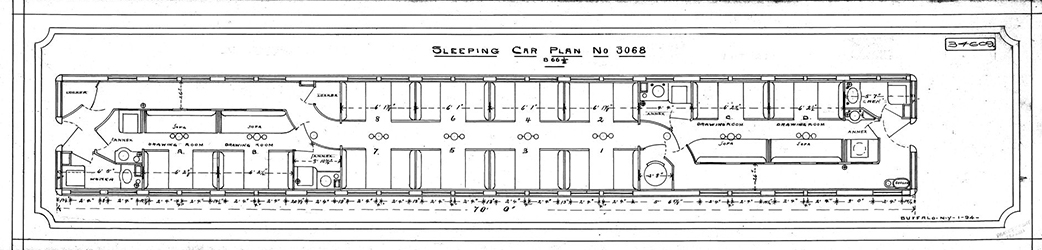

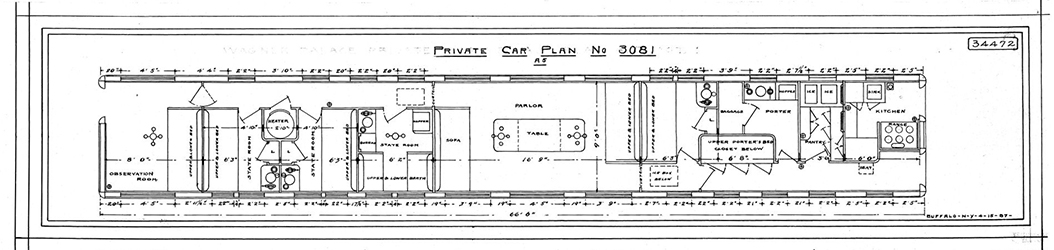

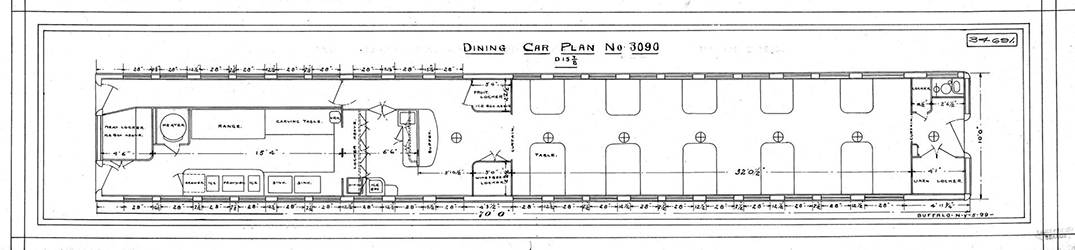

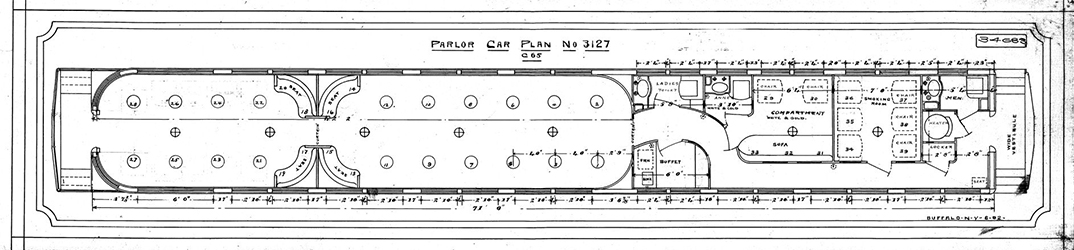

In many ways, George Pullman intended his Palace Car Company to counter the discomfort, disorder, and discontinuity endemic to rail travel and modern urban life. As early as 1860, before his company had even existed, Pullman had been experimenting with railcar construction by outfitting his cars with sleeping berths that could be folded into chairs during the day. The innovation made Pullman’s cars wider than standard railcars, which initially prevented most railroads from carrying them on their narrower rails. After George Pullman secured the right for one of his cars to serve as Abraham Lincoln’s funeral car in 1865, interest in Pullman’s sleeping cars greatly expanded. In 1867, Pullman incorporated Pullman’s Palace Car Company with several investors and devoted himself to manufacturing sleeping cars.

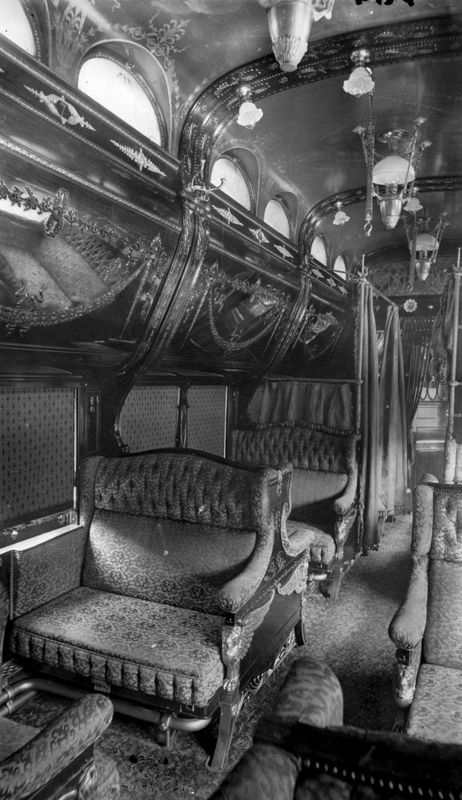

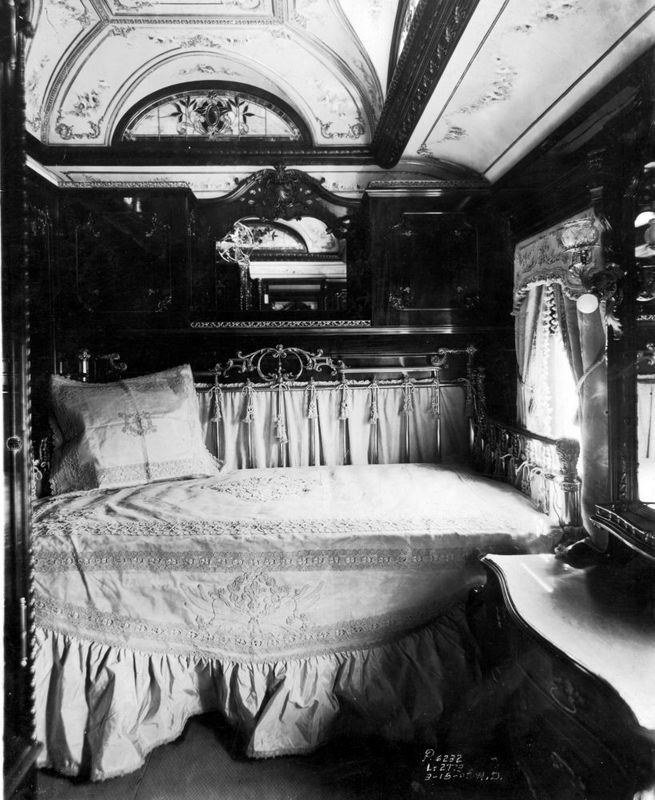

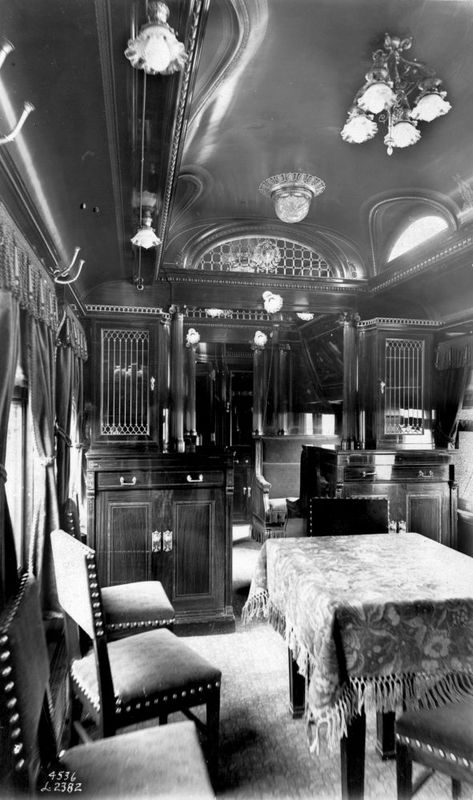

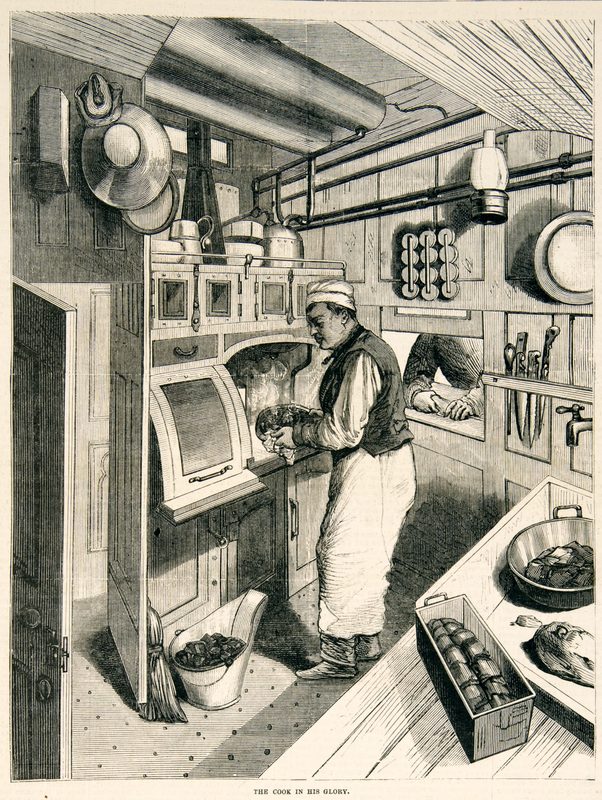

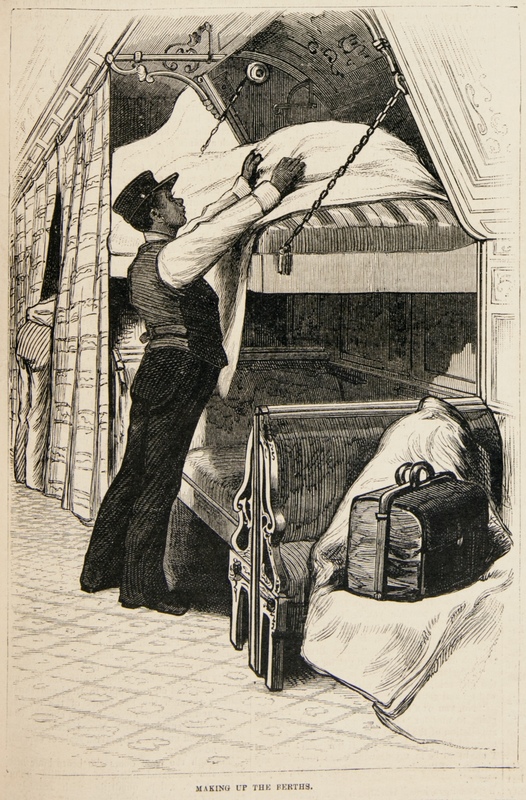

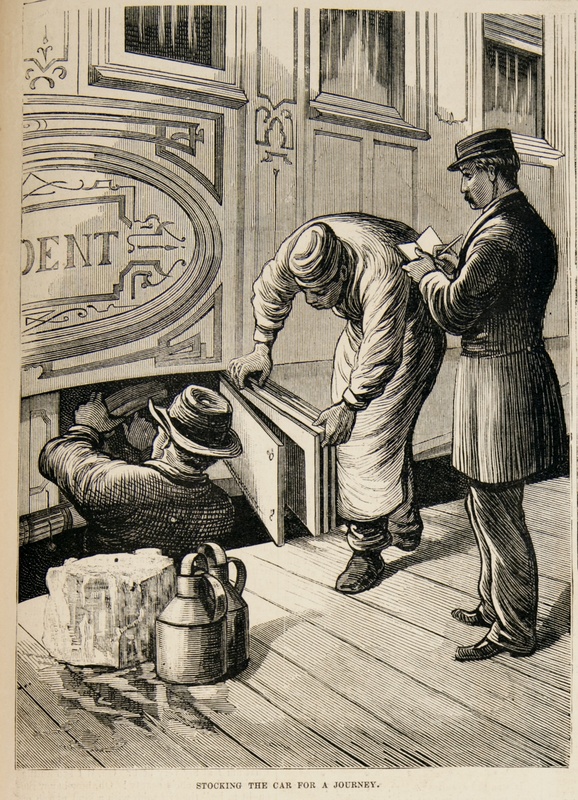

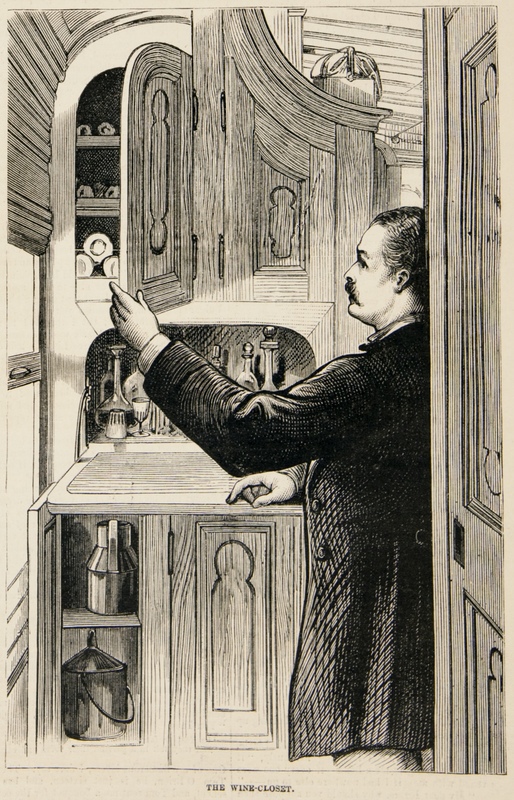

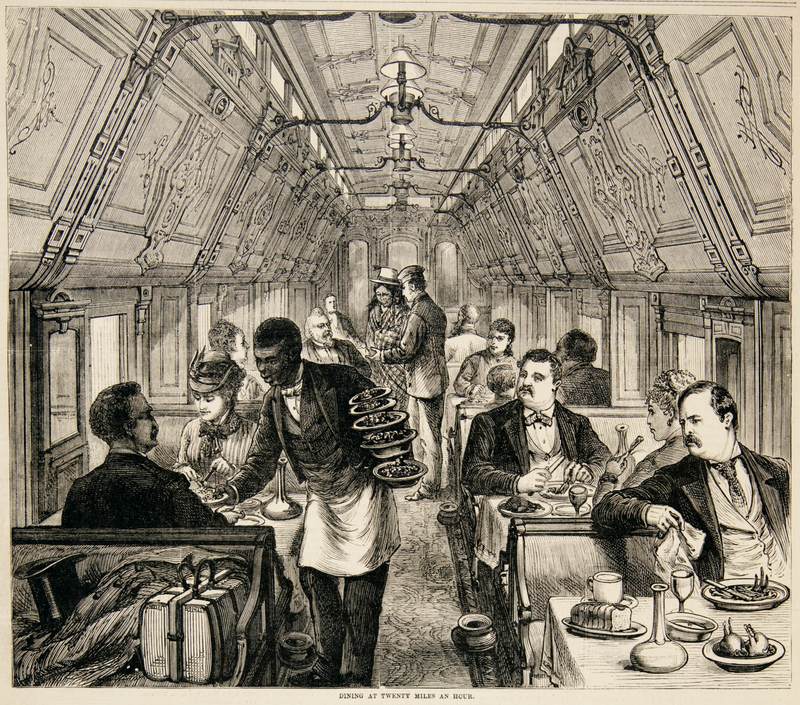

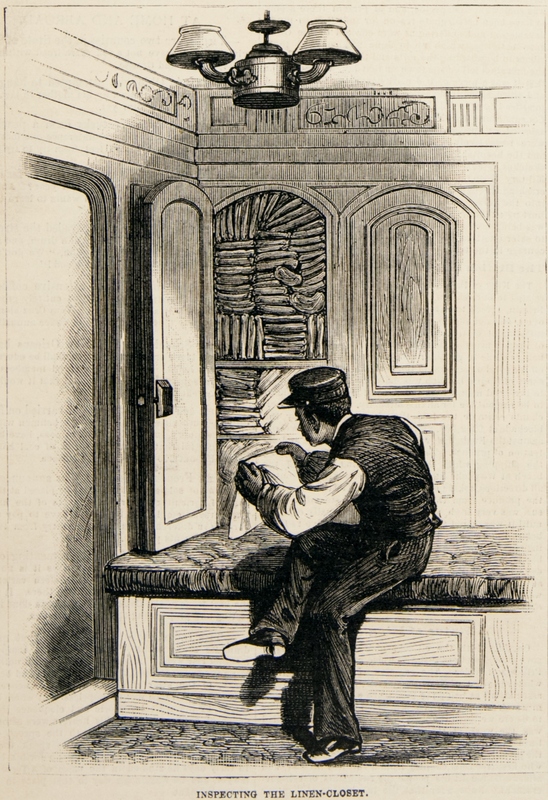

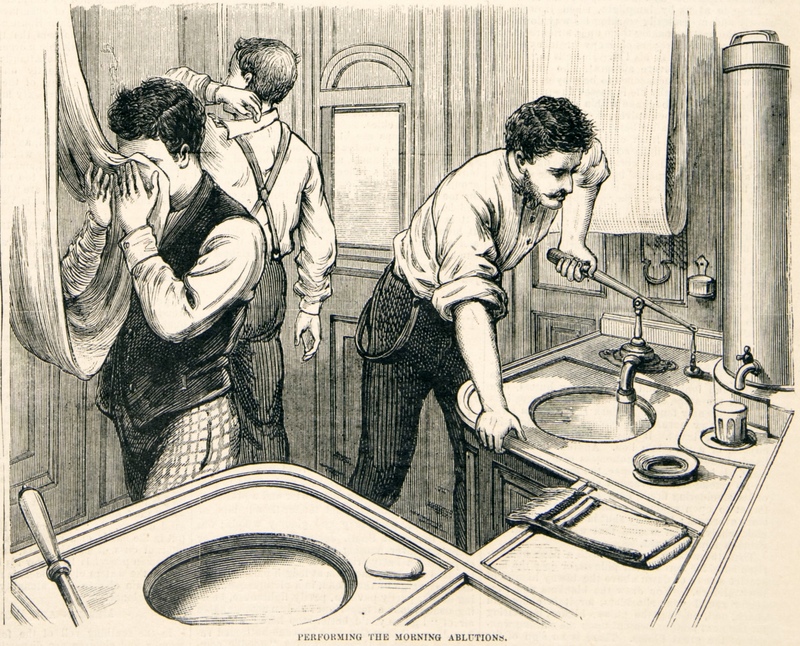

But Pullman did more than simply manufacture sleeping cars. He also focused on transforming the entire experience of rail travel. As the photographs and documents below convey, Pullman emphasized the palatial aspects of his railcars. Outfitted with plush seating and ostentatious decorations, Pullman cars were intended to bring order and comfort to modern rail travel.

Scenes from a Pullman Car

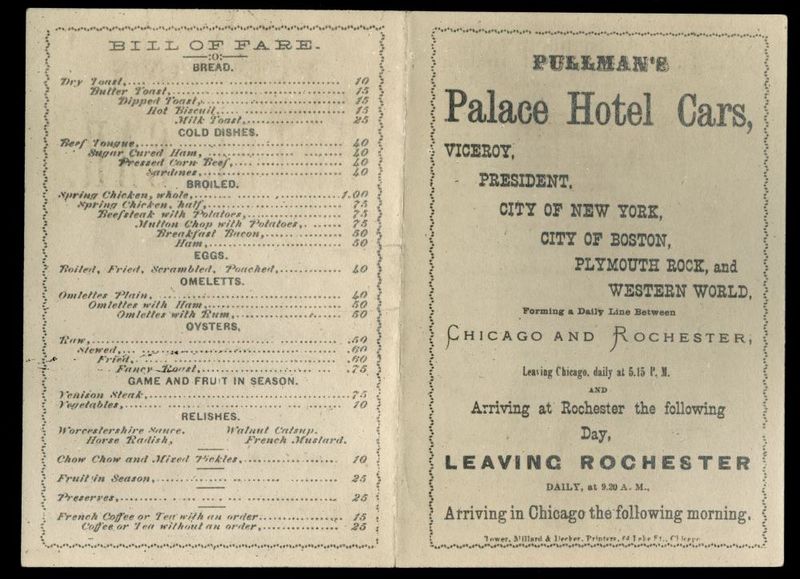

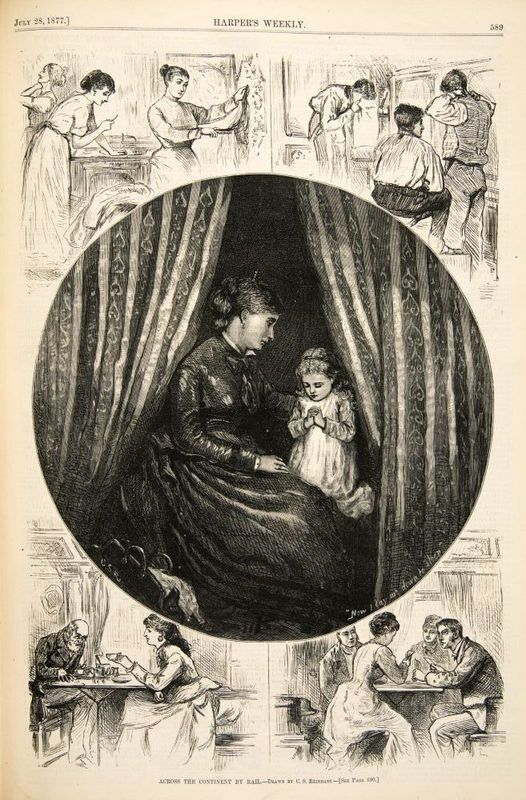

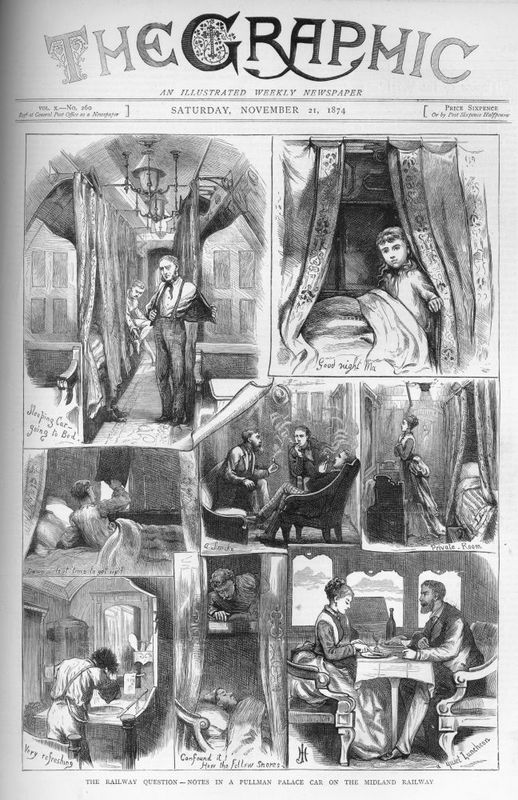

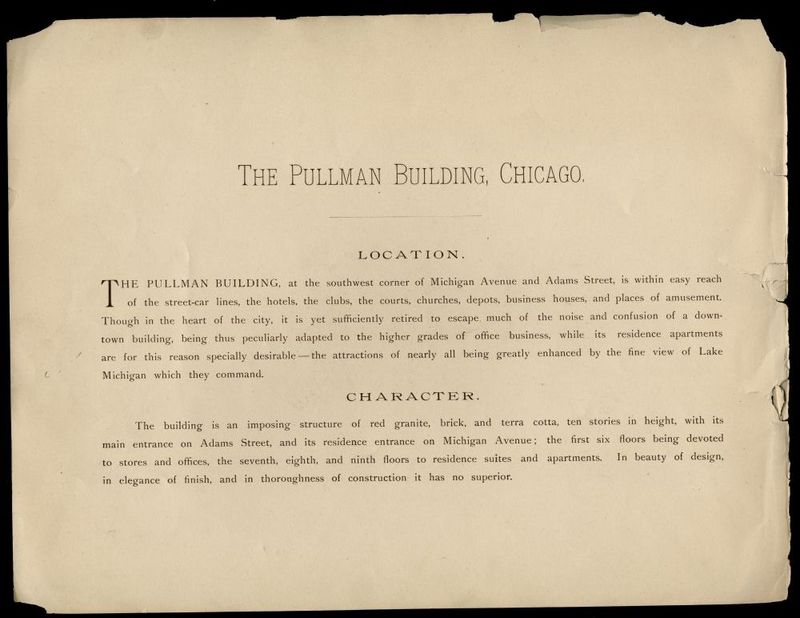

In addition to manufacturing luxurious sleeping cars, George Pullman also spent considerable time and energy crafting a luxurious image for the Pullman Company. Through advertisements and well-placed journalistic reports, Pullman was able to make both his name and his company synonymous with high-class service and travel. These illustrations, articles, and published materials reflect these popular perceptions of Pullman and the image he so carefully crafted.

An Industrial Vista

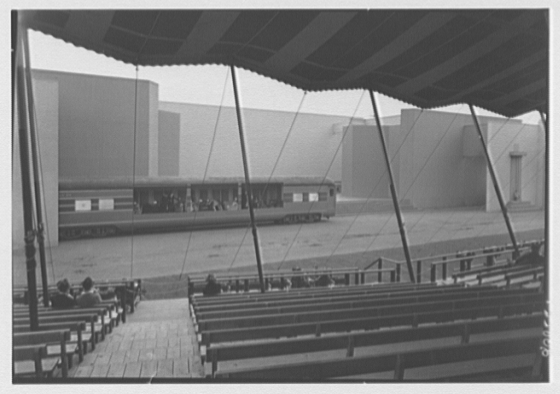

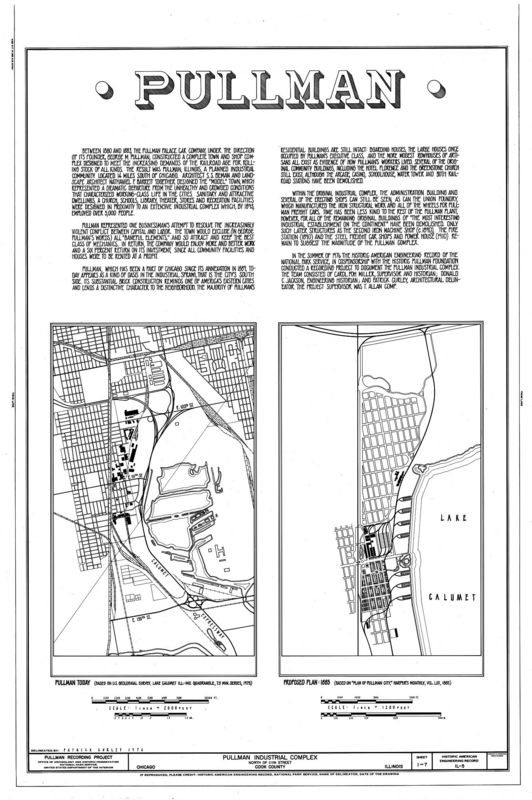

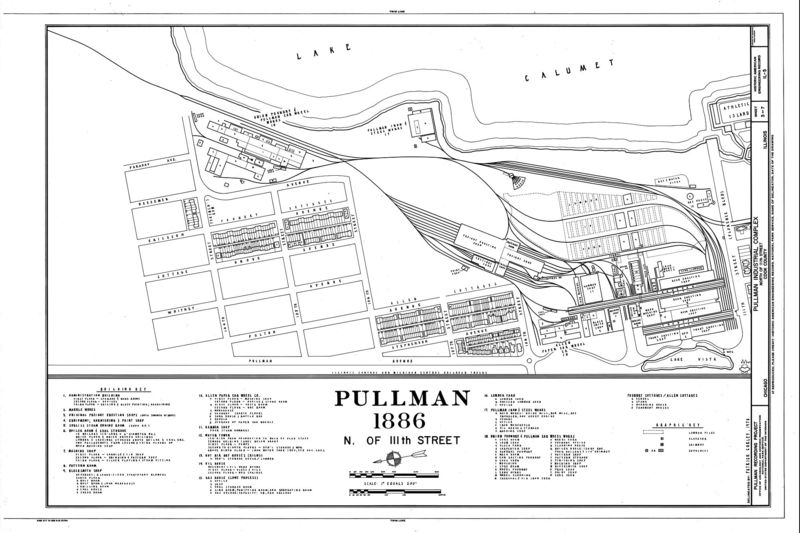

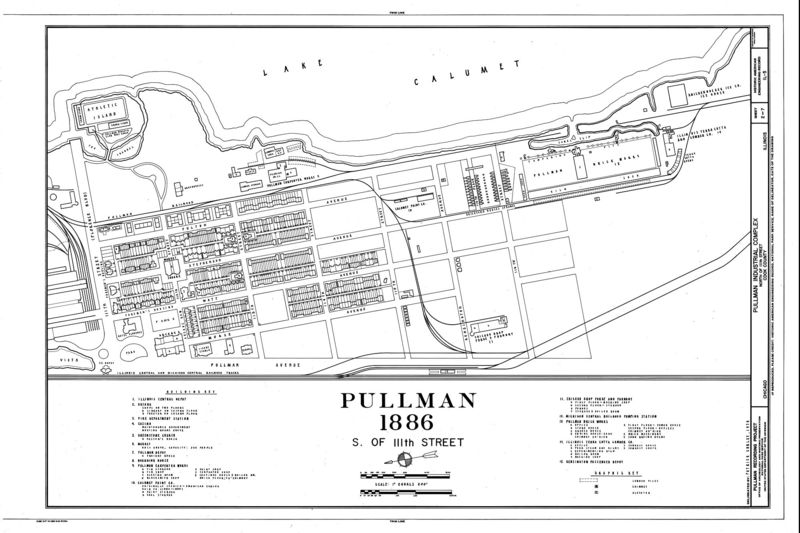

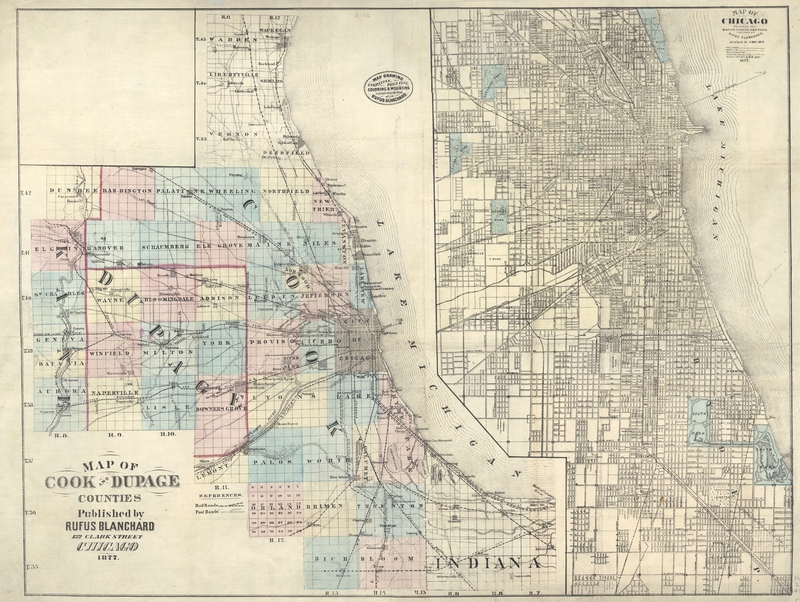

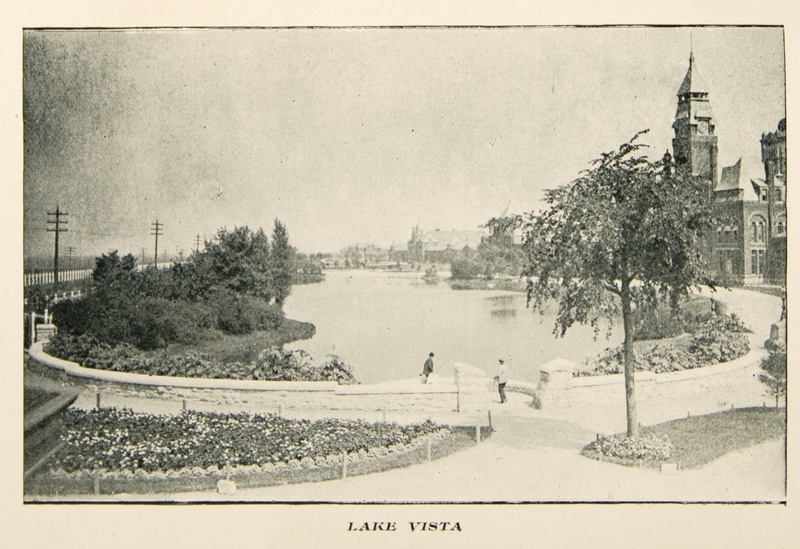

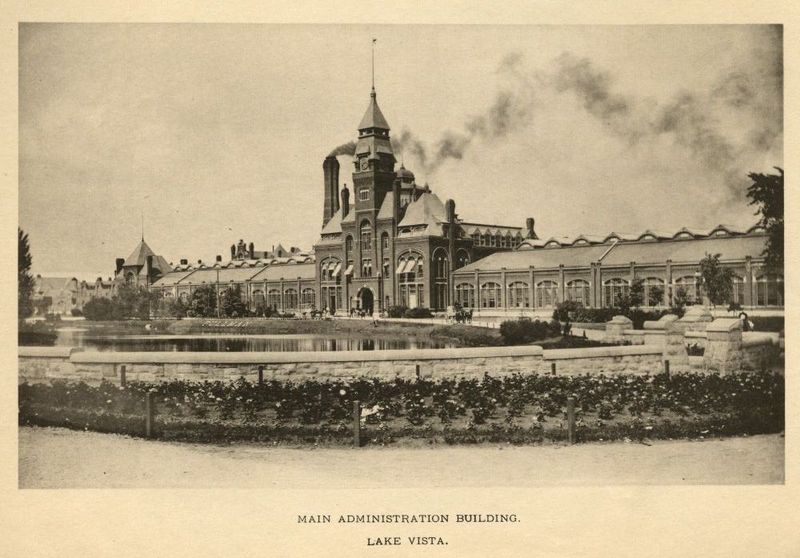

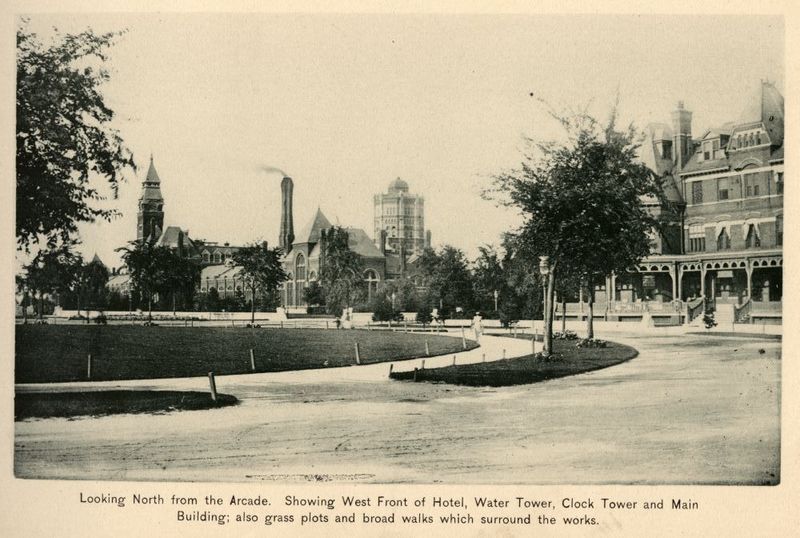

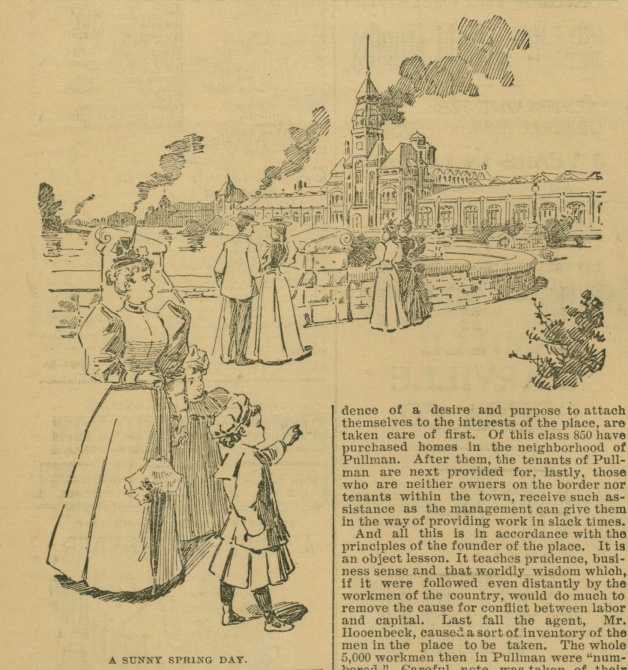

Pullman’s attempt to make his company synonymous with order, grandeur, and progress did not end with his sleeping cars. It also extended to their production. In 1878, Pullman began scouting locations to build a number of new factories. He eventually selected an isolated, unsettled patch of Illinois prairie fifteen miles south of downtown Chicago along the Illinois Central Railroad near lake Calumet. There he would centralize most of his company’s manufacturing. From the very beginning, however, it was clear that Pullman intended the site to be far more than just a site of production. The very distance between Pullman’s factories and Chicago conveyed his desire to remove his company from the discomforts of urban life. The factories’ fashionable architecture and decorative landscape further suggest Pullman intended their physical distance to embody a more profound cultural difference. And as the park and Hotel Florence begins to reveal, Pullman’s plans for his new factories were but a part of an even broader social vision.

Homes for the People

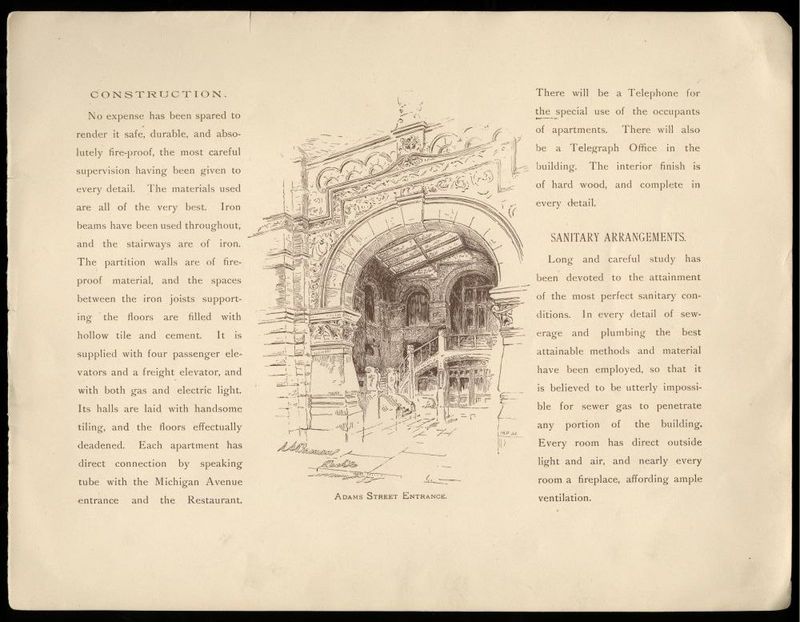

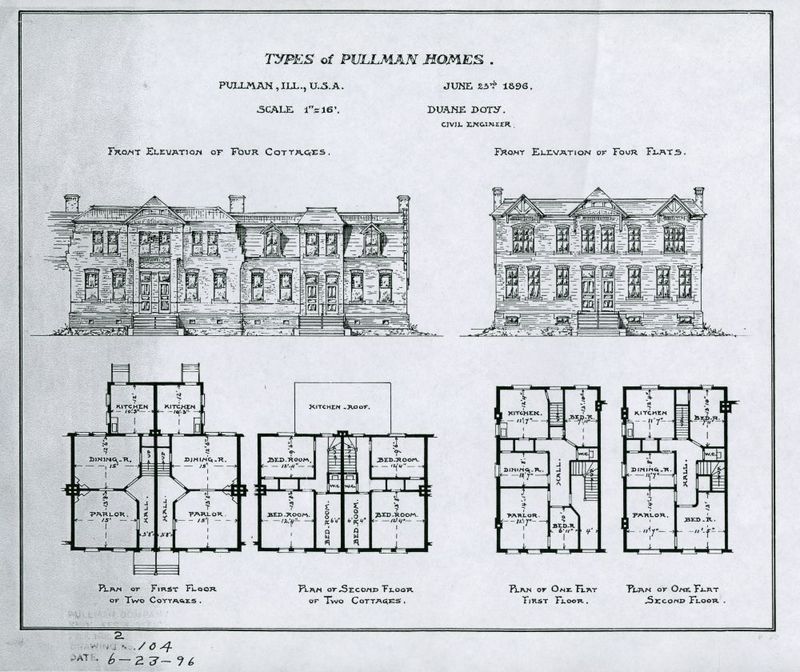

As sites of industrial production, George Pullman’s new factories were unique in their meticulous landscaping and architectural beauty. The extent of Pullman’s social vision for the site, however, was clearest when one moved beyond the factories. Surrounding the factories, Pullman constructed hundreds of homes for the company’s workers. There were multistory units for managers, townhomes for skilled craftsmen, and even apartment buildings for day laborers. The Pullman Company owned the residences and leased them to interested workers who could have their rent withdrawn from their paychecks. Pullman’s new site south of Chicago, then, was not only be a center of production but also of community.

A Model Town

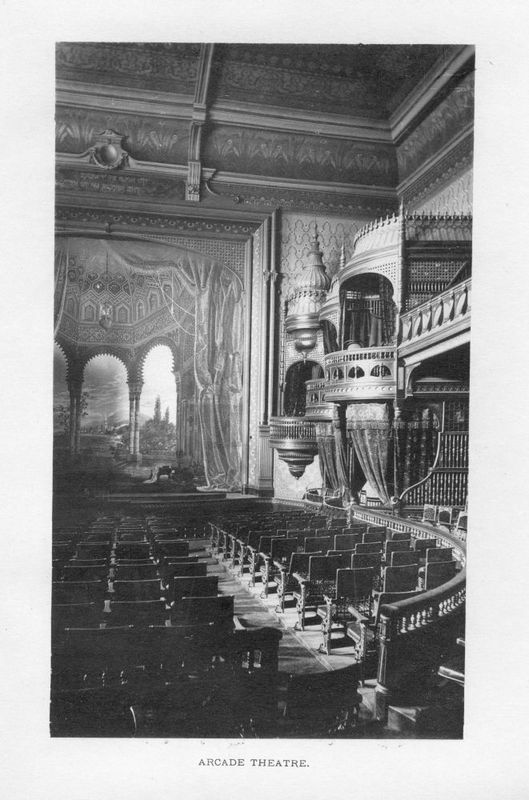

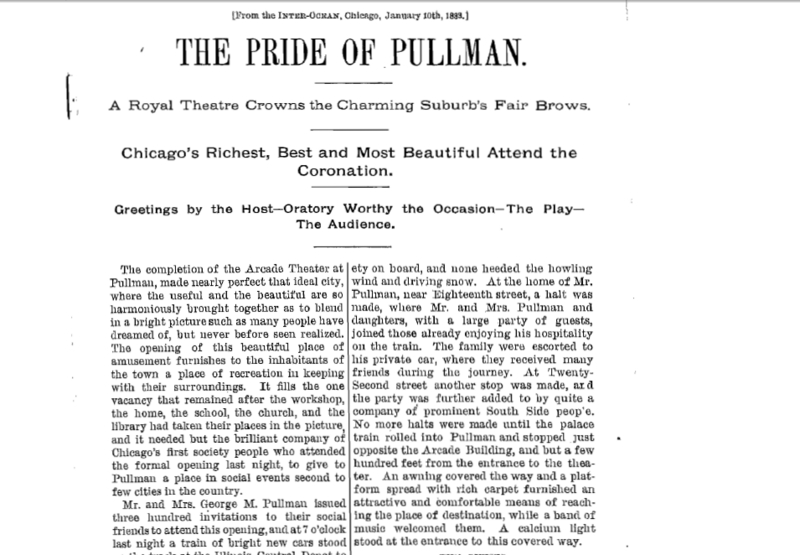

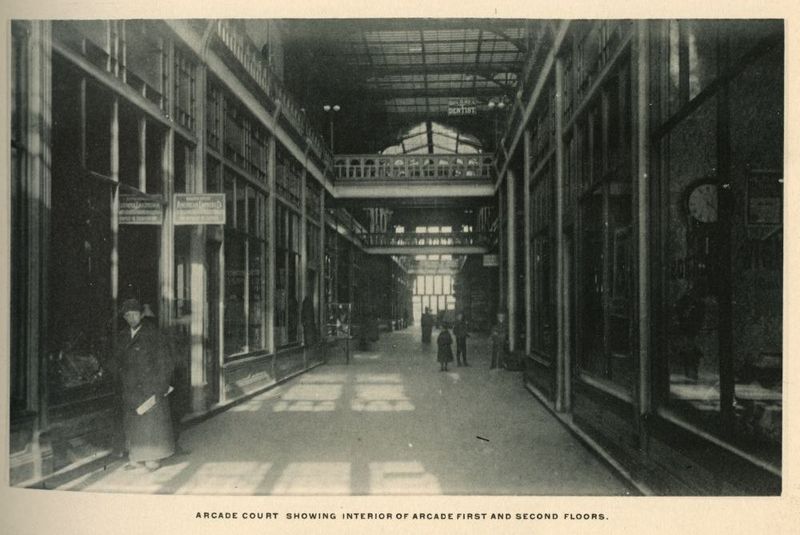

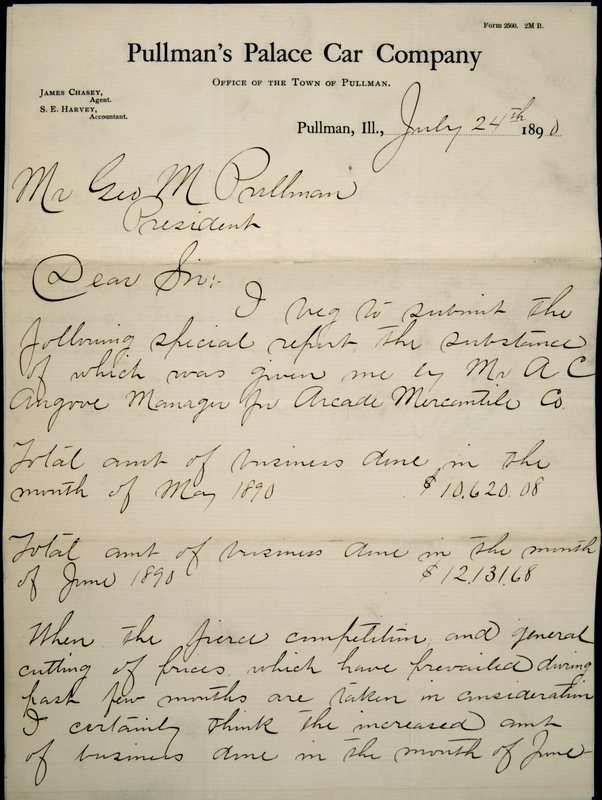

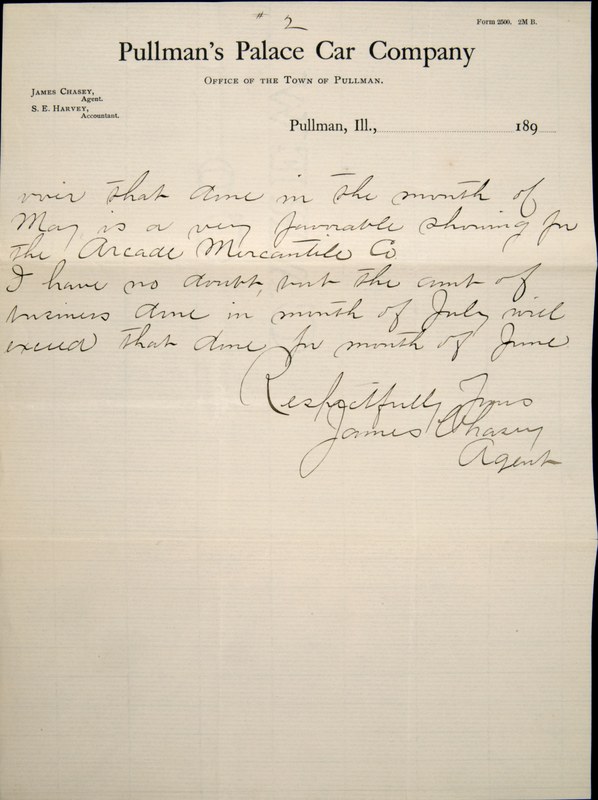

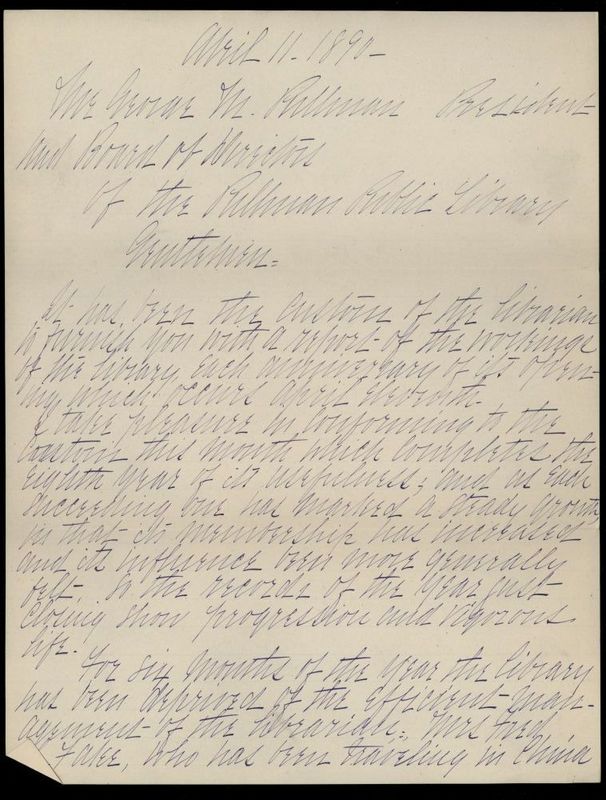

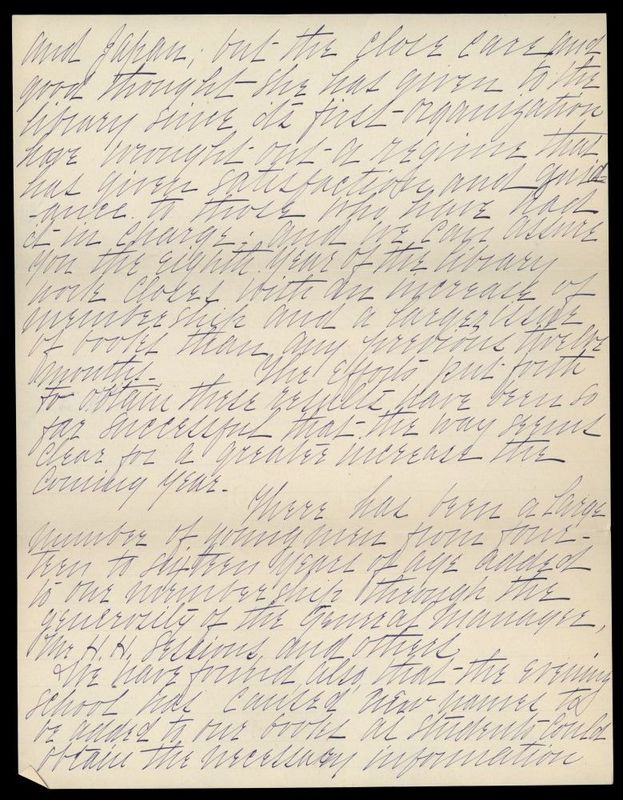

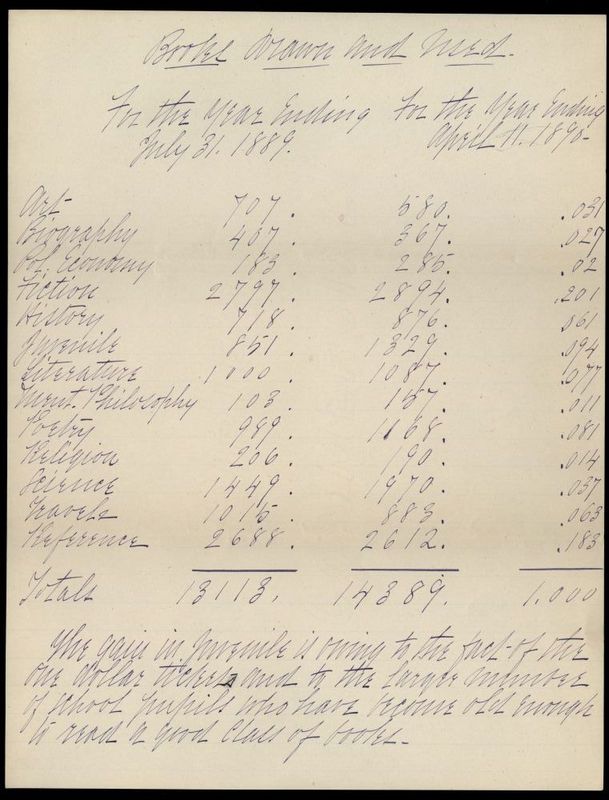

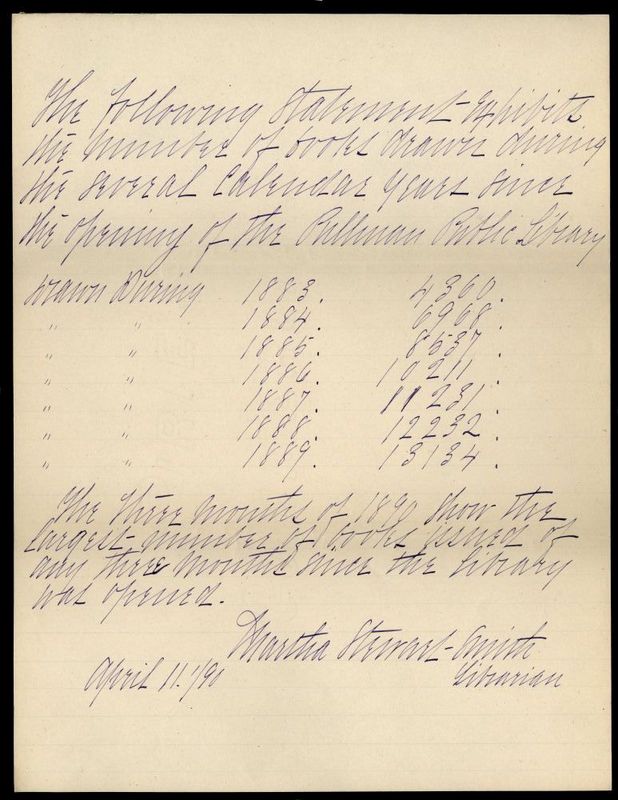

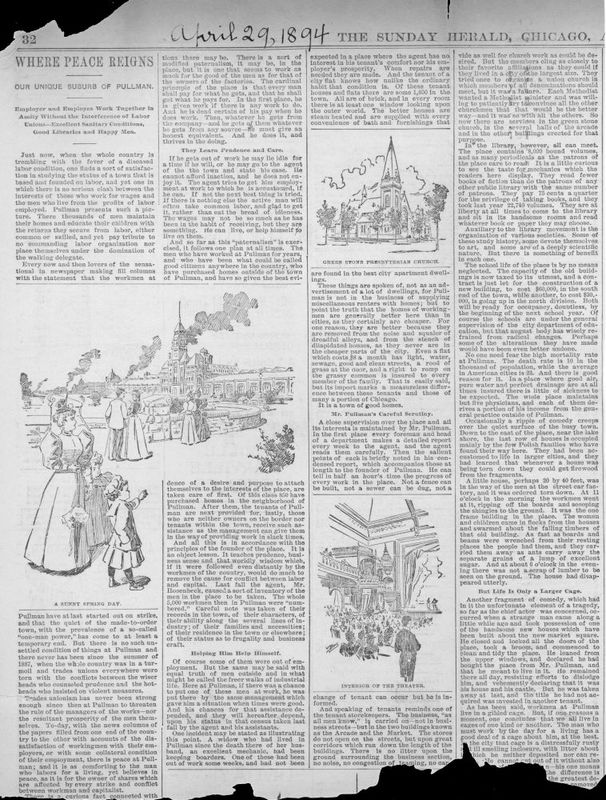

George Pullman completed his community by building a fully functioning town around these homes and factories; a town that he, of course, named Pullman. This town of Pullman had its own school, theatre, arcade, hotel, library, and church that were all owned and operated by the company. Each institution in its own way contributed to the company’s bottom line through their profits, while also helping to create a vision of the town as peaceful, virtuous, prosperous, and productive. The bar inside the Hotel Florence, for instance, was the only place in town that sold alcohol, and Pullman set the rent of the Greenstone Church so high that every religious faith would have to cooperate to occupy it. Similarly the library, theatre, and general store all provided the community not only with services, but also with what Pullman considered to be proper moral surroundings. All, he believed, would foster quiescent workers and a broader social harmony.

Where Peace Reigns

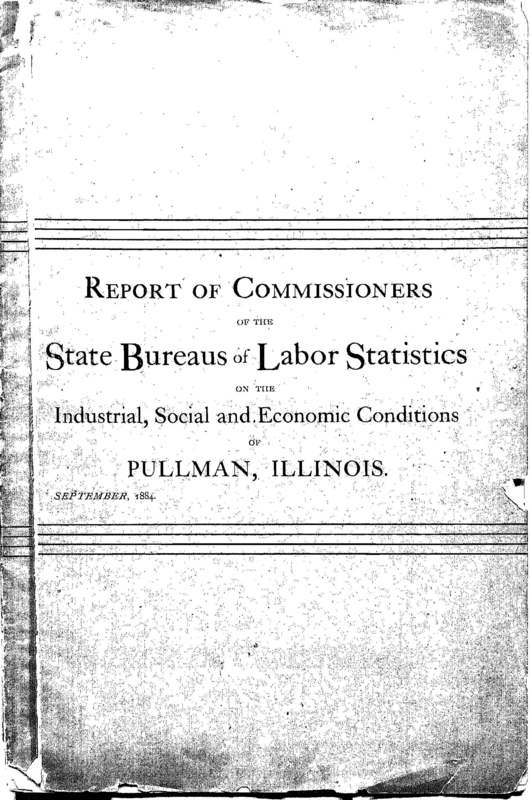

Many in the general public greeted this new town of Pullman as a grand social experiment, an attempt to solve or alleviate many of the problems endemic industrial life. Journalists, academics, and politicians all flocked to Pullman to study how it worked, determine if it was successful, and plan to replicate its practices. Capitalists marveled at its efficiencies, bureaucrats admired its comprehensive services, and members of the general public praised its seeming cross-class harmony. Many observers, however, also noted that this tranquility came at the expense of the company serving as a kind of autocrat over the town.