In the Shops

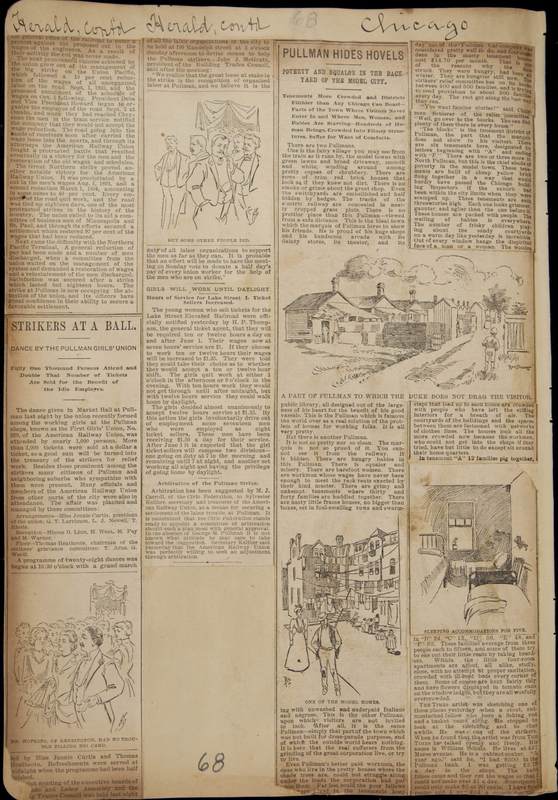

Paternalistic Paradise

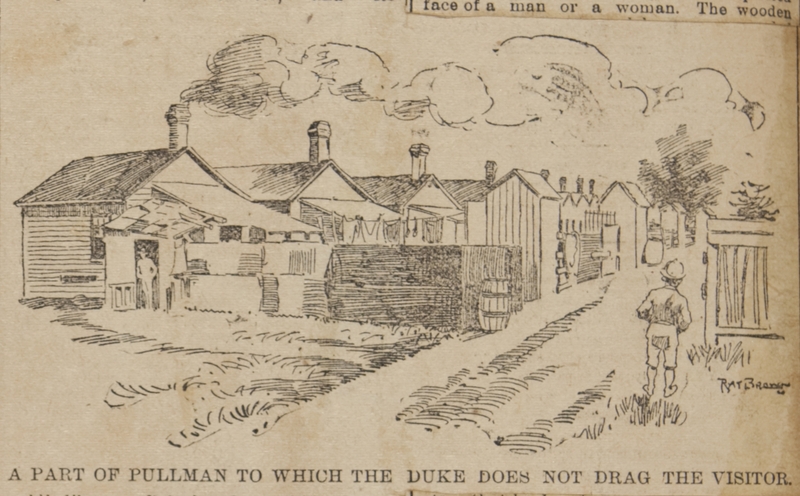

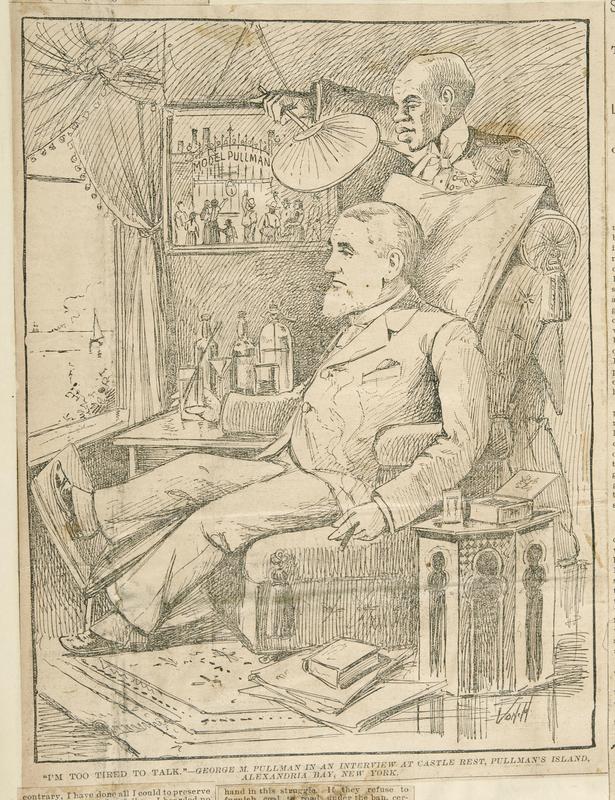

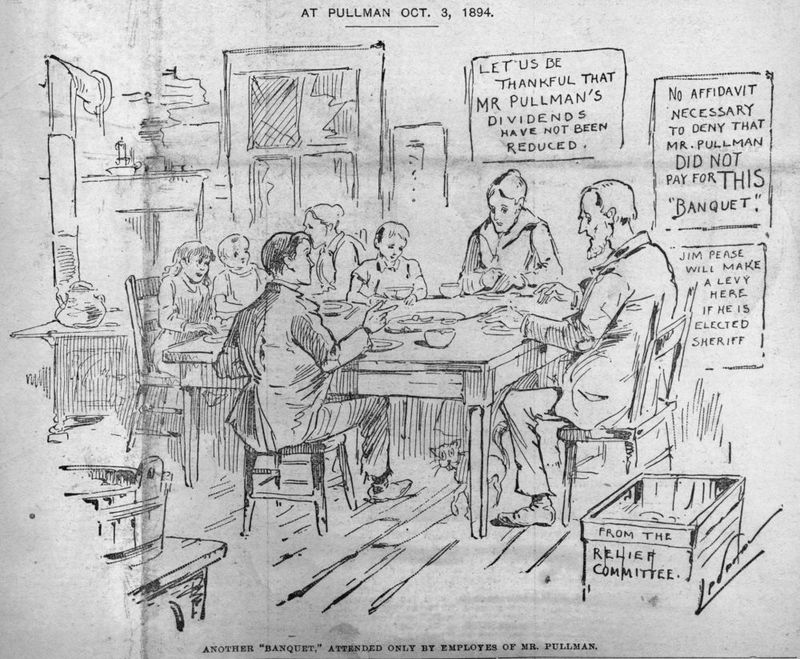

While nearly every observer agreed the town of Pullman represented an experiment in alleviating the conflicts of industrial life, not everyone agreed with Pullman’s solutions. Indeed, from their earliest days, Pullman’s factories were engulfed by many of the conflicts the town was intended to avoid, including the Eight Hour Movement of 1886. Workers continued sporadically to protest the company’s long hours and poor wages throughout the 1880s, but at the start of the 1890s there was a growing number of journalists and observers who also scoffed at the Pullman experiment. The documents collected here reflect this growing critique. All of them marvel at the Pullman experiment. Many, however, also suggested that buried within this model town are the seeds of its own undoing. Some decried the opulence of George Pullman’s standard of living in comparison to even the nicest Pullman home, while others criticized Pullman’s attempt to control every aspect of his workers’ lives. Some, including a growing number of Pullman workers, claimed George Pullman’s experiment was a quest for larger profits, not greater harmony. Changing economic conditions would soon put many of these theories to the test.

Many Suffer Want

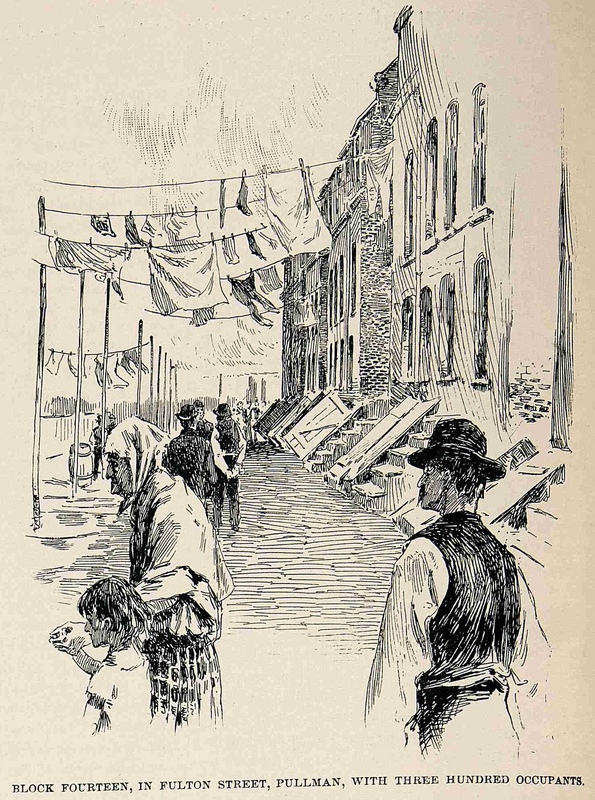

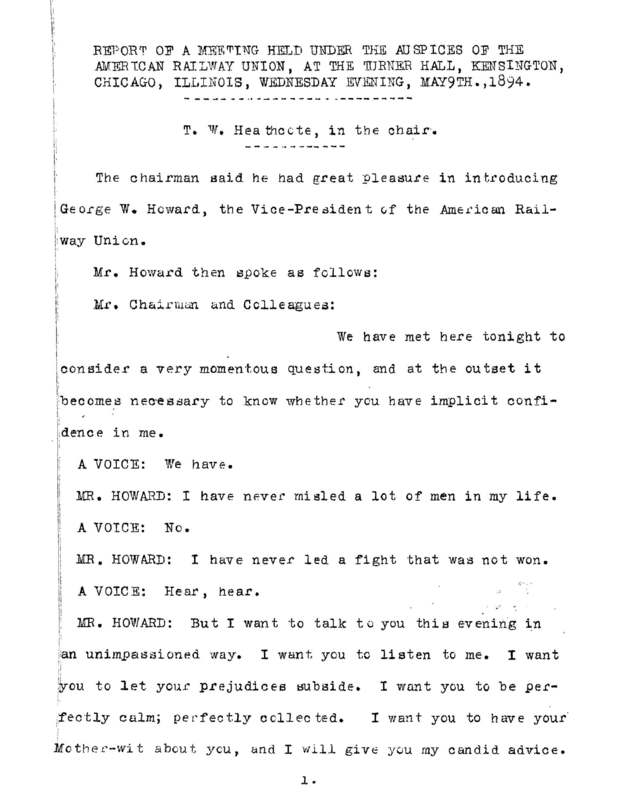

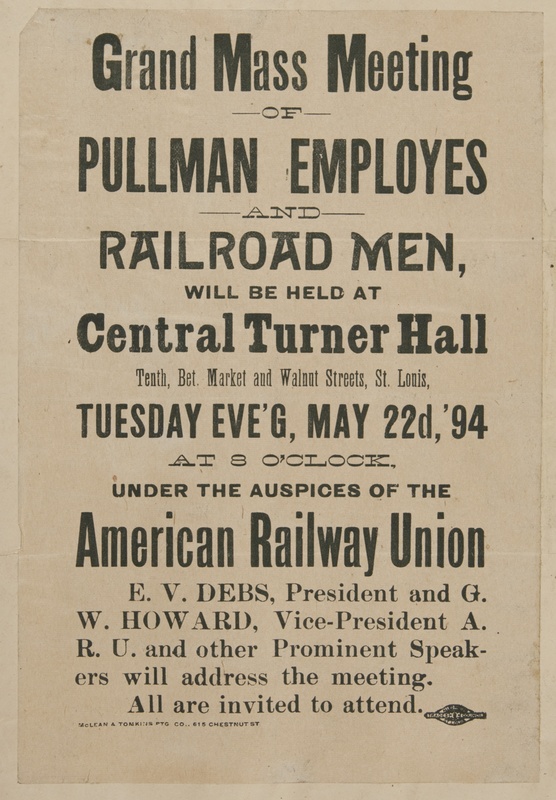

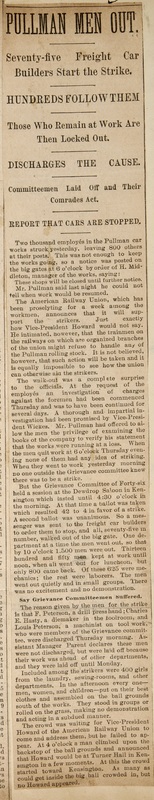

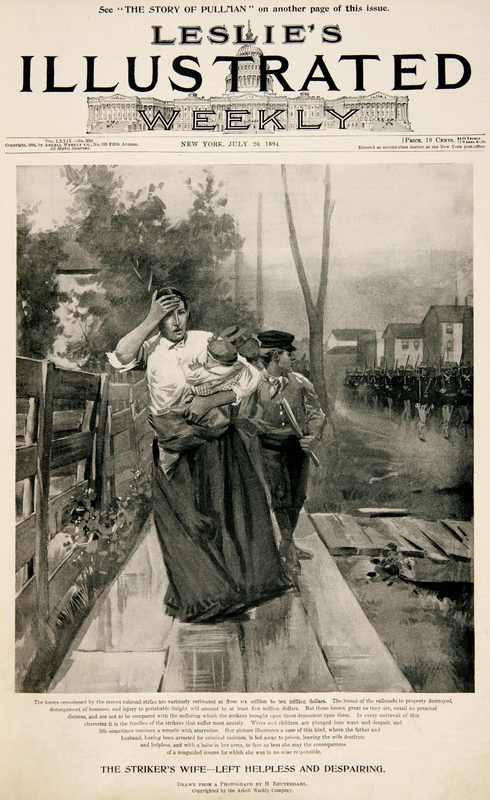

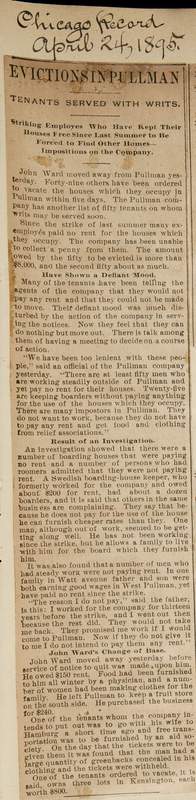

In the decade that followed the town’s founding in 1880, many of the criticisms levied at the Pullman experiment largely came from journalists and activists. As the town entered its second decade of existence, however, an increasing number of Pullman workers became critical of the Pullman Palace Car Company’s competing municipal and industrial policies. With the onset of a nation-wide depression in 1893, many Pullman workers saw their wages severely reduced. At the same time, the Pullman Company kept the rent on the houses it owned and prices on the goods it sold at a constant. In response, Pullman workers for the first time began to organize a labor union. Most joined with the American Railway Union (ARU), a new labor organization founded by Eugene V. Debs. Unlike earlier railroad unions, which were divided by the different types of jobs one did, the ARU allowed nearly any worker engaged in almost any kind of railroad work to join. The object was to empower workers of each individual railroad with the support of workers from other companies. Emboldened by this new support, and increasingly desperate during the depression, a committee of Pullman workers went before the company’s management to negotiate a restoration of wages on May 9, 1894. Managers refused to negotiate with the workers, and the next day fired three members of the committee. In response, three thousand Pullman workers walked off their jobs in protest on May 11. The Pullman Strike had begun.

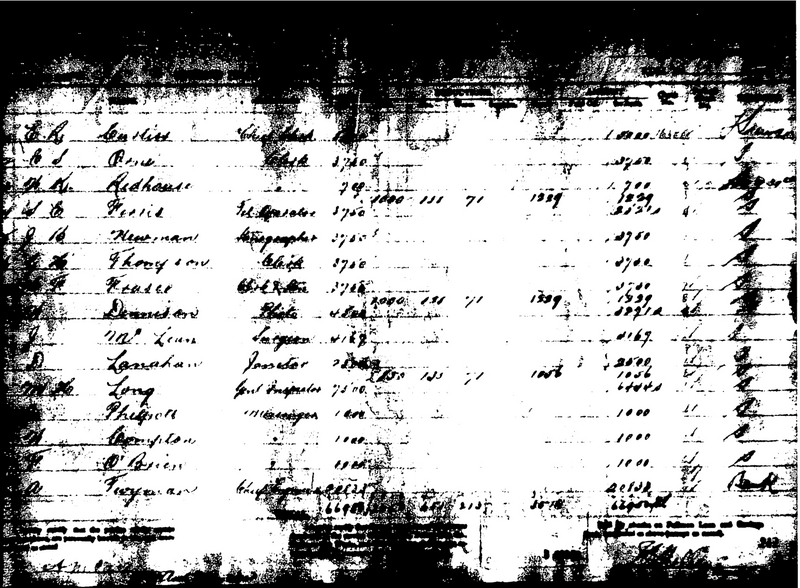

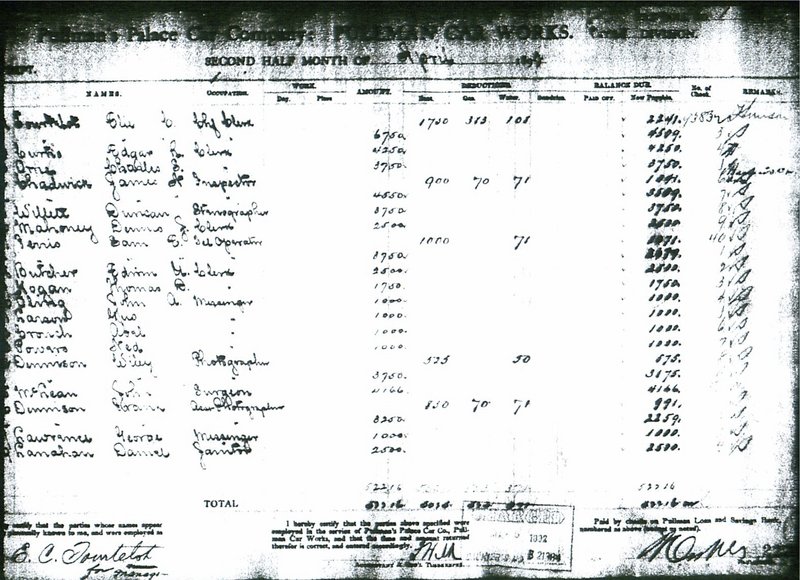

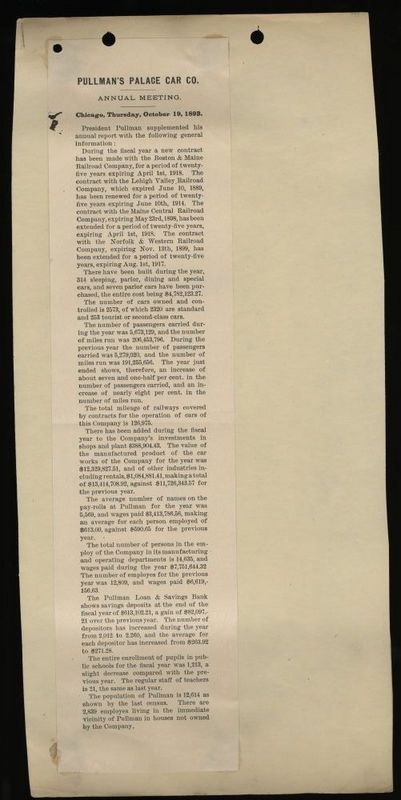

The documents that follow provide a glimpse of the conditions workers faced heading into the strike, as well as the Pullman workers’ organizing efforts. The payroll records and corporate statements from 1893 and 1894 convey just how precipitously workers’ wages declined in relation to the Pullman Company’s growing profits. Material from the ARU, meanwhile, shows the centrality of Pullman’s model town ideal to the organization of the union. One worker’s twelve-cent paycheck became a rallying cry against the company, while union leader Thomas W. Heathcoate emphasized the company’s ownership as a form of despotism in his speeches before the ARU.

The Strike

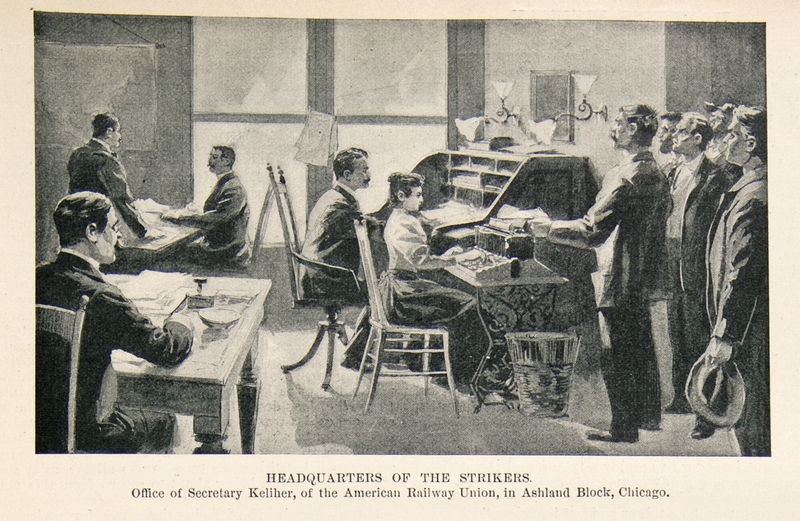

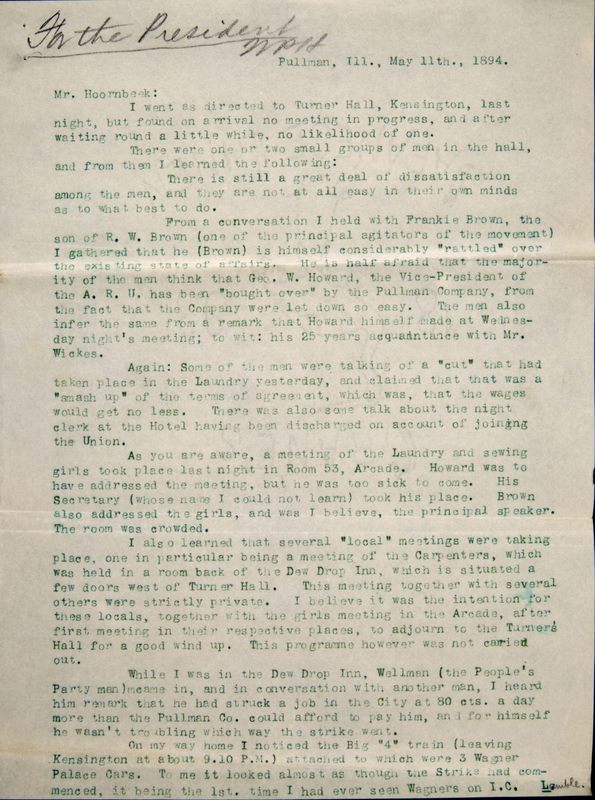

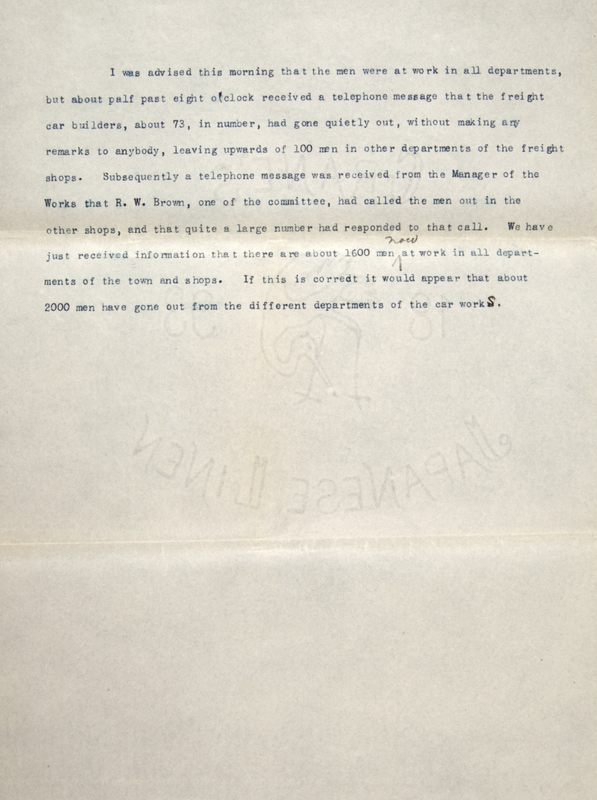

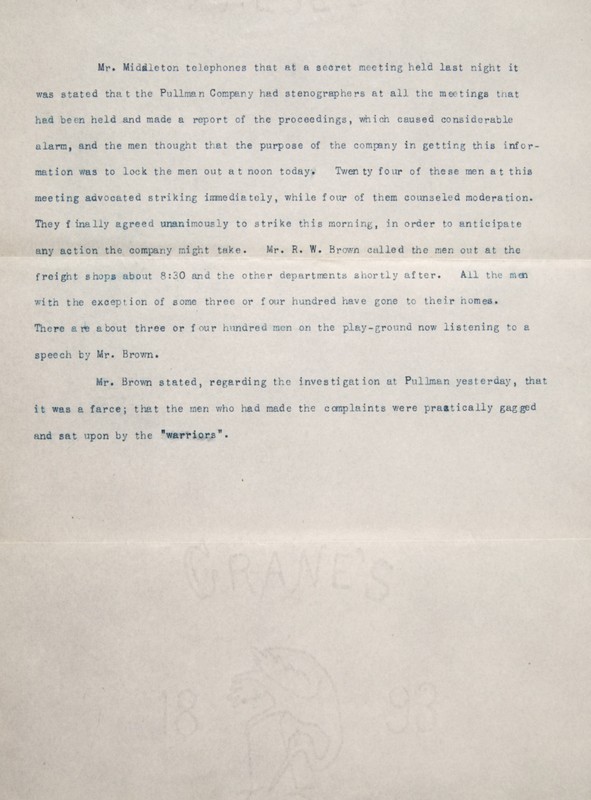

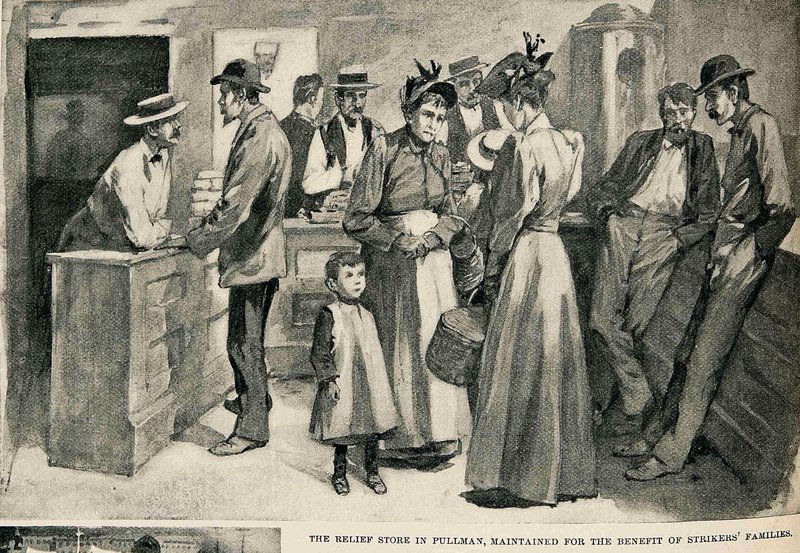

Over the next month, the Pullman Strike proceeded peacefully as a war of attrition. Under the leadership of Vice President T. H. Wickes, the Pullman Company responded to the walkout by closing all its factories in the town. The company hoped to wait out the strike, knowing the economic depression would make it difficult for workers to find temporary employment. The company’s internal memos provide an unprecedented glimpse into these efforts. The American Railway Union, meanwhile, began to organize supplies to support their now unemployed members in Pullman. In a clear sign of the rift between the company and its workers, the ARU established its headquarters in a hall in the adjacent neighborhood of Kensington. The strikers were already very familiar with the area, for many frequented Kensington’s saloons to circumvent Pullman’s selective prohibition of alcohol.

The Boycott

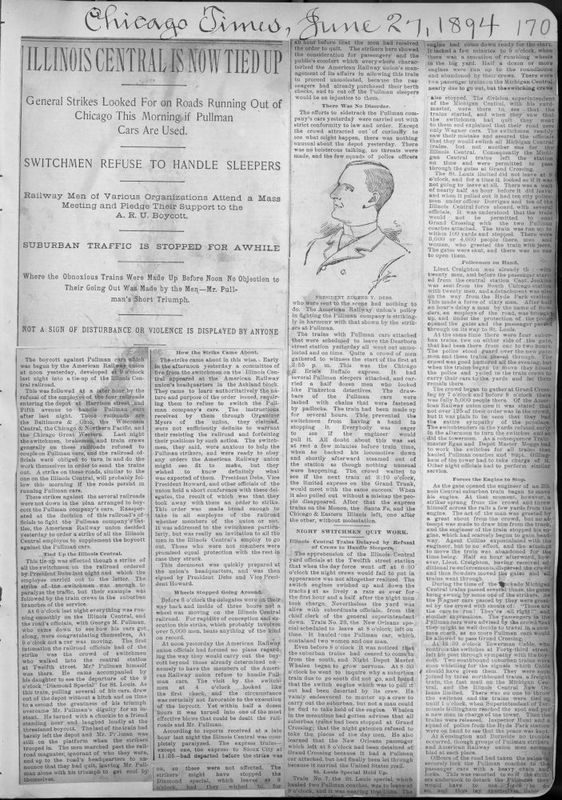

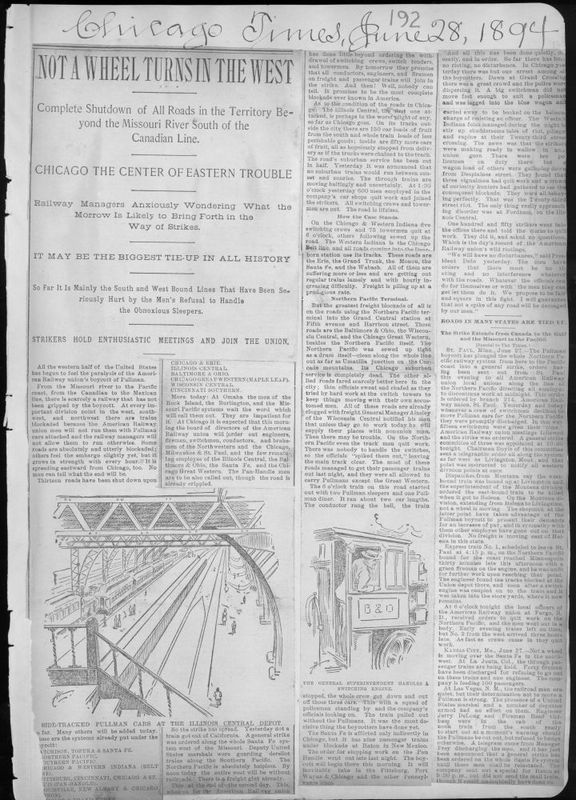

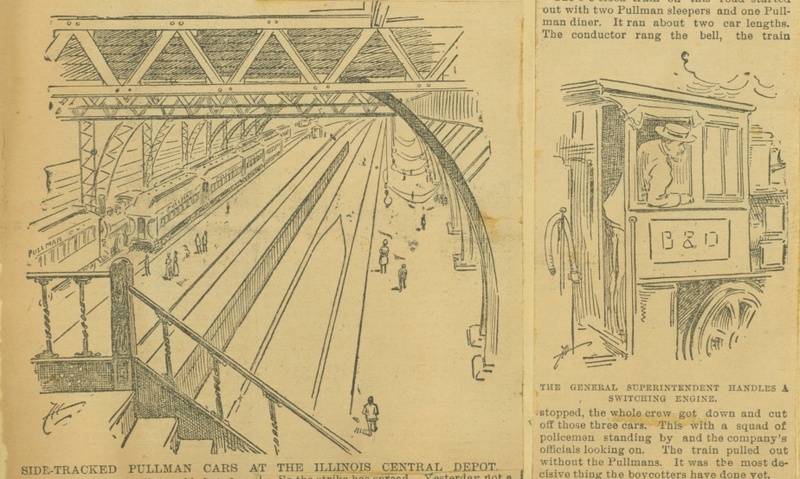

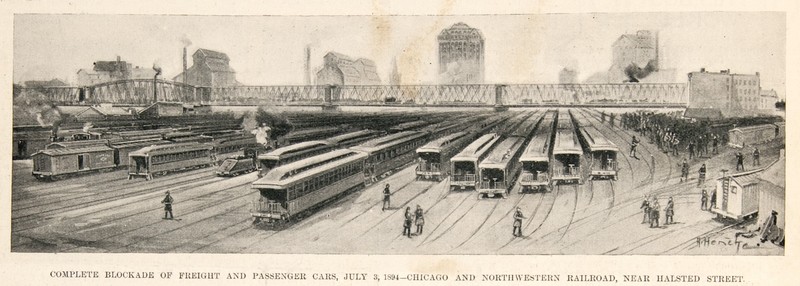

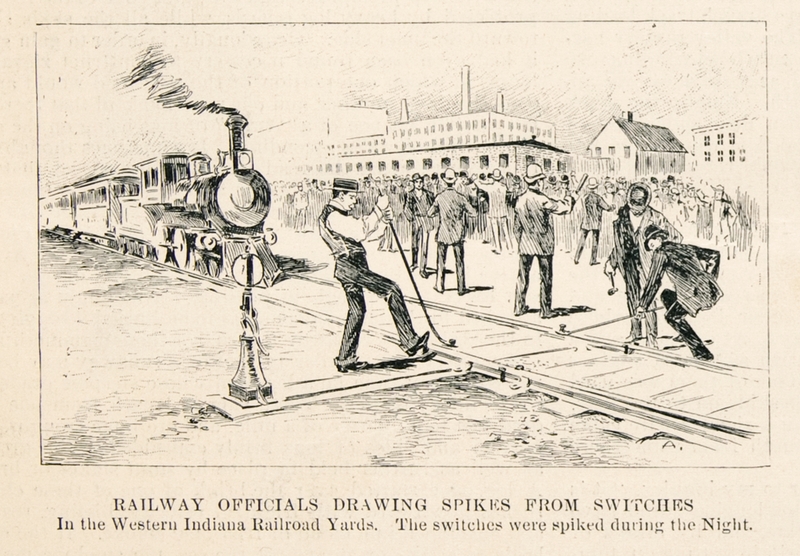

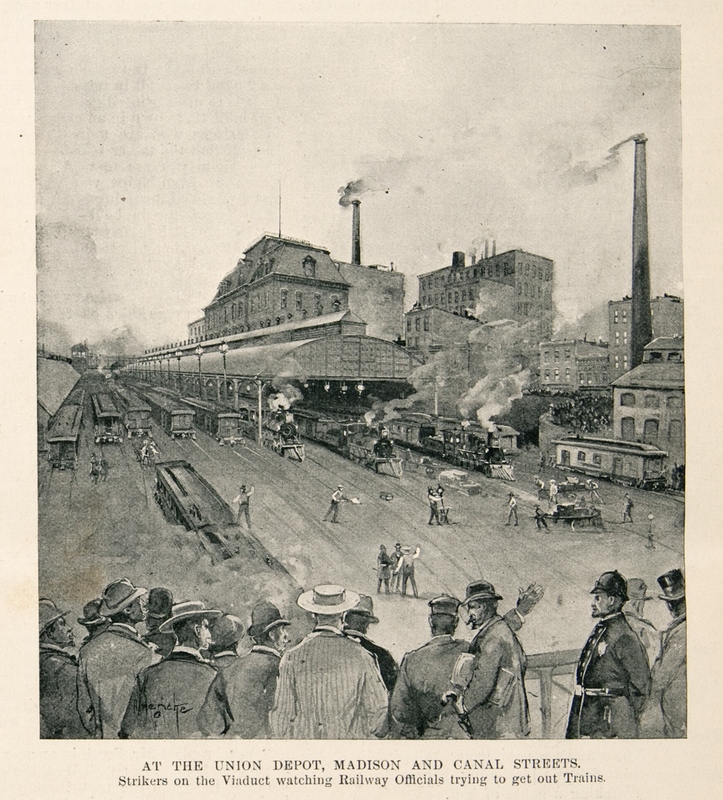

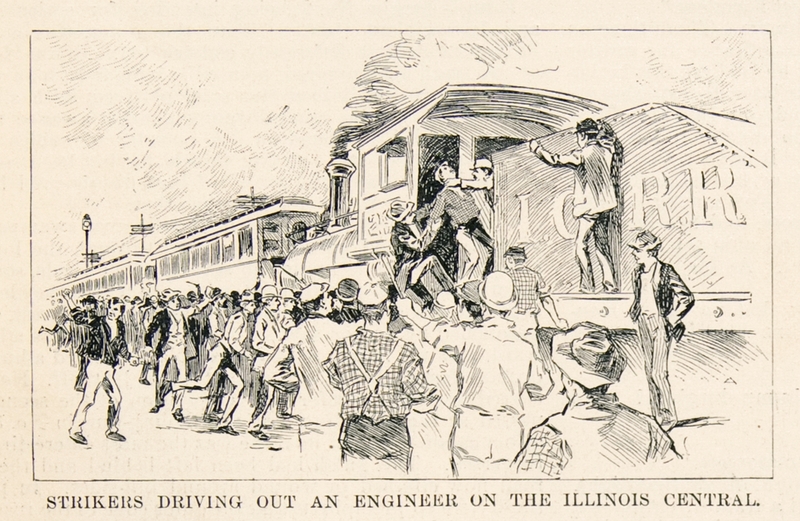

By the second week of June, the strike stood at a standstill. The strikers continued to demand the right to negotiate their wages, while the company refused to negotiate with either its workers or the American Railway Union. George Pullman had even fled his Prairie Avenue home in Chicago for a fortress-like mansion he had built on an island on the St. Lawrence River. A growing number of members within the ARU therefore thought greater action was needed. On June 12, 1894, delegates from across the country representing nearly a 150,000 railroad workers convened in Chicago to determine their next steps. On June 22, the Union announced that if the Pullman Company did not agree to address its workers’ grievances by June 26, ARU members would refuse to work trains carrying Pullman cars. After the company refused to comply with the union’s ultimatum, the Pullman Strike expanded to become a far more expansive boycott of Pullman Sleeping Cars. In support of the Pullman strikers, railroad workers across the country uncoupled Pullman cars from trains or refused to operate trains carrying them, virtually shutting down traffic west of Chicago. At the same time, a growing number of workers in the city, many of whom had also lost their jobs or had seen their wages slashed, also began to protest the Pullman Company in sympathy with the town’s workers.

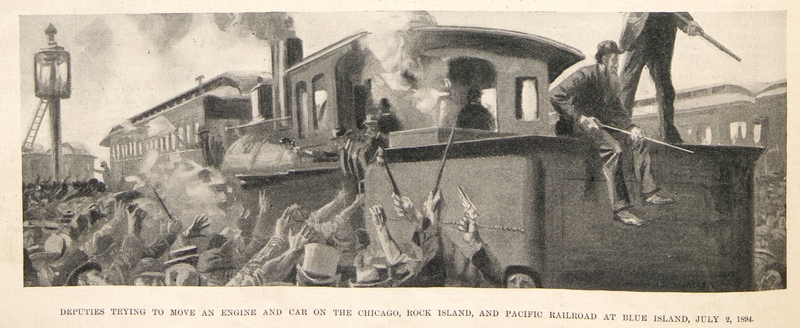

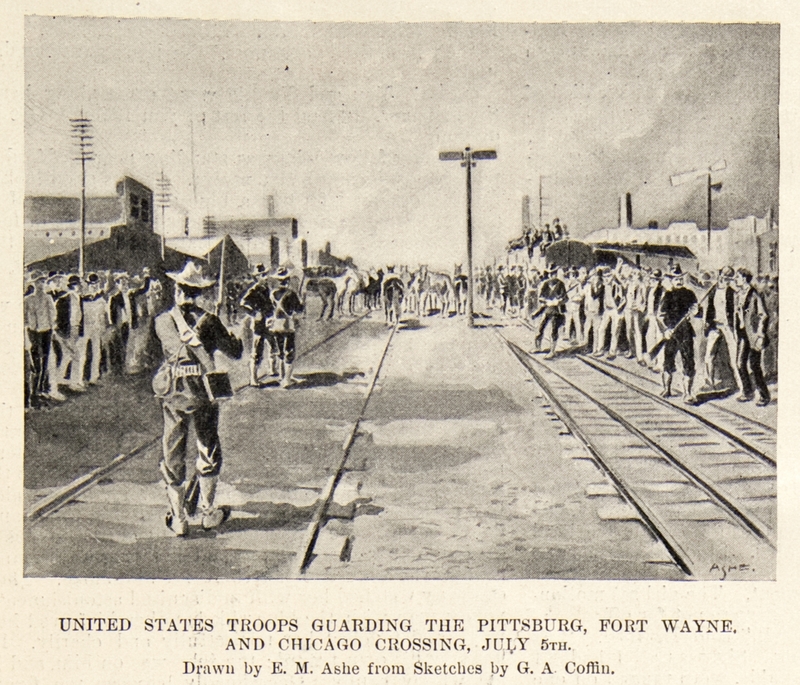

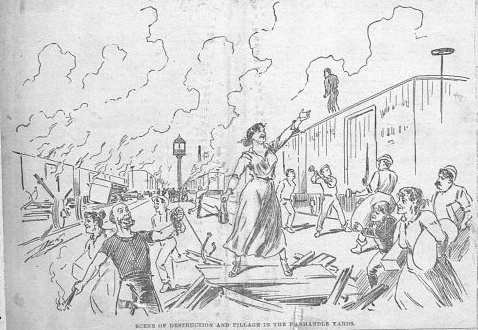

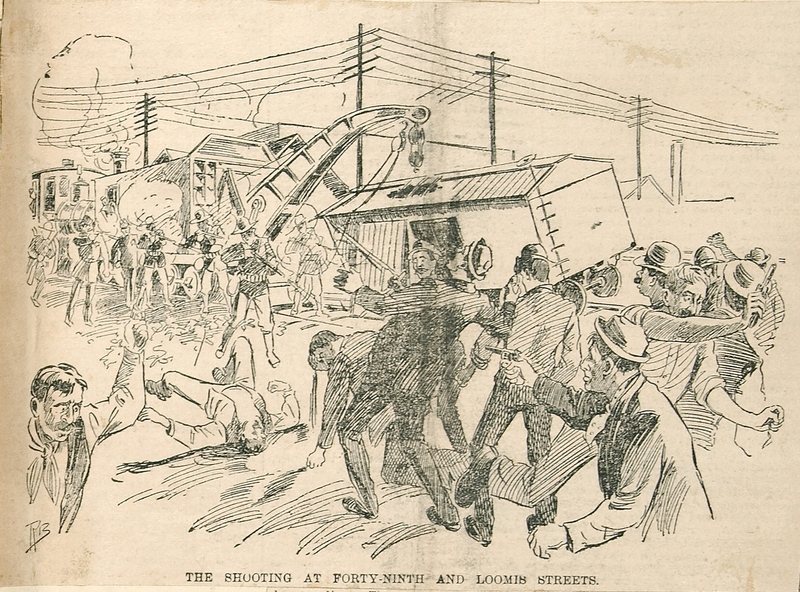

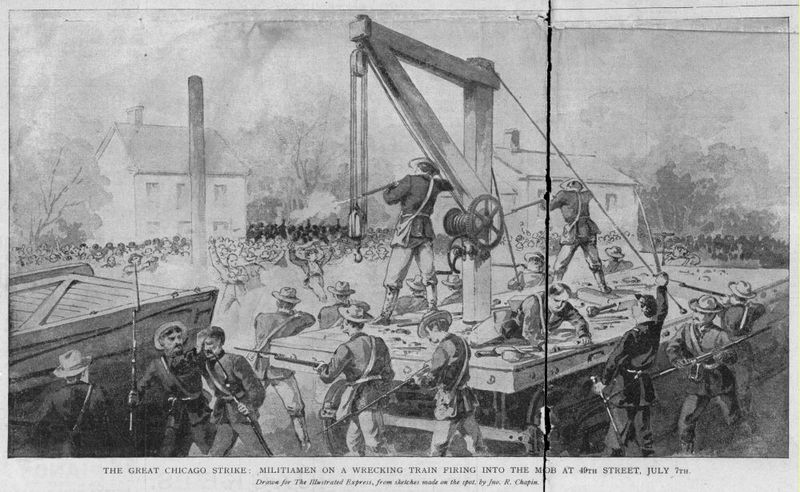

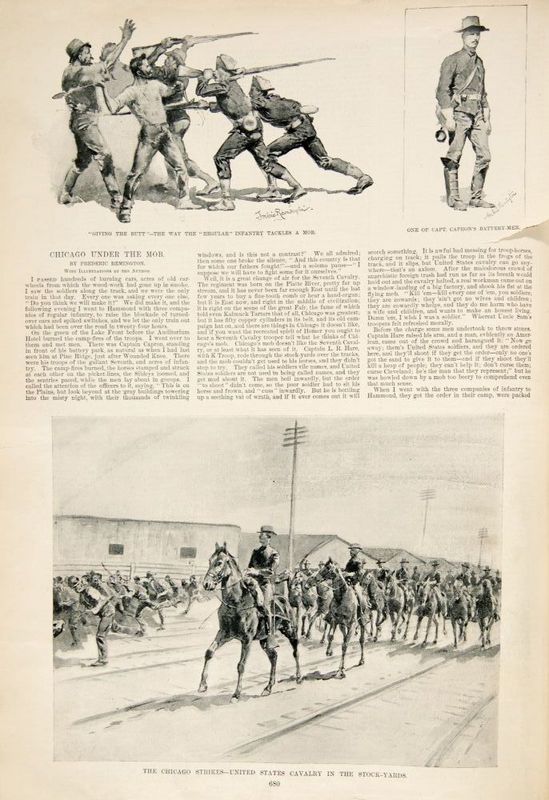

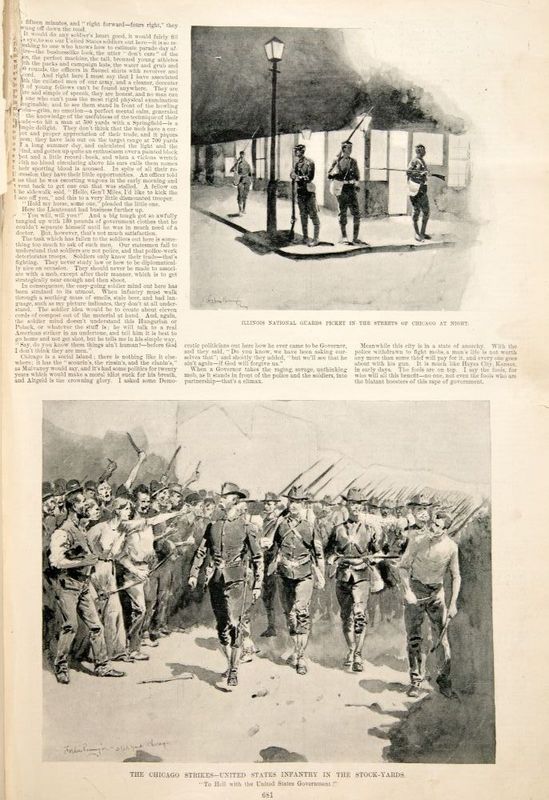

The documents here cover this shift from the Pullman Strike to the Pullman Boycott. The change in the visual imagery as well as the source of the images reflect the strike’s growing notoriety. National publications such as Harper’s Weekly began covering the boycott, and their illustrations reflect popular views of labor protests. In place of the printed demands and sketches of strike headquarters, illustrators emphasized the supposedly violent, chaotic efforts by workers to stall railroad traffic.

Chicago Under the Law

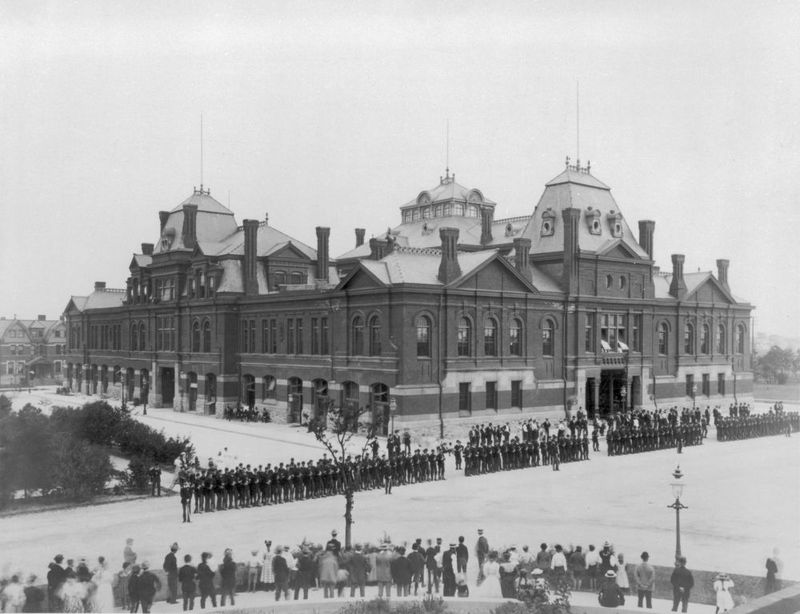

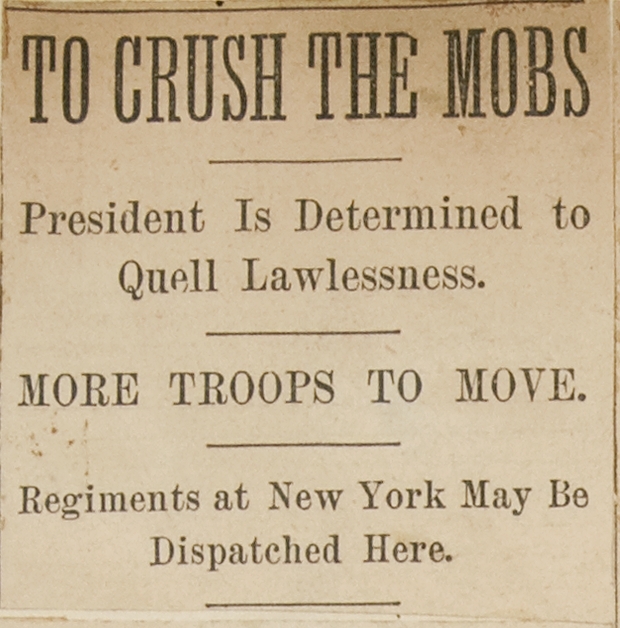

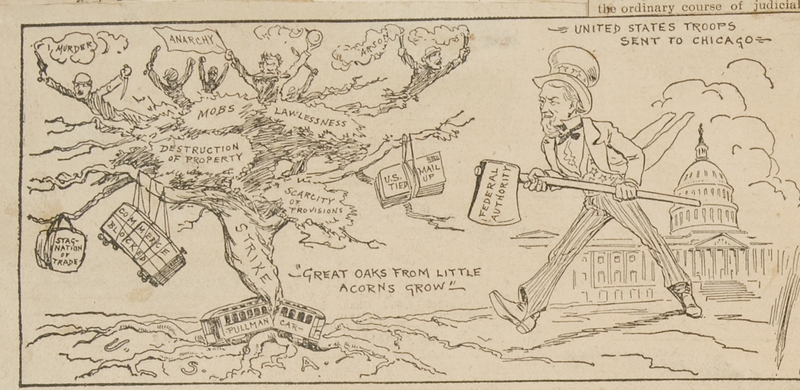

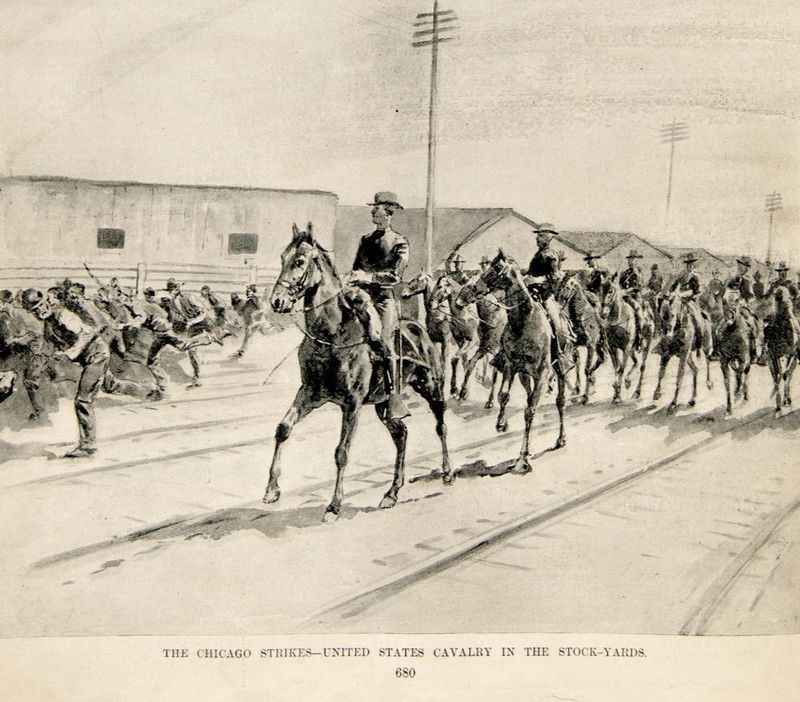

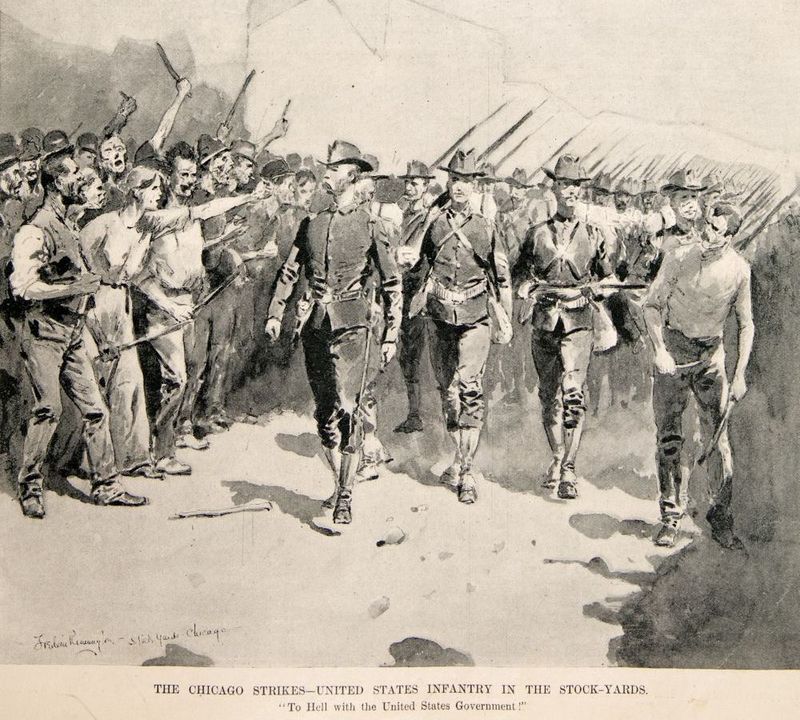

In Chicago, attempts to block Pullman cars from leaving their stations became increasingly aggressive. On June 29, 1894, a number of railroad workers in Blue Island, Illinois, tore trains from their rails and set fire to a number of railcars following a peaceful rally led by Debs. The action was exactly what the Pullman Company had hoped for. Since June 22, Pullman Company executives had been meeting with several other railroad secretaries in what they called the General Managers Association (GMA). The GMA aimed to collaborate and share resources not only to prevent the spread of the Pullman boycott in particular, but also to break the American Railway Union. After the actions in Blue Island, the Association succeeded in having a special prosecutor appointed to handle the strike. Just two days later on July 2, Attorney General Richard J. Olney, who until 1893 was a lawyer for a large railroad in the General Managers Association, obtained an injunction that ordered the ARU to end its boycott. A court order that could lead to jail time if it was broken, the injunction forbade ARU leaders from even suggesting workers refuse to operate trains carrying Pullman cars. It was the first time such a measure had been used to suppress a labor conflict. When workers refused to return to work or allow trains carrying Pullman cars to pass, President Grover Cleveland dispatched 10,000 federal troops to protect railroad property in Chicago and cities throughout the West.

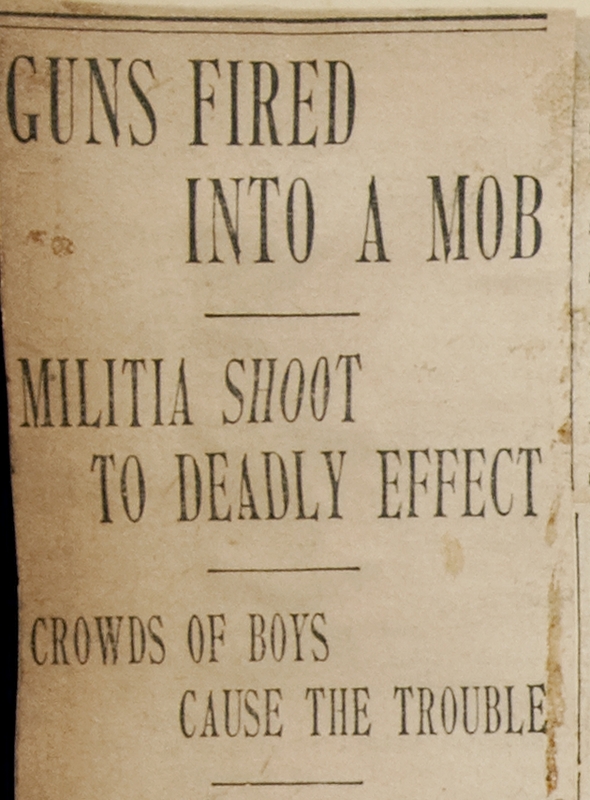

Crack of Rifles

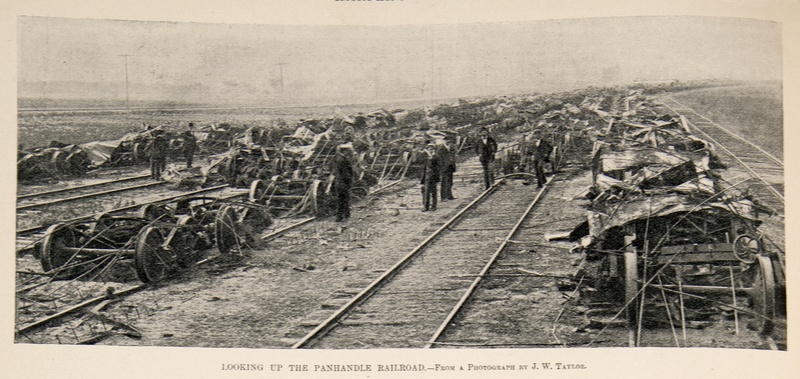

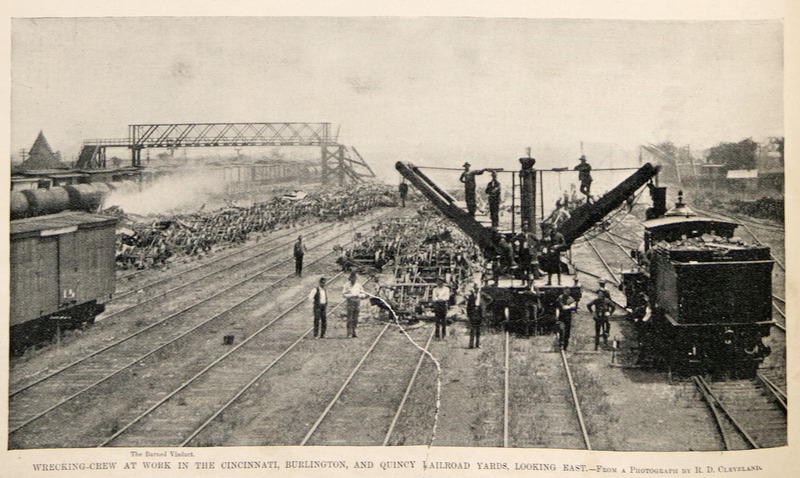

The presence of federal troops in the city seemingly siding with Pullman and the other railroad companies enraged Chicago’s striking workers. Over the next several days, crowds of working people occupied rail yards throughout Chicago. In Kensington workers overturned, derailed, and set fire to parked rail cars, while workers in other parts of the city similarly destroyed railroad property. By the morning of July 7, over $340,000 in railroad property had been destroyed (nearly $8.5 million in 2010 dollars). In response, troops became more aggressive in their attempts to keep the peace. After a crowd of workers barricaded tracks and hurled objects at troops escorting a train through the working-class Back of the Yards neighborhood, the military opened fire on the workers, killing at least a dozen civilians and wounding several more.

The violence that accompanied the federal troops upon their arrival in Chicago became the Pullman Strike’s defining feature. As the photographs and illustrations capture, the skirmishes between strikers and the military and the damage that resulted became the focus of the press. What had begun as a strike of 3,000 Pullman workers demanding wage increases was now portrayed as riotous mobs attempting to destroy railroad companies. The model town of Pullman fell decidedly into the background.

Vanguards of Anarchy

Public opinion quickly turned against the boycott, as the cartoons and illustrations here convey. Though many observers continued to lament George Pullman’s unwillingness to even meet with his workers, most commentators looked upon the boycott as a nuisance and not as a legitimate tactic for working people to compel their employers to negotiate. The town of Pullman, and even most Pullman workers, nearly disappeared from the public discourse.

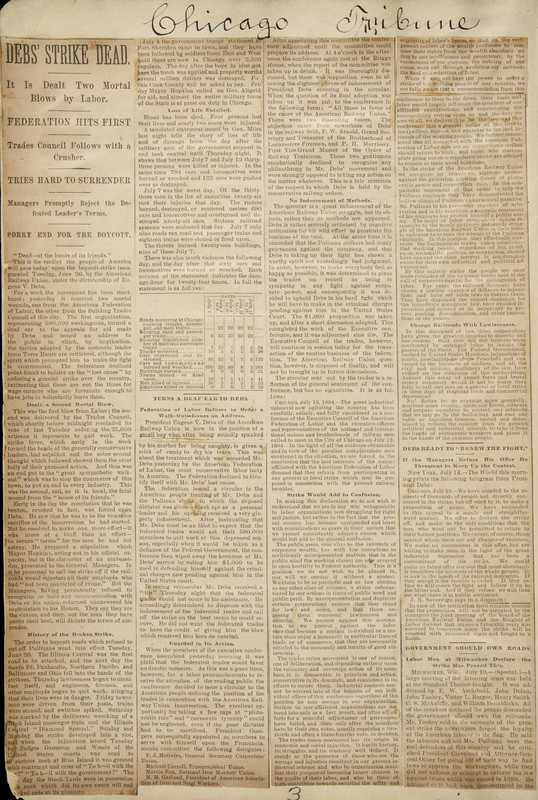

Debs' Strike Dead

Ultimately, however, the shift in public sympathy away from the strikers had little impact on the conclusion of the Pullman strike. The injunction obtained by Attorney General Olney was the deathblow. On July 7, Debs and other ARU leaders were arrested for violating the court order and were eventually sentenced to a six-month prison term. With the ARU leaderless, the boycott began to lose steam and rail traffic slowly returned. By late July, the strike at the factories in Pullman, which had inaugurated the nationwide conflict, also began to wane. On July 20, a first contingent of strikers returned to work. On August 2, the ARU officially ended the boycott and the town of Pullman fully reopened. Most of the union leaders were blacklisted, and wages remained as they had before the strike.

In the months that followed, observers across the country struggled to identify the cause of the Pullman strike. President Grover Cleveland appointed a commission to recommend legislative solutions, while figures such as Jane Addams looked to more cultural causes. Even Eugene Debs reevaluated his understanding of American politics in the wake of the strike. Nearly every observer agreed the Pullman experiment had failed. But they differed as to the sources of the experiment’s failure. The Strike Commission largely laid the blame on the Pullman Company’s overzealous attempts to create harmony through social control. Figures like Debs and Addams, meanwhile, cited the fundamental inequalities of industrial capitalism that allowed a single individual to build and own his own town to begin with. In fact, Debs would eventually arrive at the conclusion that the only way to protect the working public from private industrial was to publicly own industry. In 1901, just five years after his release from prison, Debs helped found the Socialist Party of America, citing the Pullman Strike as the catalyst that pushed him toward socialism.

Parternalism Redux

The nationwide Pullman Strike had a lasting impact on American labor relations. The use of an injunction against the American Railway Union’s sympathy boycott not only destroyed the Union but also became a standard practice to break strikes throughout much of the twentieth century. Yet at the same time, the violence that the strike generated also contributed to a growing sentiment that employers should at least negotiate, if not arbitrate with their employees. For the workers in the town of Pullman, however, the strike had a far more complicated legacy. Workers returned to their jobs with their pay unchanged. Conditions in the community, however, did change. Shortly after the strike’s conclusion, Cook County’s Attorney General filed charges against the Pullman Company claiming that the company’s ownership of residential and commercial property violated its legal incorporation as a Sleeping Car company. The Illinois Supreme Court agreed and in 1898 ordered the company to sell all property not related to railcar production. By that date, George Pullman himself had passed, succombing to a heart attack in 1897.

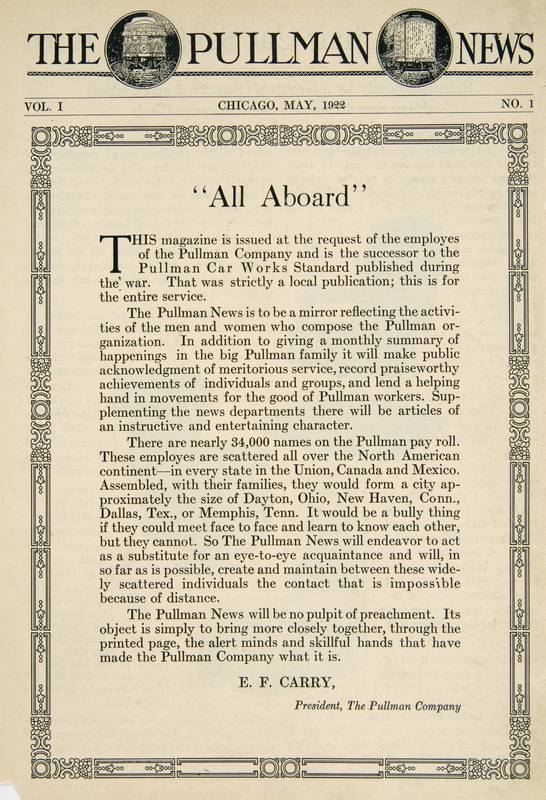

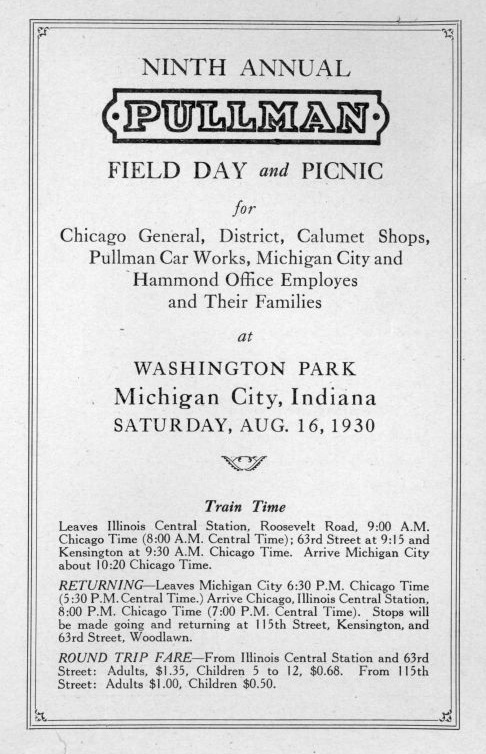

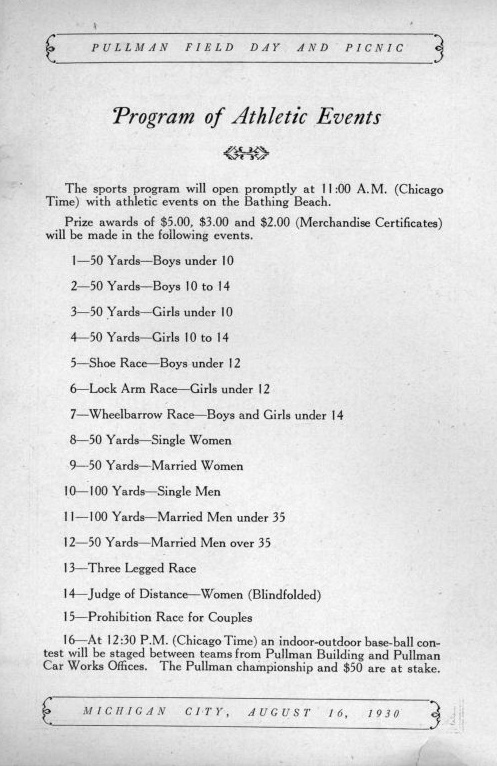

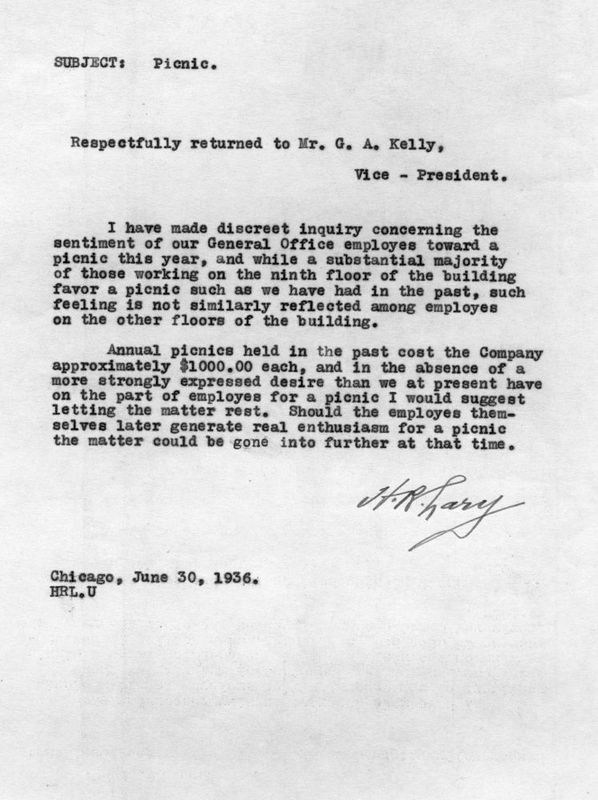

By the dawn of the twentieth century, then, it seemed as if Pullman’s grand experiment had ended. But the death of George Pullman and the end of the Pullman experiment did not stop the Pullman Company from attempting to remain involved in their workers’ social lives. Instead, the Pullman Company became an innovator of what historians call “welfare capitalism,” where the company continued to supplement the wages it paid with non-wage benefits or amenities. The documents collected here convey these new efforts. The company continued to offer workers a myriad of social programs and activities to dissuade them from joining or organizing unions. Picnics, company papers, and even savings banks all became a way for the Pullman Company to recreate the sense of community or family it once hoped the model town would foster.

Employee Representation

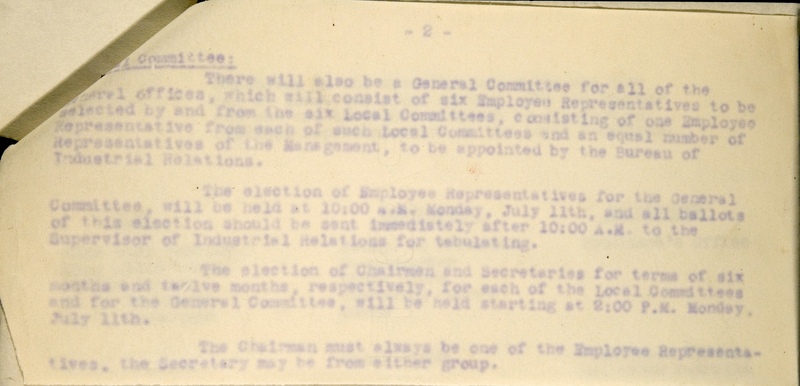

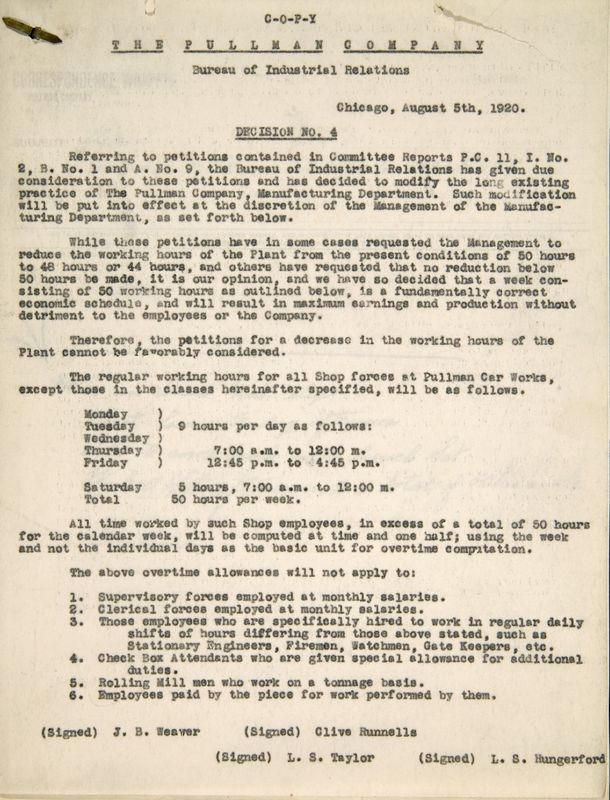

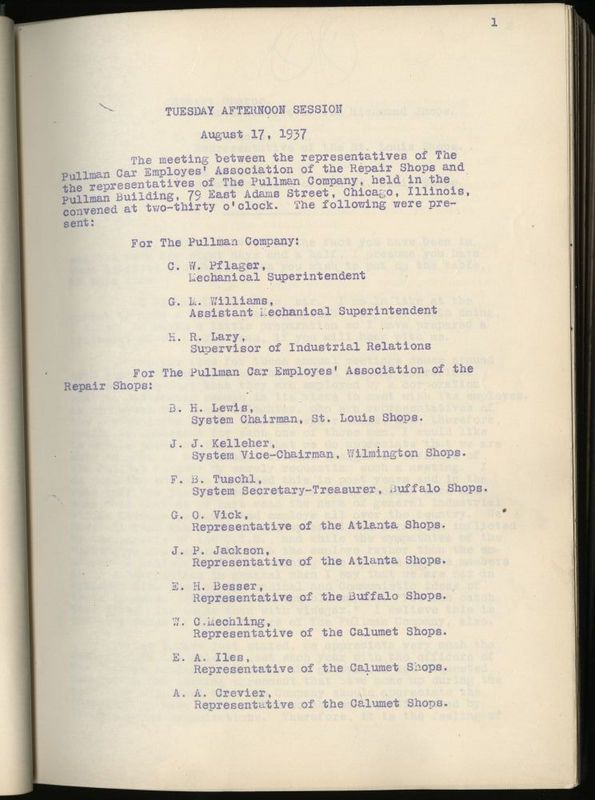

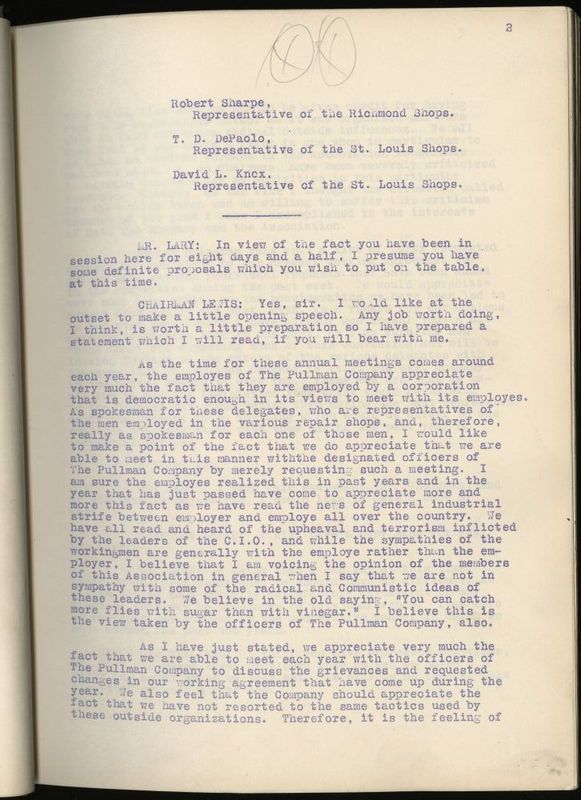

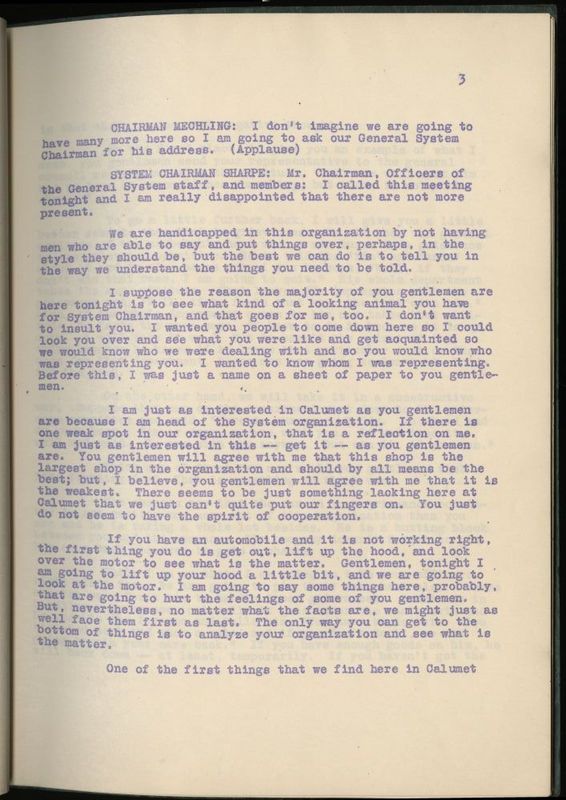

With the Pullman Company no longer able to influence their workers’ social lives by owning their community, the workplace itself became an increasing site of struggle between the company and its employees. Workers continued to attempt organizing new labor unions to negotiate their wages and working conditions. The company, meanwhile, continued to refuse to recognize these unions as their workers’ representatives. In the summer of 1920, however, the Pullman Company proposed a radical new structure for governing workplace relations. Through a newly formed Bureau of Industrial Relations, the company hoped to undercut the need for worker-led unions by creating committees where employees could formally resolve their grievances. Called the Plan of Employee Representation, or the Employee Representation Plan, the Plan organized the company’s workers into a number of Local Committees based on the kinds of jobs they did. Each Local Committee then elected officers who would arbitrate workplace issues alongside representatives from the company. Workers then presented their grievances or wage demands to these committees of workers and managers and hopefully negotiate a resolution. Much like the model town, Pullman executives, especially Bureau of Industrial Relations head F. L. Simmons, saw the Plan as a way to create workplace harmony. But in practice, the Plan would continue to frustrate workers in their efforts to negotiate their working conditions.

Denied Grievances

Pullman workers initially rushed to take advantage of the new Employee Representation Plan. As the oil stained petition above suggests, Pullman workers attempted to work within the new Plan in an attempt to negotiate their wages, hours, and other working conditions. As workers soon discovered, however, the Employee Representation Plan’s structure was titled decidedly in the favor of the company. The company retained the right to deny all grievances, and the company could use the Plan to stall in handingly specific cases. As the minutes of various Local Committee meetings collected here suggest, Pullman workers soon became disillusioned with the Employee Representation Plan and returned to organizing worker-led unions. The most successful campaign against the Plan, however, would come not from within Pullman’s factories, but on its trains.

This page has paths:

This page references:

- Kensington Strike Headquarters

- General Nelson A. Miles

- Tin Shops, c. 1910s

- Many Suffer Want

- Trouble Breaks Out in Pullman

- Burning of Six Hundred Freight-Cars on the Panhandle Railroad, South of Fiftieth Street, on the Evening of July 6th

- Workers at Main Gate

- F. L. Simmons creates the Bureau of Industrial Relations

- Petition of Workers from the Pullman Works

- Illinois Central is Now Tied Up

- King Debs