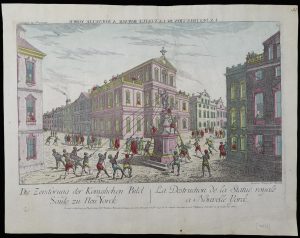

Inaugurated by the revolutionary struggles of North American colonists against Great Britain’s imperial might starting in 1775, the next five decades saw waves of uprisings throughout the Americas against other European colonial powers, notably Spain and Portugal. We often neglect: the status of the American Revolution as just one of many conflicts between European empires; the borderlands of the Revolutions where British territories were contested by Indigenous nations or by the French and Spanish empires; and the conflicted reactions by the new US government and citizens to the other American revolutions of the 1810s through 1830s. As Wim Klooster emphasizes in his book, Revolutions in the Atlantic World: A Comparative History, all of these colonial insurrections can “be understood only in an international context.”

The economic burdens imposed by colonial powers on their colonies converged with Enlightenment thinkers’ ideas about freedom, progress, and representative government to foment protest against the demands of imperial states. These ideas also resonated with many members of oppressed and marginalized populations, including enslaved people, people of color, the Indigenous, the poor, and almost all women. On the other hand, once it had achieved independence, in the nineteenth century the United States responded with deep ambivalence to the cries for equality coming from Latin America. As Caitlin Fitz points out in Our Sister Republics: The United States in an Age of American Revolutions, “For all their universalist rhetoric, white people in the United States had always wanted land, and they had usually been willing to fight for it. . . . That they did so even as they imagined themselves at the forefront of an international movement for freedom was not lost on Spanish-American onlookers.”

Meanwhile, the impact of the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) on its mainland neighbors, both northern and southern, can hardly be overestimated. “As a unique example of a successful black revolution, it became a crucial part of the political, philosophical, and cultural currents” in the Age of Revolutions and beyond, Laurent Dubois argues in Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution, “It became a central cause of the destruction of slavery in the Americas, and therefore a crucial moment in the history of democracy.”

In the United States, news reports and the accounts of exiles from the former colony of Saint-Domingue provoked discussion of abolition and Black capability, stoked fears of violent insurrection, and caused a reexamination of the country’s own revolution and founding documents. Early South American revolutionaries of African descent visited Haiti or were inspired by its example, including José Chirino (Venezuela, 1795), instigators of the “Revolt of the Tailors” (Brazil, 1798), and Francisco Xavier Pirela (Venezuela, 1799). The specter of “another Haiti” also was raised as the justification for merciless suppression of conflicts such as Hidalgo’s revolt in Mexico. And, of course, Haitian president Alexandre Pétion provided material support to Simón Bolívar, “the Liberator” of Venezuela, in exchange for the promise of emancipation.

Constitutions are also at the center of revolutions in the Americas. In The State as a Work of Art: The Cultural Origins of the Constitution, Eric Slauter explores the importance of what we now call the humanities to the framers of the American Constitution, and to the framers of new governments in the Americas more broadly. “Politicians and ordinary people in the early United States considered the state as a work of art. . . . They also believed that successful political constitutions should emerge from the manners, customs, tastes, and genius of the people being constituted . . . the task as many saw it was for humans to organize politics in such a way that the state would both reflect the population and reform it.”

Bolívar and other framers of foundational documents in this period were profoundly influenced by these and similar ideas, drawn from Montesquieu’s writings. Rather than imitating the US Constitution as the guiding light for the Congress of Angostura in 1819, Bolívar proposed his understanding of the French philosopher’s guidance “that laws should be suited to the people for whom they are made; that it would be a major coincidence if those of one nation could be adapted to another; that laws must . . . be in keeping with . . . the religion of the inhabitants, their inclinations, resources, number, commerce, habits, and customs. . . . This is the code we must consult, not the code of Washington!” In other words, better understanding of cultures, histories, religions, and arts should lead to better laws, better government, and better politics—the key being how “the people” being constituted and represented would be imagined, defined, and redefined.

By 1836, the former Latin American colonies of Colombia, Mexico, Chile, Paraguay, Venezuela, Argentina, Peru, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Ecuador, and Bolivia had gained independence from Spain; Brazil from Portugal; and Uruguay from Brazil. That year, Spain formally renounced all claims in the Americas.

En español

Inauguradas por las luchas revolucionarias de los colonos norteamericanos contra el poderío imperial de Gran Bretaña a partir de 1775, las cinco décadas siguientes fueron testigo de oleadas de levantamientos en toda América contra otras potencias coloniales europeas, especialmente España y Portugal. A menudo hacemos caso omiso de: el estatus de la Revolución Americana como sólo uno de muchos conflictos entre imperios europeos; las zonas fronterizas de las revoluciones en las que los territorios británicos fueron disputados por las naciones indígenas o por los imperios francés y español; y las reacciones conflictivas del nuevo gobierno y de los ciudadanos estadounidenses a las otras revoluciones americanas de las décadas de 1810 a 1830. Como subraya Wim Klooster en su libro Revolutions in the Atlantic World: A Comparative History, todas estas insurrecciones coloniales «sólo pueden entenderse dentro de un contexto internacional».

Las cargas económicas impuestas por las potencias coloniales a sus colonias convergieron con las ideas de los pensadores de la Ilustración sobre la libertad, el progreso y el gobierno representativo para fomentar la protesta contra las exigencias de los estados imperiales. Estas ideas también resonaron con muchos integrantes de grupos oprimidos y marginados, como los esclavizados, la gente de color, los indígenas, los pobres y casi todas las mujeres. Por otro lado, una vez alcanzada la independencia, en el siglo XIX Estados Unidos respondió con una profunda ambivalencia a los gritos de igualdad procedentes de América Latina. Como señala Caitlin Fitz en Our Sister Republics: The United States in an Age of American Revolutions: «A pesar de toda su retórica universalista, los blancos de Estados Unidos siempre habían querido tierras, y normalmente habían estado dispuestos a luchar por ellas […] Que lo hicieran incluso cuando se imaginaban a sí mismos a la cabeza de un movimiento internacional por la libertad no pasó desapercibido para los espectadores hispanoamericanos».

Mientras tanto, el impacto de la Revolución Haitiana (1791-1804) en sus vecinos del continente, tanto del norte como del sur, difícilmente puede ser sobrestimado. «Como ejemplo único de una revolución negra exitosa, se convirtió en una parte crucial de las corrientes políticas, filosóficas y culturales» en la Era de las Revoluciones y más allá —sostiene Laurent Dubois en Vengadores del Nuevo Mundo: la historia de la revolución haitiana—. «Se convirtió en una causa central de la destrucción de la esclavitud en las Américas y, por tanto, en un momento crucial de la historia de la democracia».

En Estados Unidos, las noticias y los relatos de los exiliados de la antigua colonia de Saint-Domingue provocaron debates sobre la abolición y la capacidad de los negros, avivaron el temor a una insurrección violenta y provocaron un replanteamiento de la propia revolución y los documentos fundacionales del país. Los primeros revolucionarios sudamericanos de ascendencia africana visitaron Haití o se inspiraron en su ejemplo, como José Chirino (Venezuela, 1795), los instigadores de la Conjura dos Alfaiates o Revuelta de los Sastres (Brasil, 1798), y Francisco Xavier Pirela (Venezuela, 1799). El fantasma de «otro Haití» también se planteó como justificación para la supresión implacable de conflictos como sucedió con la revuelta de Hidalgo en México.

Naturalmente, el presidente haitiano Alexandre Pétion proporcionó apoyo material a Simón Bolívar, «el Libertador« de Venezuela», a cambio de la promesa de emancipación.

En The State as a Work of Art: The Cultural Origins of the Constitution, Eric Slauter examina la importancia que tuvieron lo que ahora designamos como humanidades para los artífices de la Constitución estadounidense, y para los artífices de los nuevos gobiernos en las Américas en general. «Al inicio del país, los políticos y la gente común de los Estados Unidos consideraban el Estado como una obra de arte […]. También pensaban que las constituciones políticas exitosas debían nacer a partir de los modales, costumbres, gustos y genio del pueblo que se constituía […]. La tarea, tal y como la veían muchos, era que los seres humanos organizaran la política de tal manera que el Estado reflejara a la población y la reformara».

Bolívar y otros redactores de documentos fundacionales en este periodo estuvieron profundamente influenciados por estas y otras ideas similares, extraídas de los escritos de Montesquieu. En lugar de imitar la Constitución de los Estados Unidos como guía para el Congreso de Angostura en 1819, Bolívar propuso su entendimiento del consejo del filósofo francés «de que las leyes deben ser adecuadas al pueblo para el cual se hacen; que sería una gran coincidencia que las de una nación pudieran ser adaptadas a otra; que las leyes deben […] estar de acuerdo con la religión de los habitantes, sus inclinaciones, recursos, número, comercio, hábitos y costumbres […]. ¡Este es el código que debemos consultar, no el código de Washington!». En otras palabras, una mejor comprensión de las culturas, las historias, las religiones y las artes debería conducir a mejores leyes, a un mejor gobierno y a una mejor política, siendo la clave la forma de imaginar, definir y redefinir al «pueblo» que se constituye y representa.

Para 1836, las antiguas colonias latinoamericanas de Colombia, México, Chile, Paraguay, Venezuela, Argentina, Perú, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Ecuador y Bolivia se habían independizado de España, Brasil de Portugal y Uruguay de Brasil. Ese año, España renunció formalmente a todas sus posesiones en América.