In the Neighborhood

From Town to Neighborhood

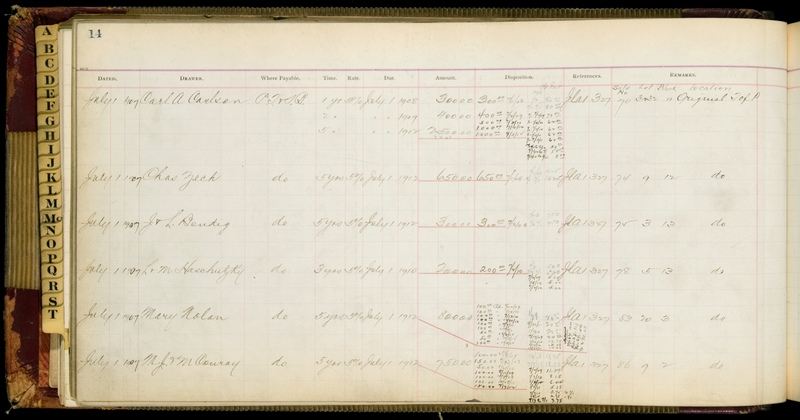

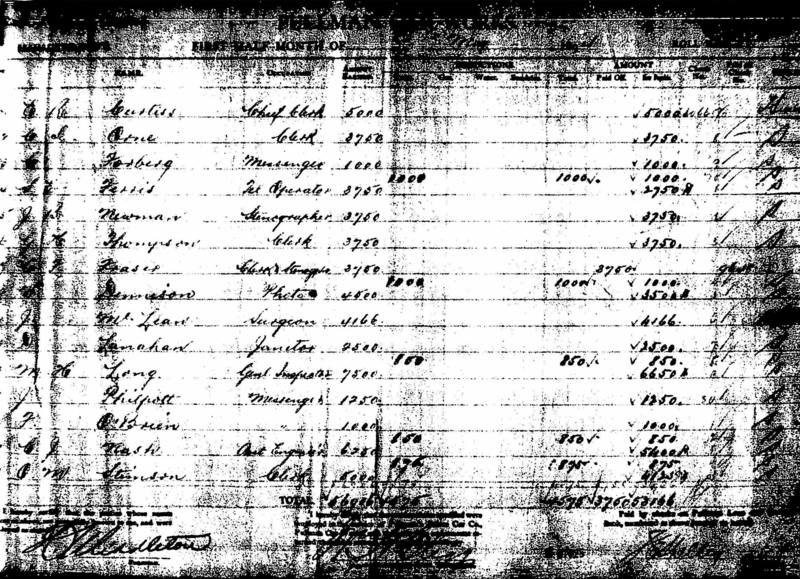

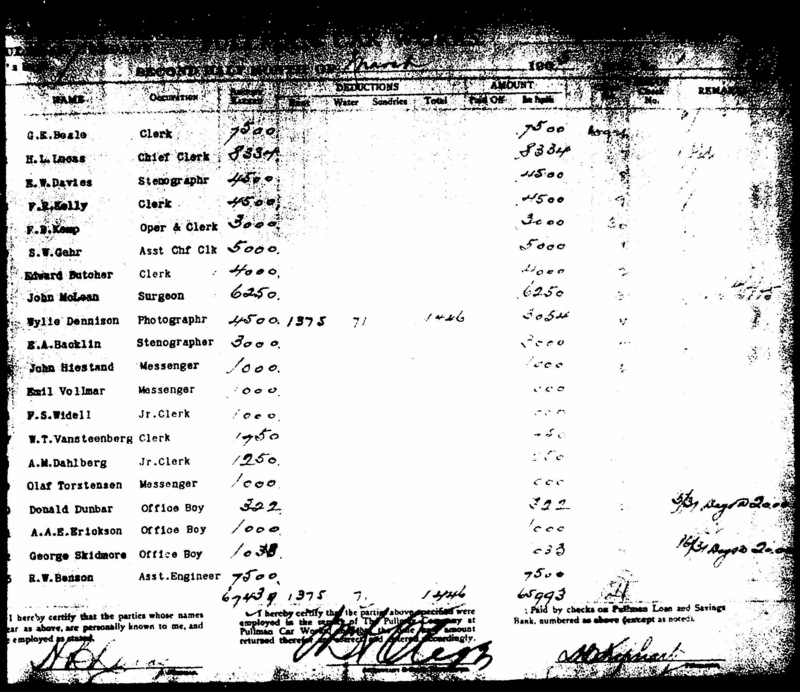

While the Pullman Company developed its Employee Representation Plan for its shop floors and fought the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters on its trains, the Pullman community continued to develop as an important neighborhood on Chicago’s south side. Families continued to live in Pullman’s homes, worked in Pullman’s factories, and attended Pullman’s Public School. The company, however, no longer owned many of these spaces. Beginning in 1907, the Pullman Company began to sell of all of its residential and commerical property in compliance with the Illinois Supreme Court’s 1897 ruling. A town that was once George Pullman’s became a neighborhood of Chicagoans.

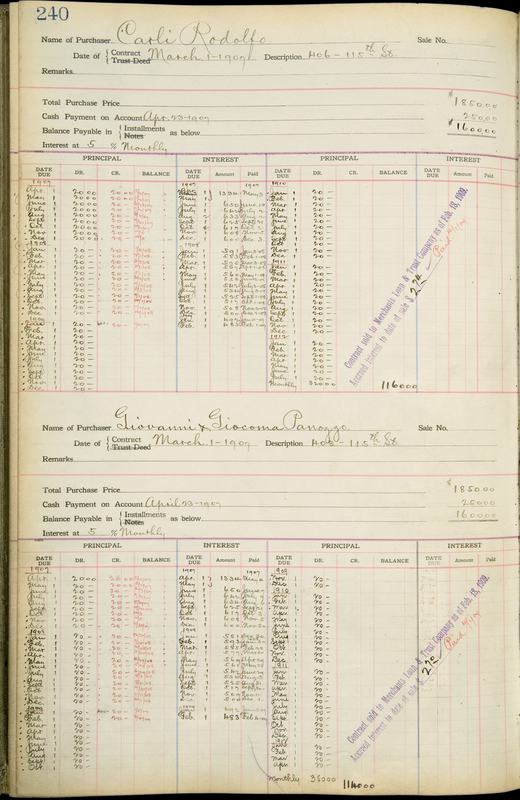

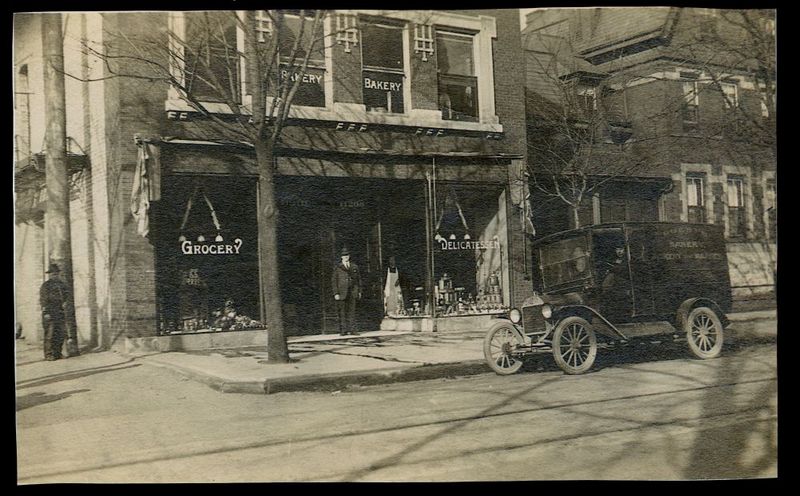

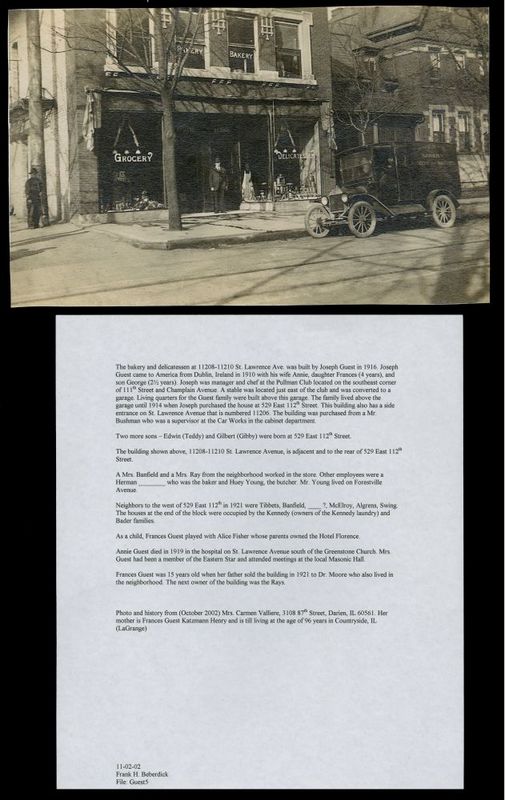

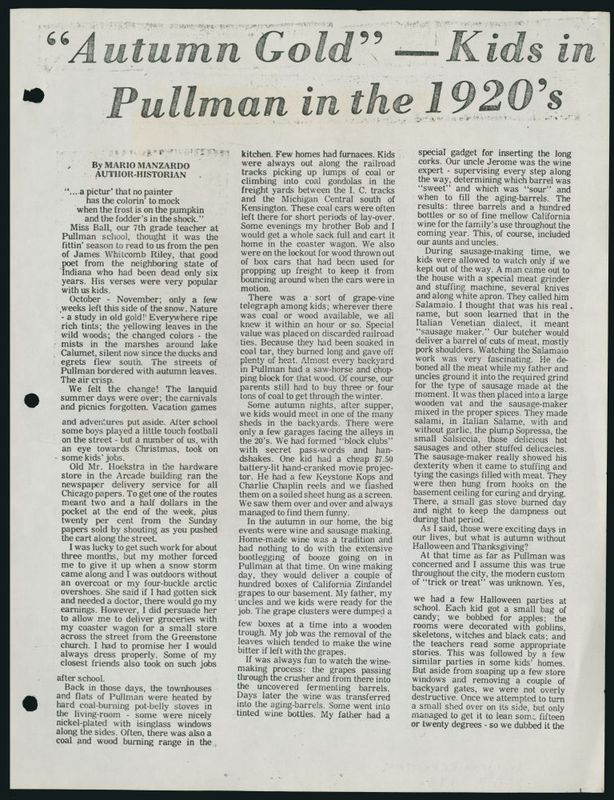

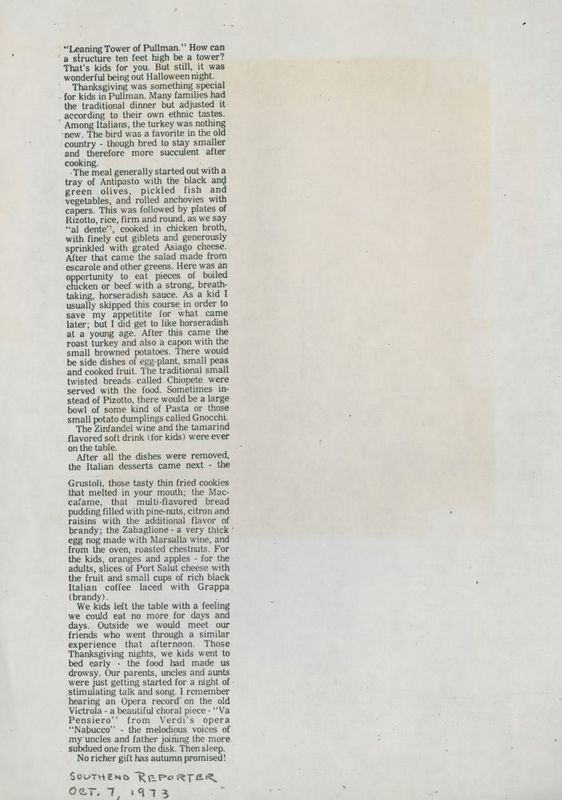

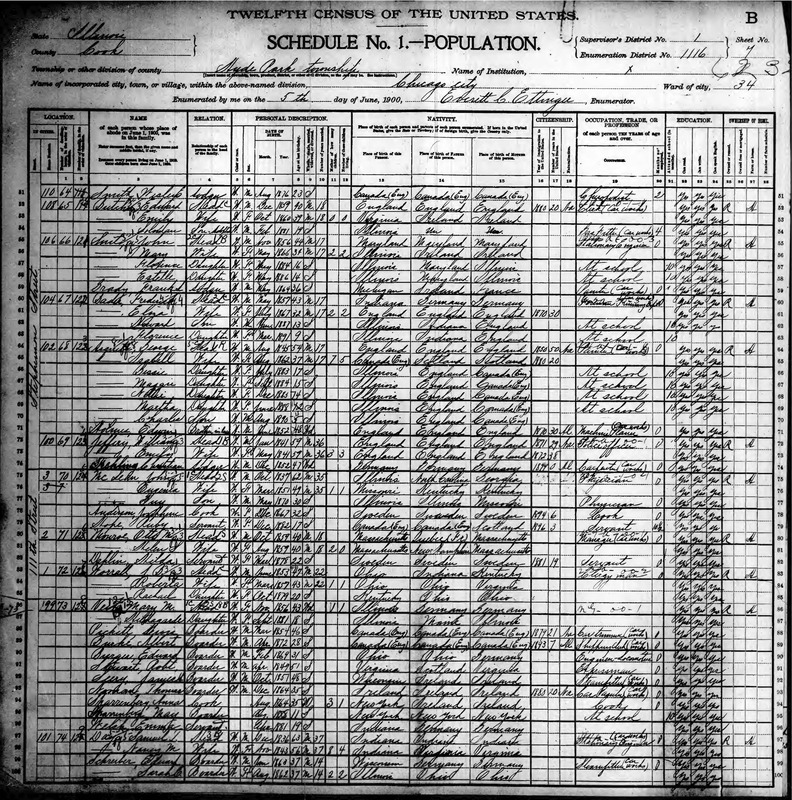

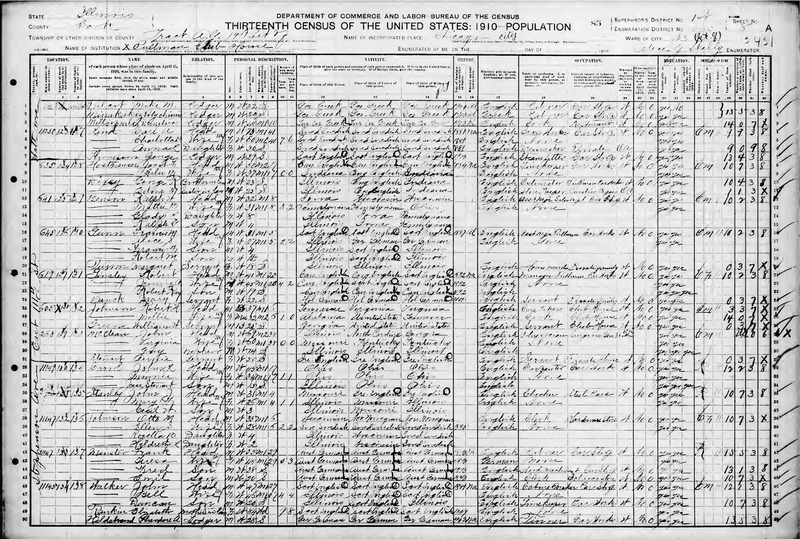

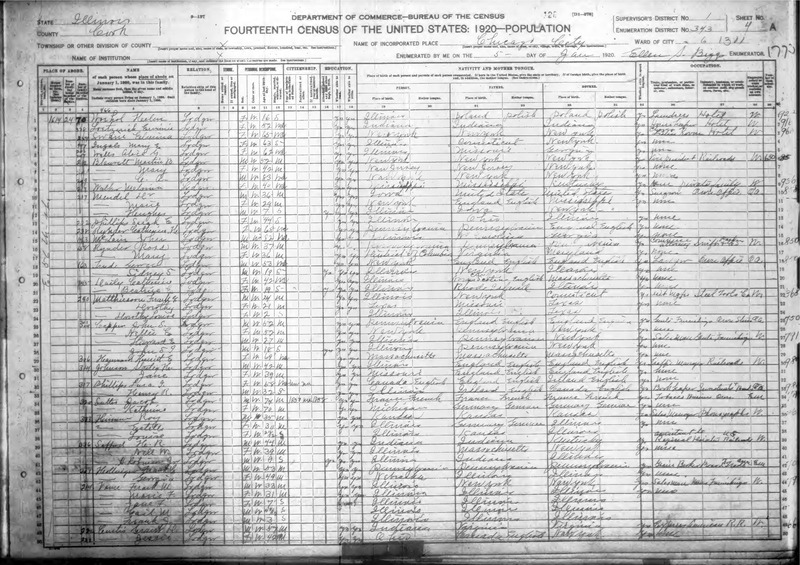

This change in ownership was accompanied by a far more profound demographic transformation of the Pullman community. Upon the town’s founding in 1880, Pullman cars were almost universally constructed out of wood. The material required highly skilled workers to utilize and contributed to the employment of native born and northern European immigrants at the turn of the century. At the same time the Pullman Company began to sell off its non-industrial holdings in 1910, however, it also began to switch to mass producing its sleeping cars out of prefabricated steel. The new cars required far less skill to produce, which allowed the company to hire cheaper workers with far less manufacturing experience. These new hires not only filled the factory floors, but came to occupy the homes of the surrounding community. Immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe became the area’s most common residents, who purchased many of the area’s homes, shops, and storefronts as they became available.

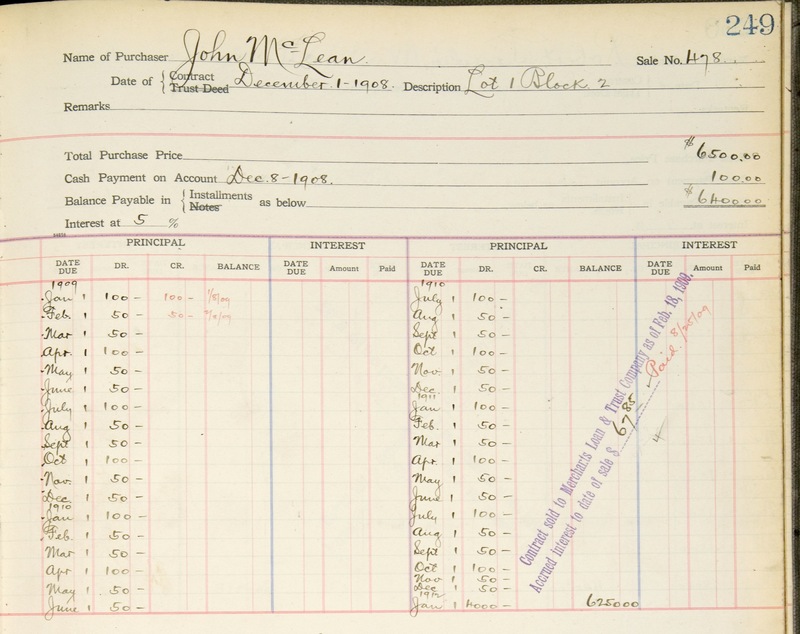

Pullman’s newest residents experienced many of the challenges associated with low paying, unskilled work. Though the company’s real estate records show that individuals purchased Pullman homes, residences in the area often housed three or four families each. Despite these challenges, however, Pullman became a vibrant immigrant community throughout much of the early twentieth century.

A Surgeon's Story

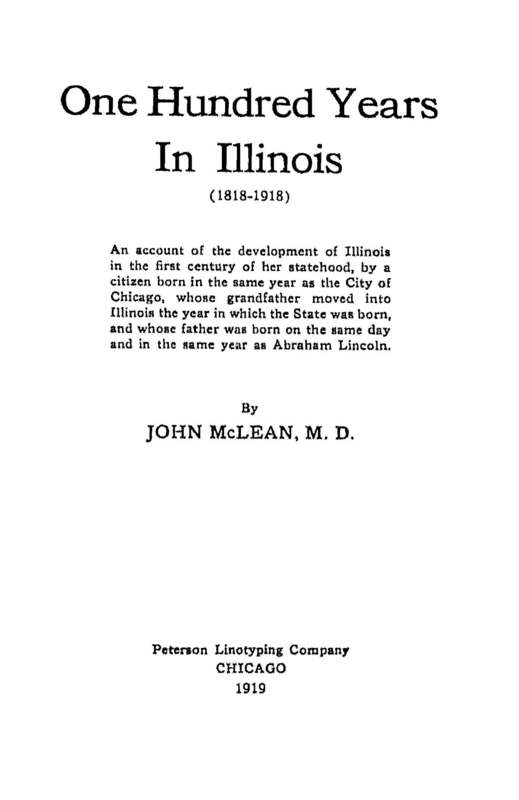

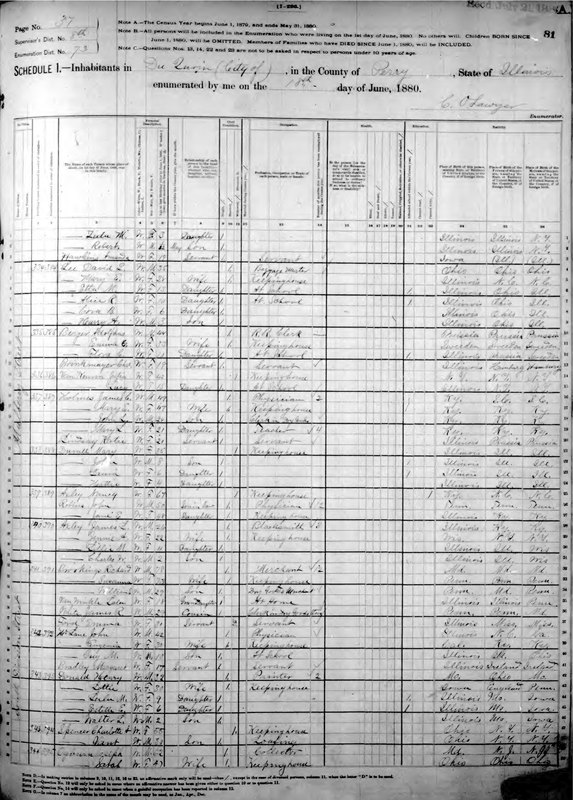

The almost total transformation of the Pullman community in the thirty years after the Pullman Strike is perhaps most clearly revealed in the life of company surgeon John McLean. Employed by Pullman since the late 1880s, McLean elected to stay in the community until he retired. Census records chart the turnover of his neighbors, while McLean’s memoirs provide his personal account of the neighborhood’s transition. Though McLean disparaged these newcomers as foreign invaders who tarnished Pullman’s former “glory,” he astutely observed the changes that surrounded him.

A Deindustrial Community

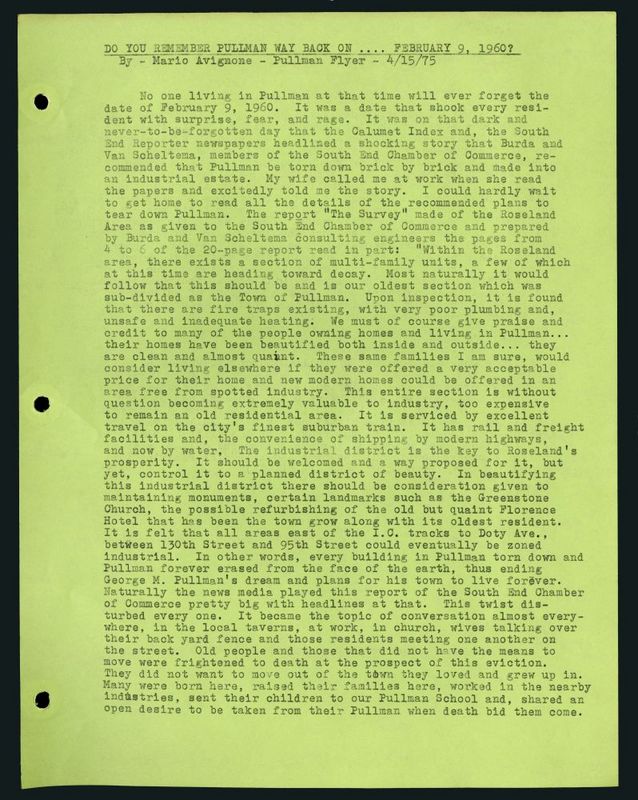

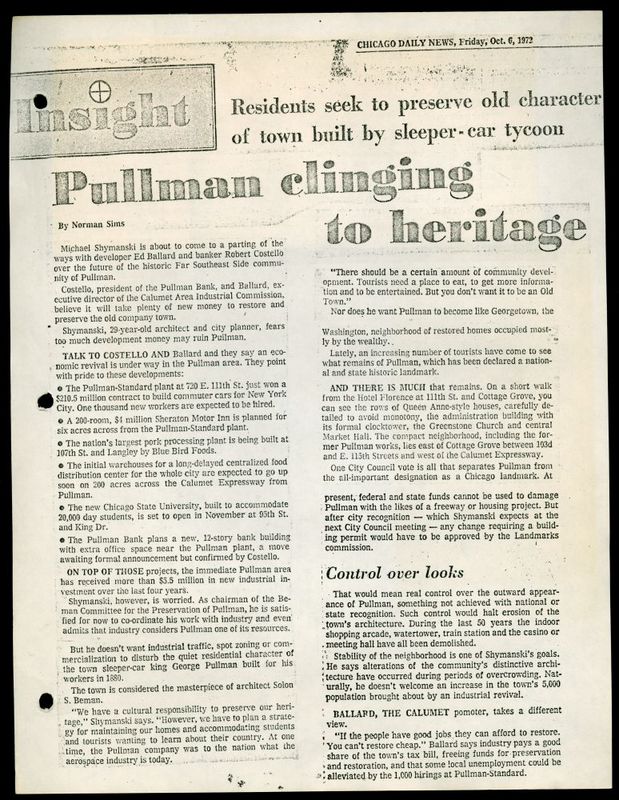

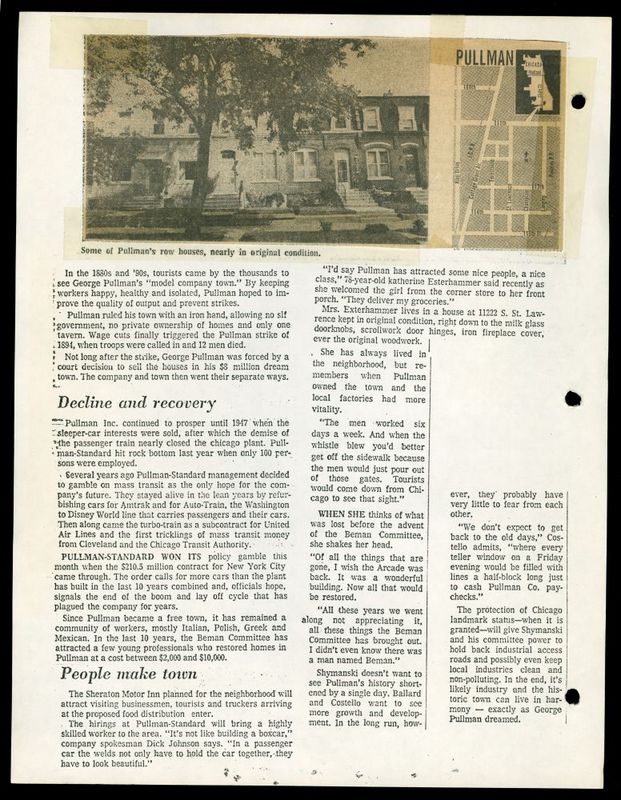

Though McLean derisively interpreted the community’s changing demographics as a decline, Pullman remained a vibrant industrial community of European immigrants and their children throughout much of the twentieth century. The decades following World War II, however, proved far more challenging. The community’s aging housing stock made it a far less desirable place to live, while the influx of African Americans in the nearby Kensington and Roseland neighborhoods led to instances of white flight. Yet it was a decline in the Pullman Company itself that proved the greatest threat. With the steady growth of the automobile as America’s primary mode of transportation, commercial rail traffic declined precipitously. Soon after the war, the company closed all of its shops except for those in Chicago and St. Louis, but even these moves could not offset the shrinking demand for Pullman cars. By 1960, investors considered the community ripe only for demolition and redevelopment. The outcome seemed almost certain when the Pullman Company, the corporate entity that oversaw the operation of Pullman cars, closed in 1969 and the Pullman Car Works, which continued to manufacture railcars for urban transit lines, shuttered its doors in 1981.

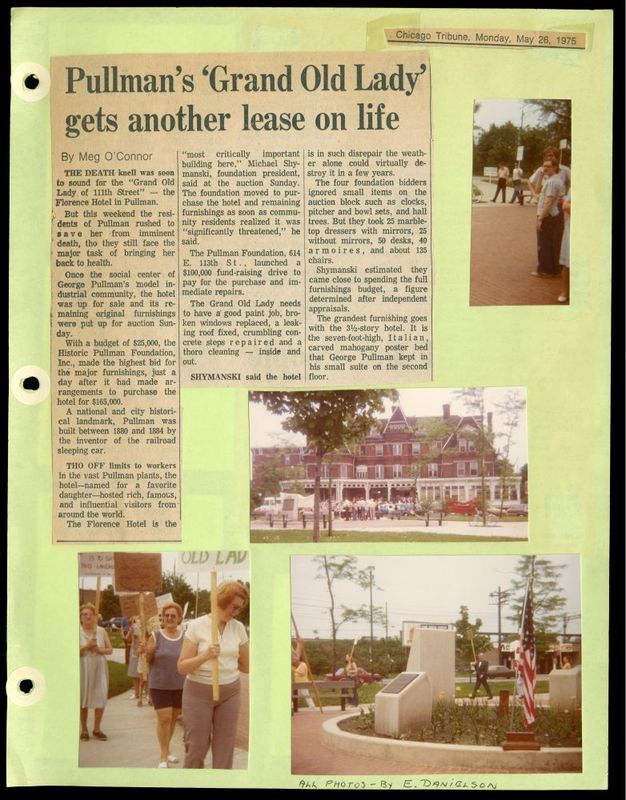

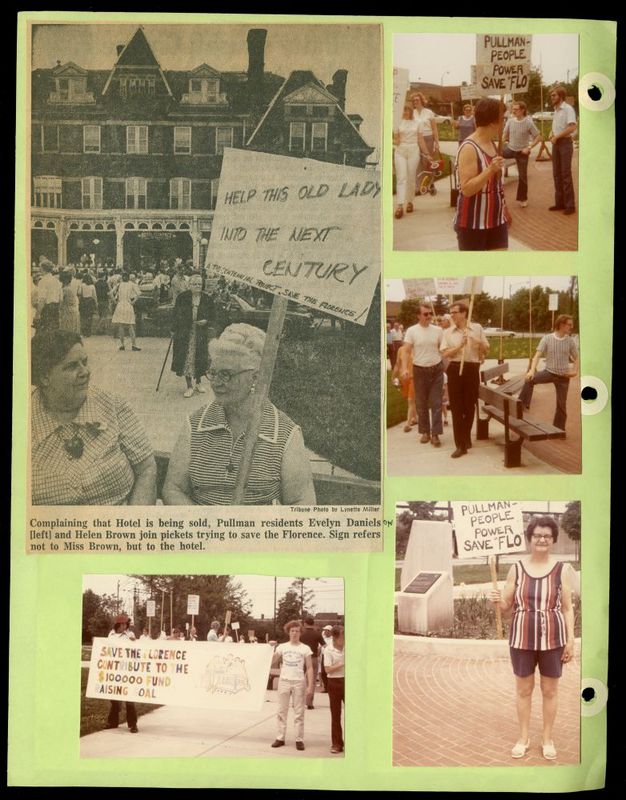

Preserving Pullman

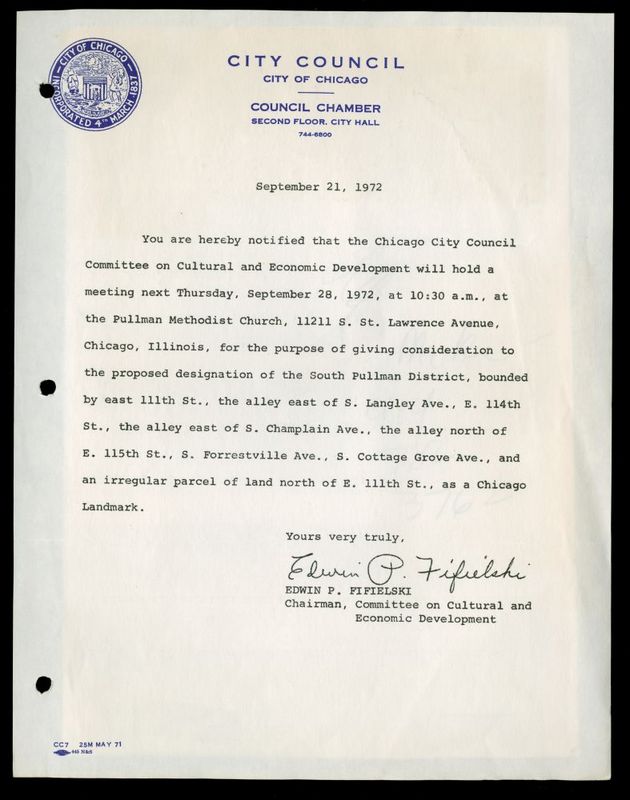

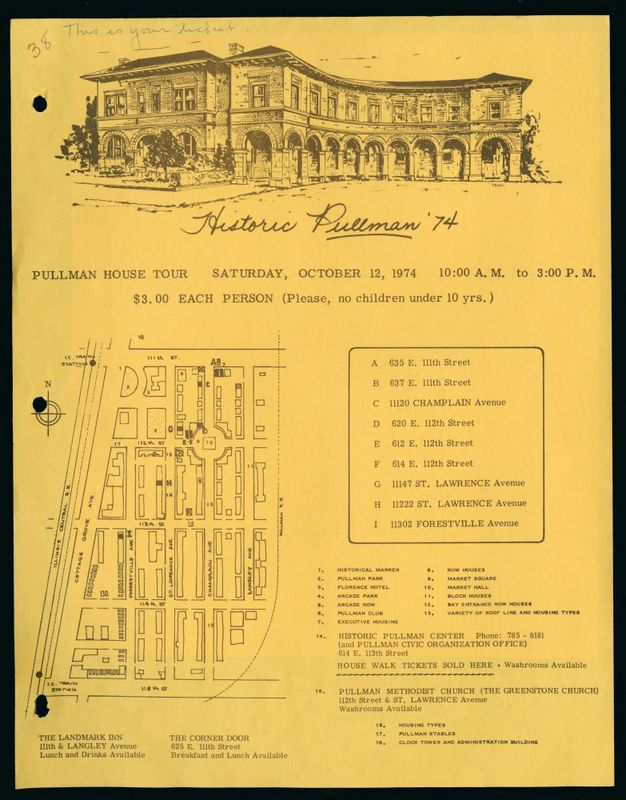

Pullman’s residents did not passively accept the challenges posed to the neighborhood by the company’s closing. Rather, they creatively fought for the community’s future by resurrecting Pullman’s past. As early as 1960, local residents argued that Pullman’s significance as an industrial experiment entitled it to certain protections as a historic site. In 1971 the Pullman Civic Organization, a neighborhood club once charged only with advocating for greater city services, successfully petitioned to have Pullman designated as a National Historic Landmark. The recognition not only safeguarded the neighborhood from destruction, but also made funds available for renovation and preservation. Three years later, residents organized the Historic Pullman Foundation to help expand the community’s access to these resources and continue to advocate for the community’s preservation to this day. After arson destroyed nearly all of the original factory buildings in 1998, the community’s designation as a state historic landmark made funds available to rebuild the old administration building. As of 2012, the area’s renown as a historic site has poised the community for redevelopment.

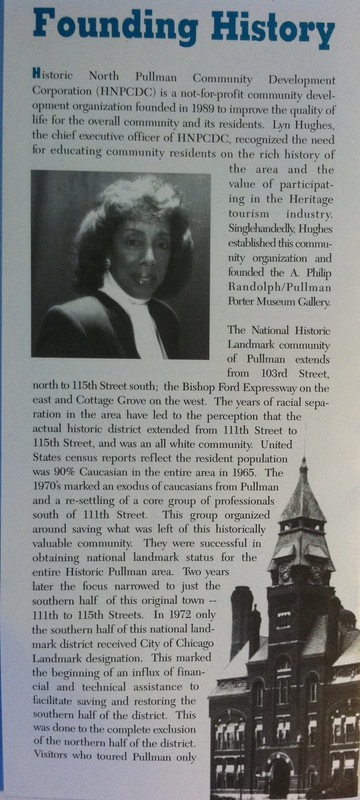

In many respects, this engagement with the past to advocate for the community’s future has become Pullman’s most defining feature. The power of the Pullman Company’s history in relation to the town it once owned not only helped the largely white residents who long occupied the town, but has also become a resource for a residents long kept out of Pullman proper, African Americans. In 1994 residents of the largely African American North Pullman neighborhood, an area that was less developed by the Company and therefore not included as part of the historic district, also petitioned the city for landmark status. Out of these efforts emerged the A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum, which successfully secured a city landmark status alongside the factories and company houses. Though most porters never lived in Pullman, nor even in Chicago, the decision to draw upon the company’s image and history underscores the enduring centrality of Pullman in the history of American race, labor, and urban development.