Plan of Employe Representation

1 2021-04-19T17:35:55+00:00 Newberry DIS 09980eb76a145ec4f3814f3b9fb45f381b3d1f02 16 1 Pullman Car & Manufacturing Corporation, Plan of Employee Representation, 1924. 2021-04-19T17:35:55+00:00 Newberry DIS 09980eb76a145ec4f3814f3b9fb45f381b3d1f02This page has paths:

- 1 2021-04-19T17:35:56+00:00 Newberry DIS 09980eb76a145ec4f3814f3b9fb45f381b3d1f02 On the Trains Collection Newberry DIS 1 structured_gallery 2021-04-19T17:35:56+00:00 Newberry DIS 09980eb76a145ec4f3814f3b9fb45f381b3d1f02

This page is referenced by:

-

1

2021-04-19T17:35:54+00:00

On the Trains

1

image_header

2021-04-19T17:35:54+00:00

Symbols of Service

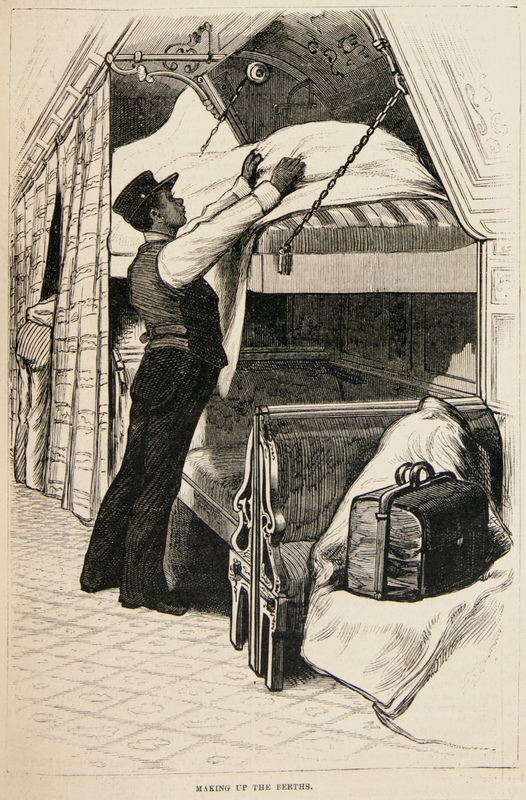

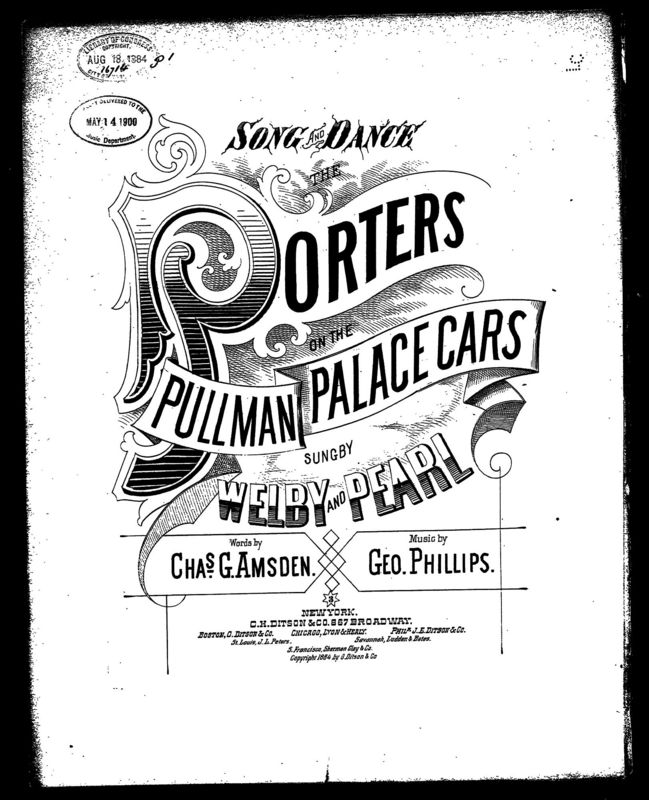

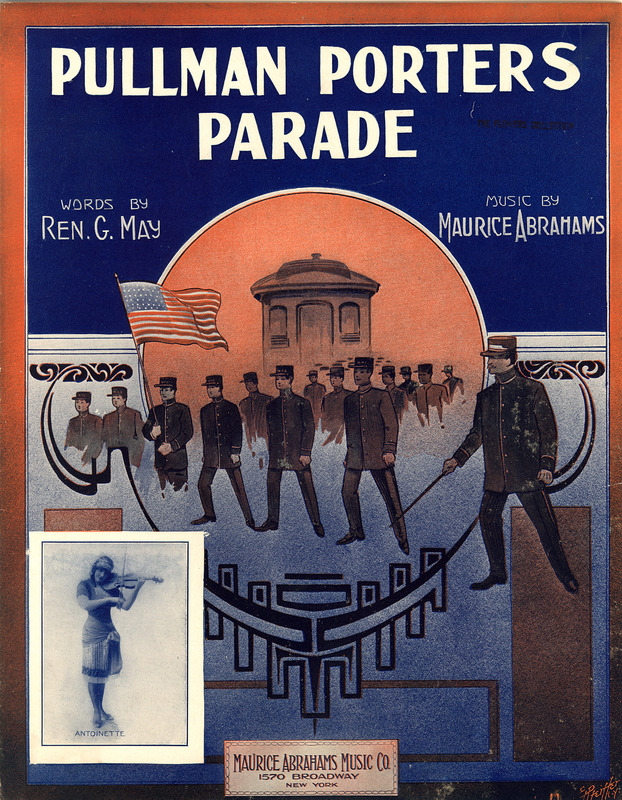

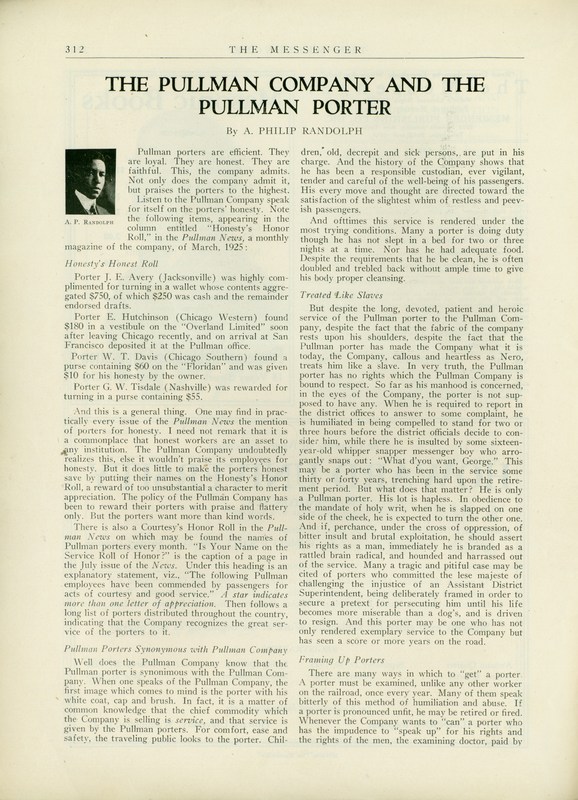

While the Pullman strike thrust the company and its model town into the national spotlight, the planned community was actually only a small portion of the company’s broader public image. Most of the traveling public first encountered Pullman’s vision not in his town but on his trains. And no other feature of Pullman’s palace cars more embodied his desire for social order and high-class service than the porters who cared for passengers while they traveled. Ever present, impeccably dressed, and always ready to assist passengers, Pullman Porters literally became the face of the Pullman Company.

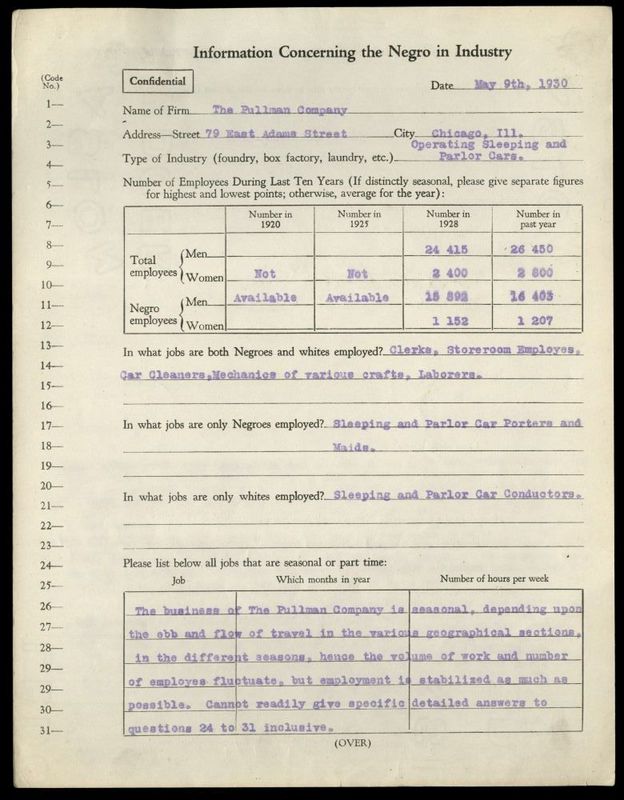

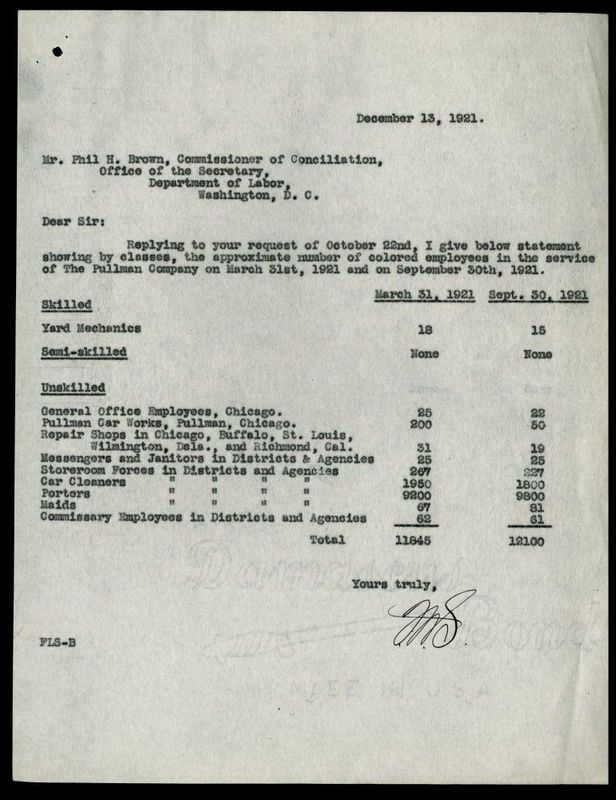

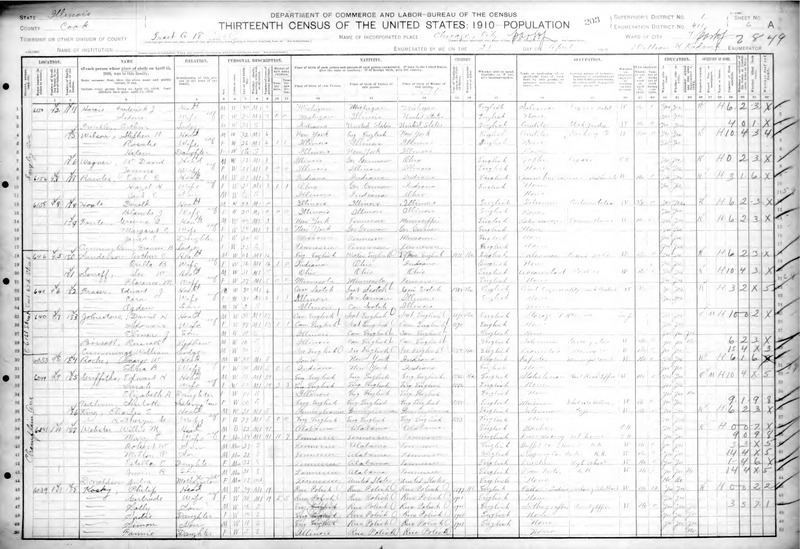

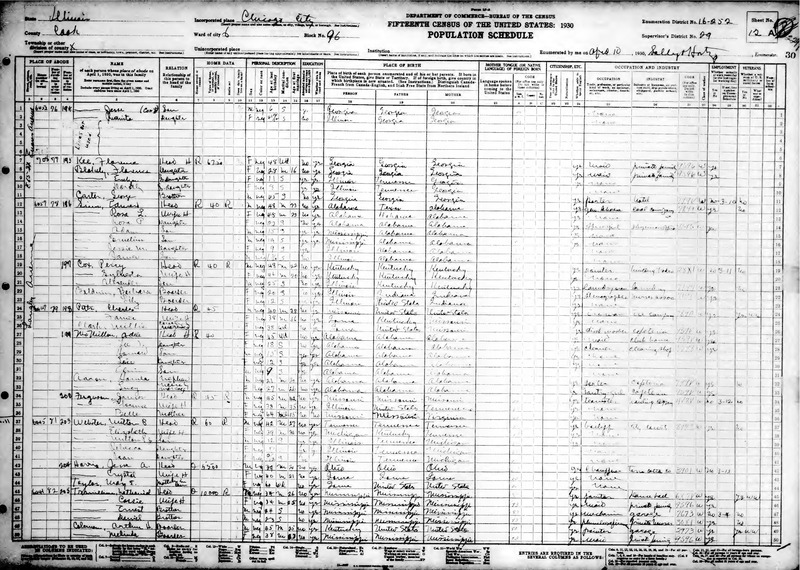

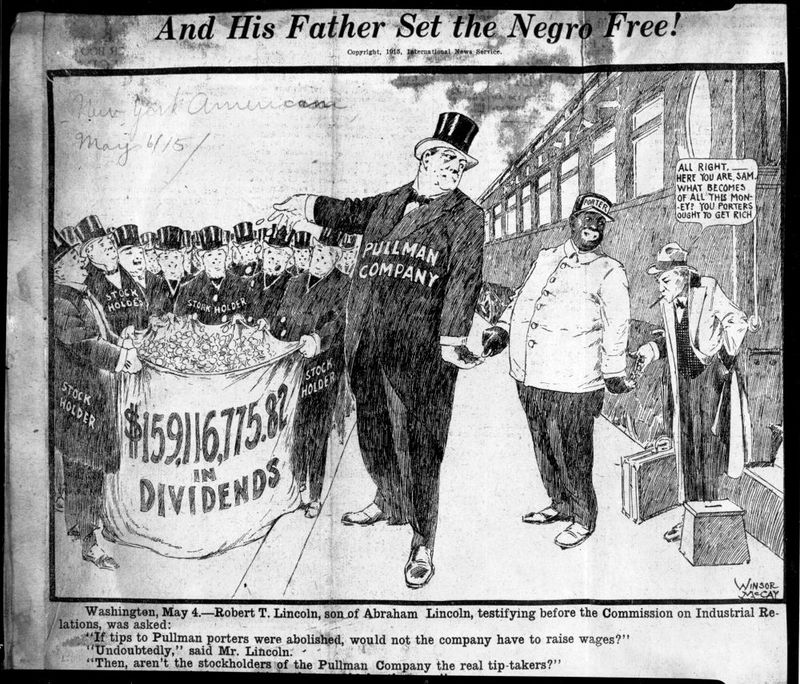

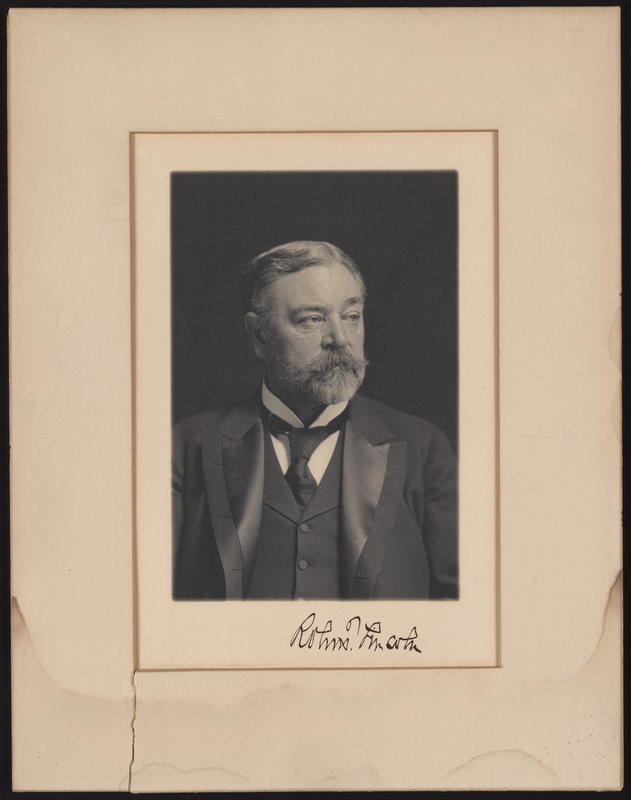

From the company’s earliest days, Pullman solely hired black workers to serve as porters. Pullman’s recruitment was in part altruistic, but also deeply paternalistic and informed by racial pressuppositions. A longtime Republican and supporter of Abraham Lincoln, Pullman saw the position as an opportunity for the millions of former slaves recently freed by the Civil War. Yet Pullman’s choice to hire only black men and women to serve as porters and maids reflected his belief that the only position suitable black workers was to serve white people. The only positions open to black workers in the model town of Pullman, for example, was the Hotel Florence’s service staff such as waiters, cooks, and maids. The documents collected here reflect the centrality of the porter to the Pullman experience, while also conveying the segregated nature of their work.

The Chrysalis

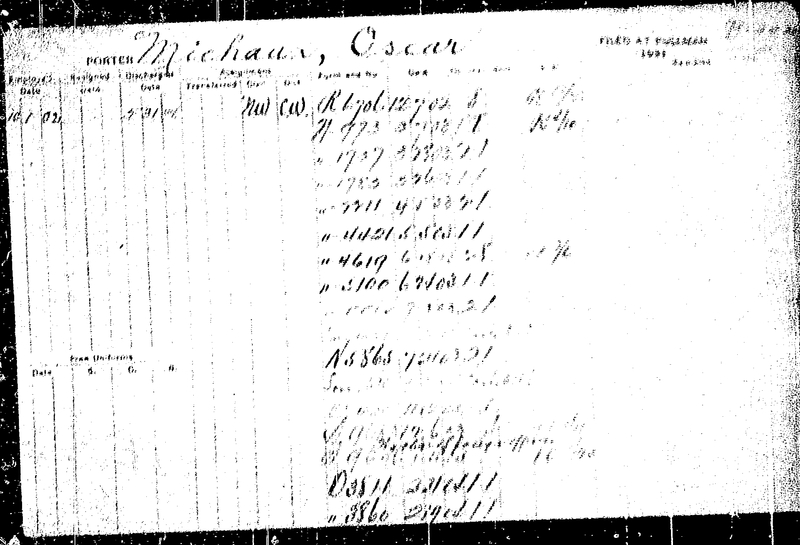

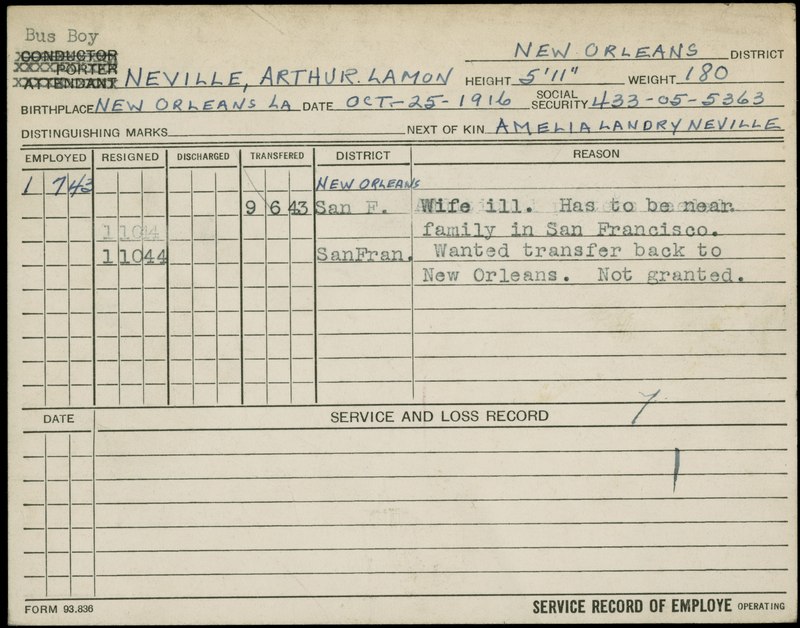

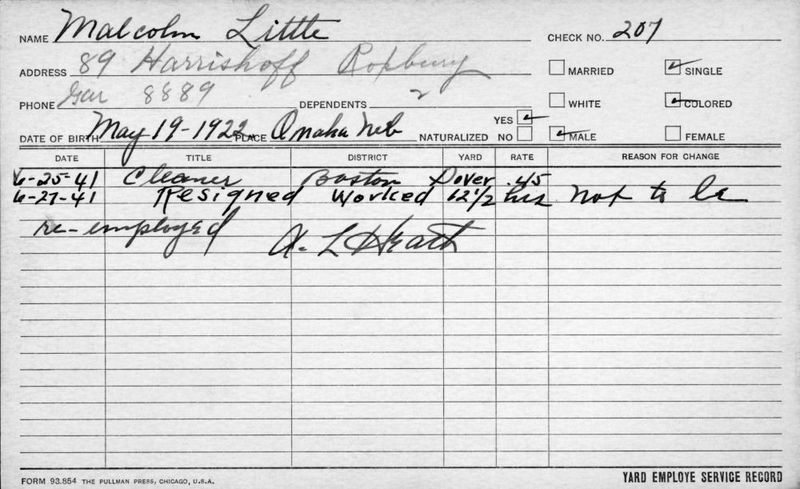

Though the Pullman Company only employed African Americans in segregated positions, these jobs remained important opportunities for many black workers. The wages porters received were some of the highest available to black workers anywhere, and the distinction that came with working in a uniformed service industry provided an important alternative to the agriculture work African Americans had long been subject to. To work as a Pullman Porter, then, became one of the most prized jobs within the African American community. The Pullman Company intentionally cultivated a positive image through benevolent donations to black churches and universities, thereby both directly and indirectly contributing to the development of the country’s free black community in the half century after the Civil War. Later black leaders, artists, and innovators such as Oscar Peterson, Thurgood Marshall, and E. D. Nixon were either porters or the children of porters. On display here are the service records for former porters Oscar Micheaux, the first African-American to produce a feature film; Arthur Lamon Neville, Sr., whose sons would go on to form the Neville Brothers; and Malcom Little, who would later adopt the name Malcom X through his involvement with the Nation of Islam. The documents here suggest some of the ways in which the Pullman Porter became both a contemporary cultural icon as well as an important social network within the African American community.

Always on His Feet

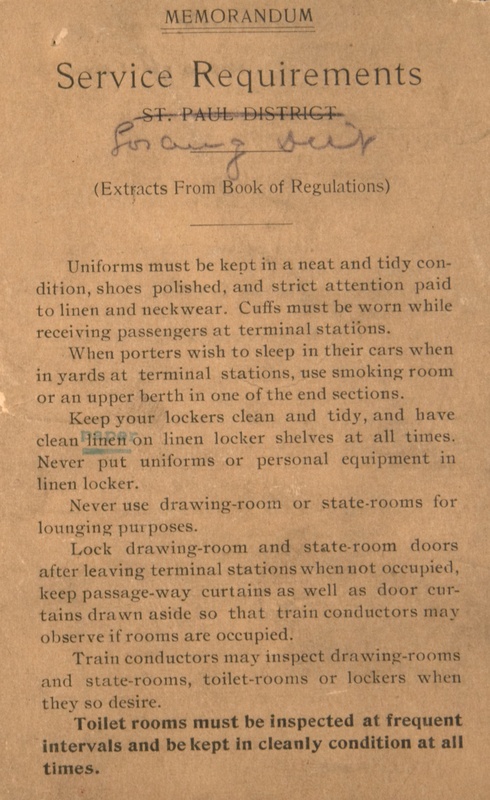

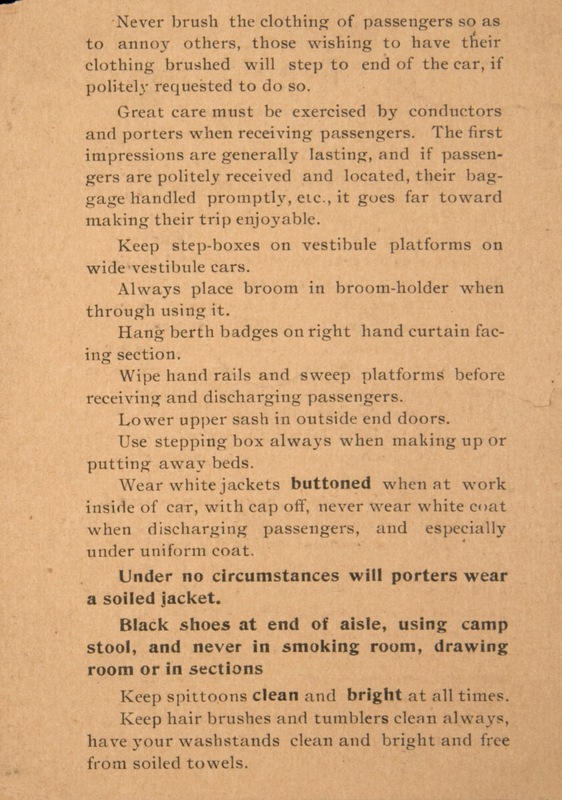

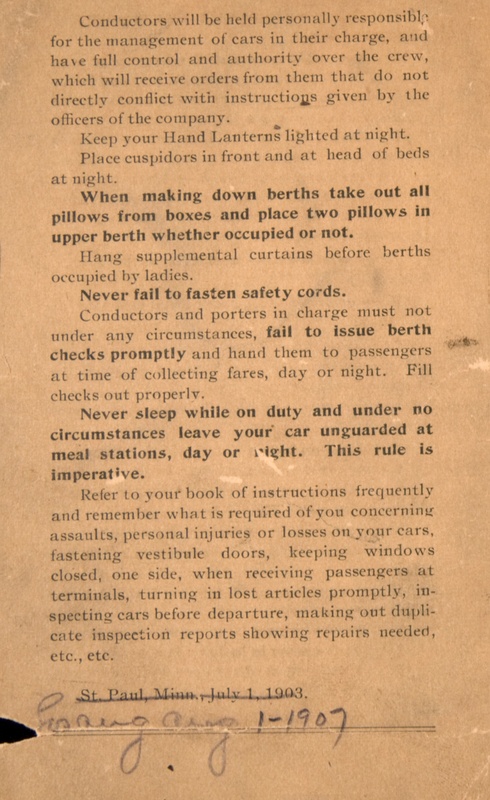

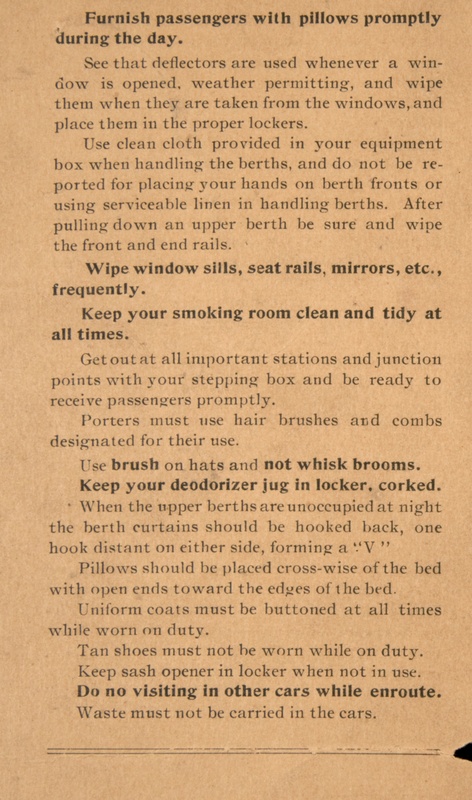

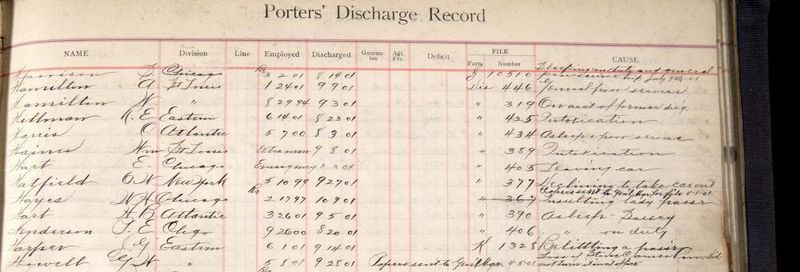

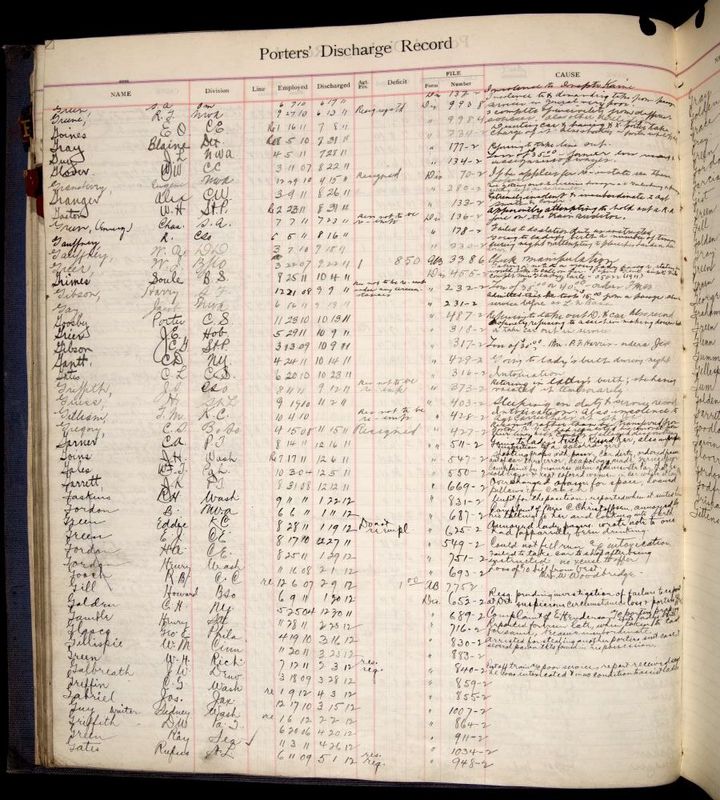

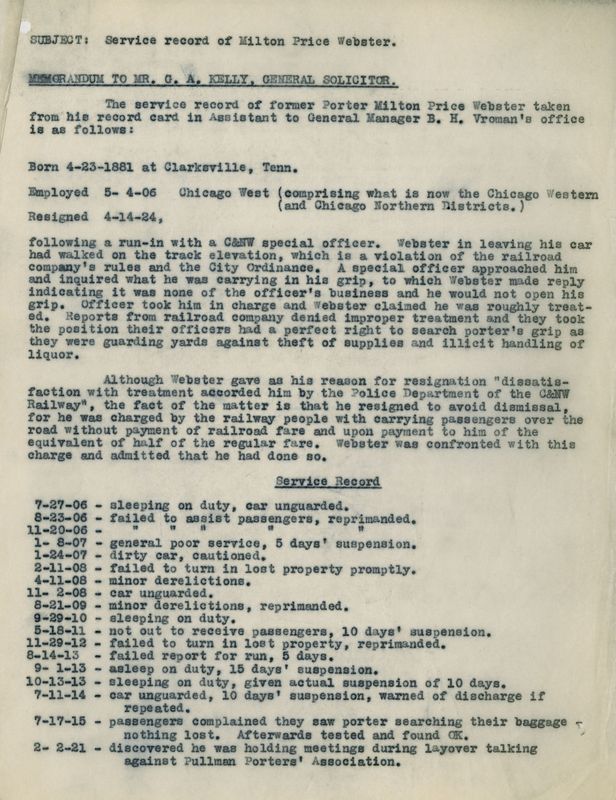

Regardless of how prized being a Pullman Porter was, working as a porter remained difficult, onerous work. In addition to the long hours that could come with working overnight trains, porters were also held to exacting standards of dress, conduct, and comportment. In a reflection of the company’s paternalistic and prejudiced hiring practices, they subject porters to a level of oversight and degradation white workers did not face. Porters could be fired without appeal if white travellers, especially white women, complained porters were too informal, or “familiar,” with them. Moreover, every porter, no matter his name, was to go by “George” while working. The requirement was an homage to the company’s founder, but was also intended to relieve the passengers of the trouble of having to learn a black man’s name.

A Real Labor Union

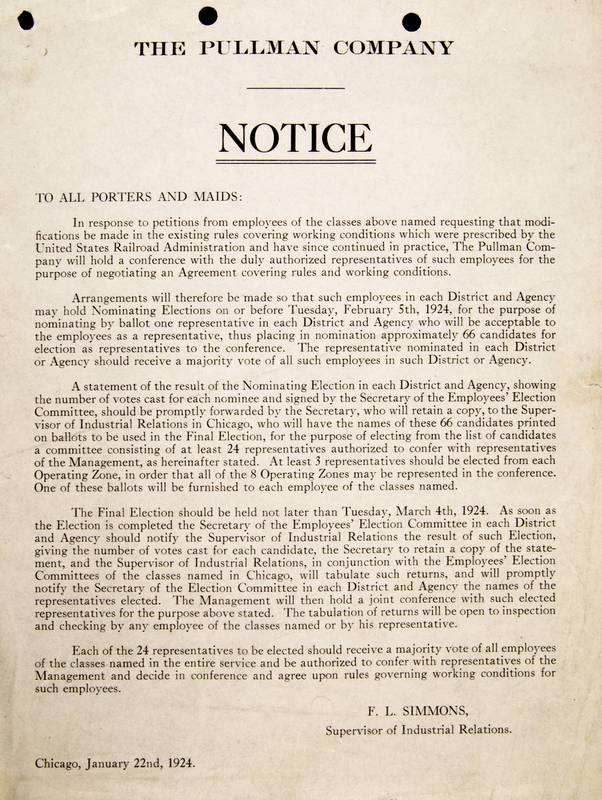

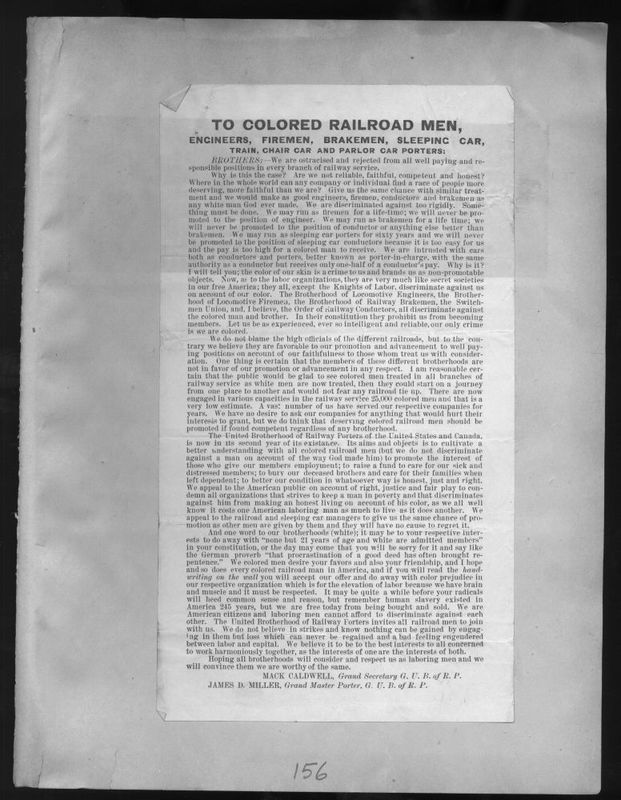

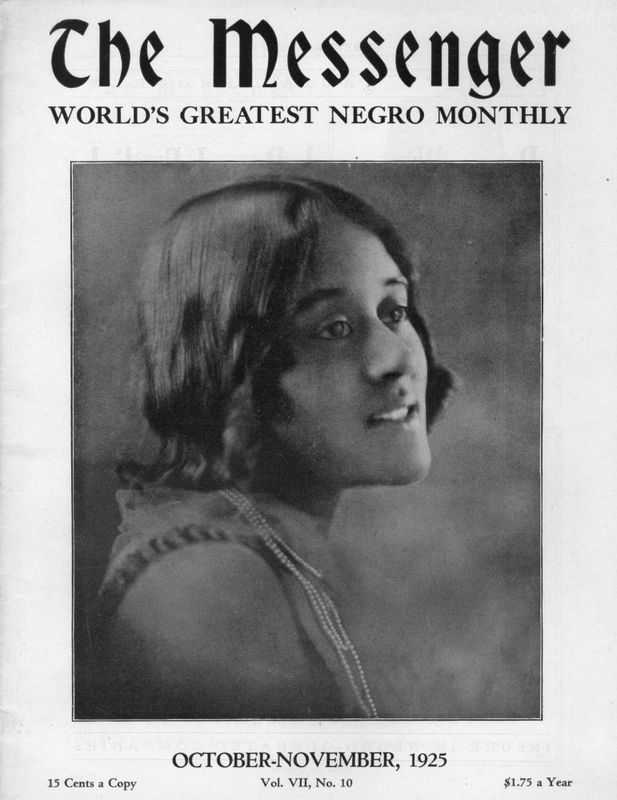

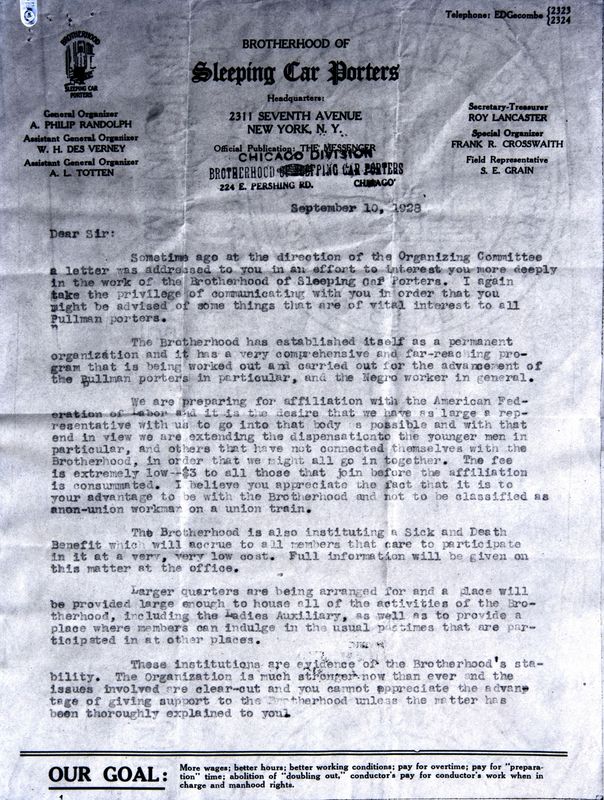

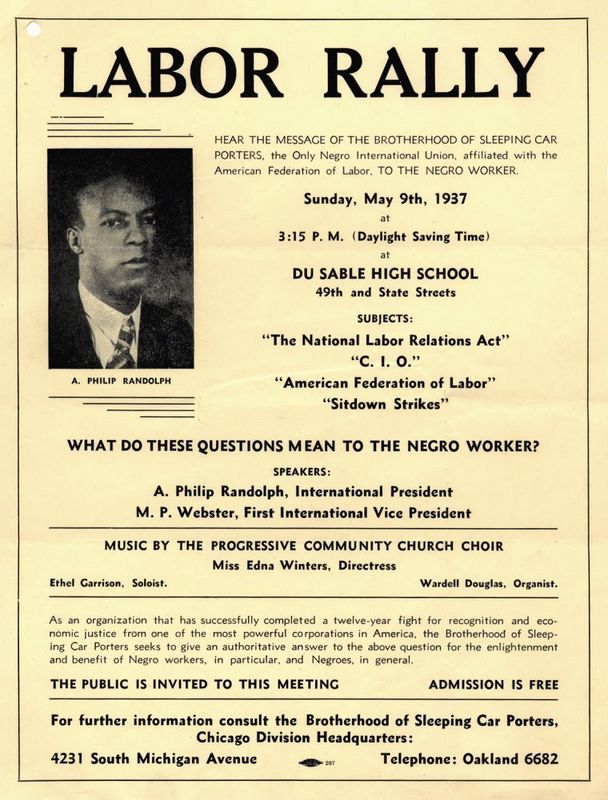

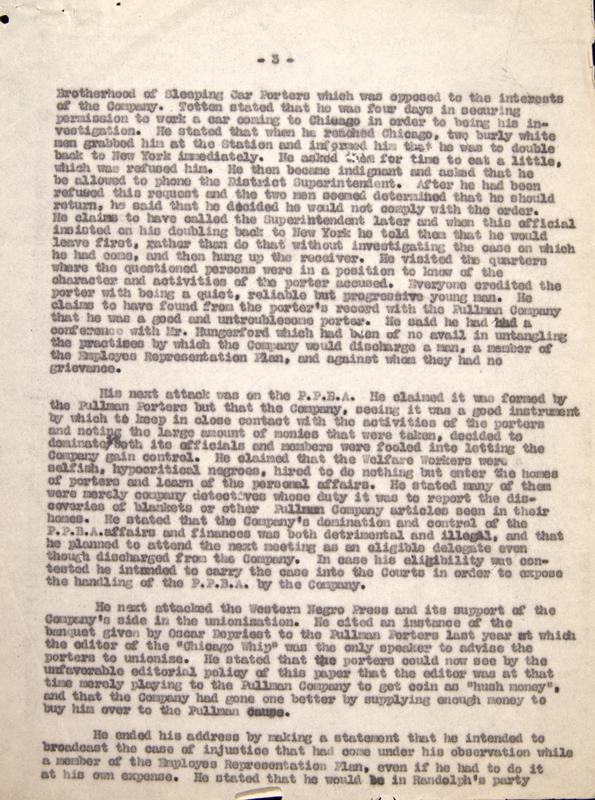

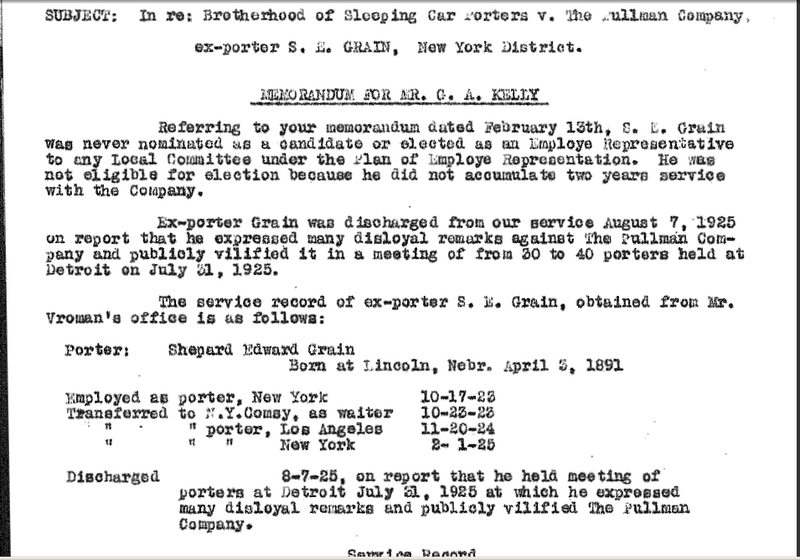

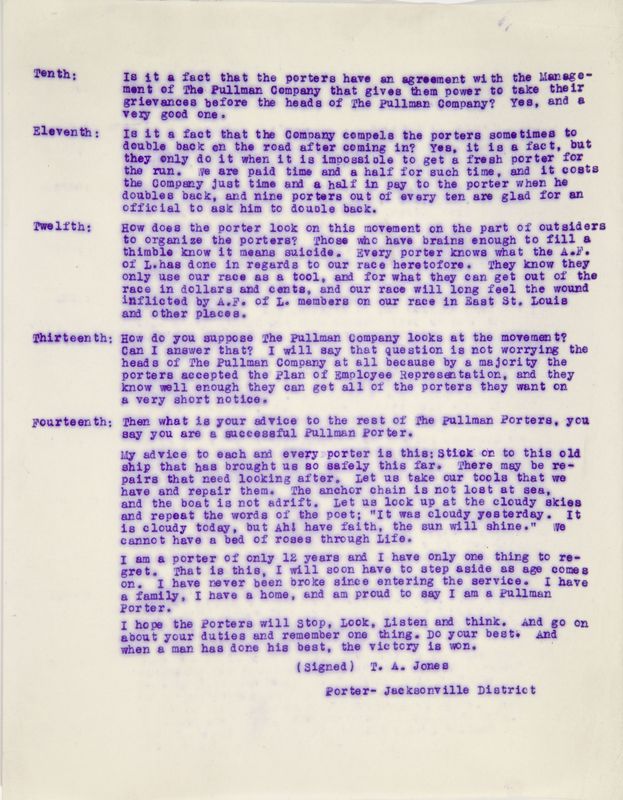

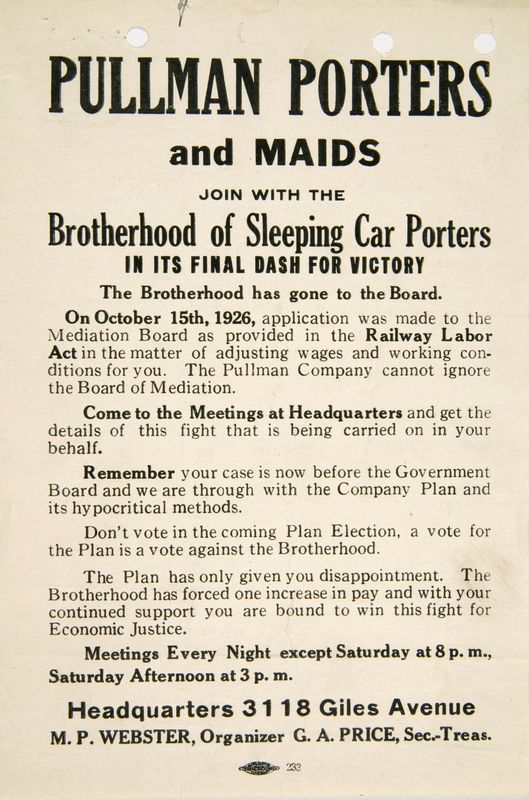

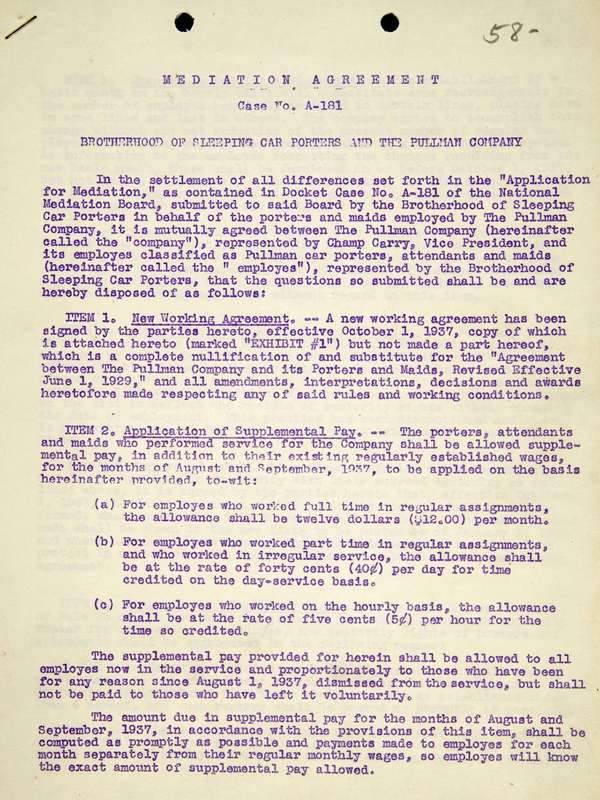

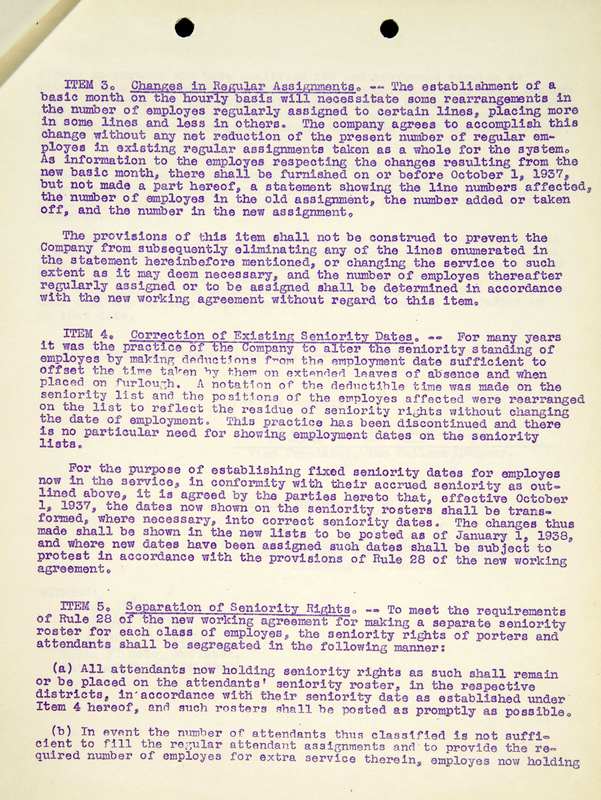

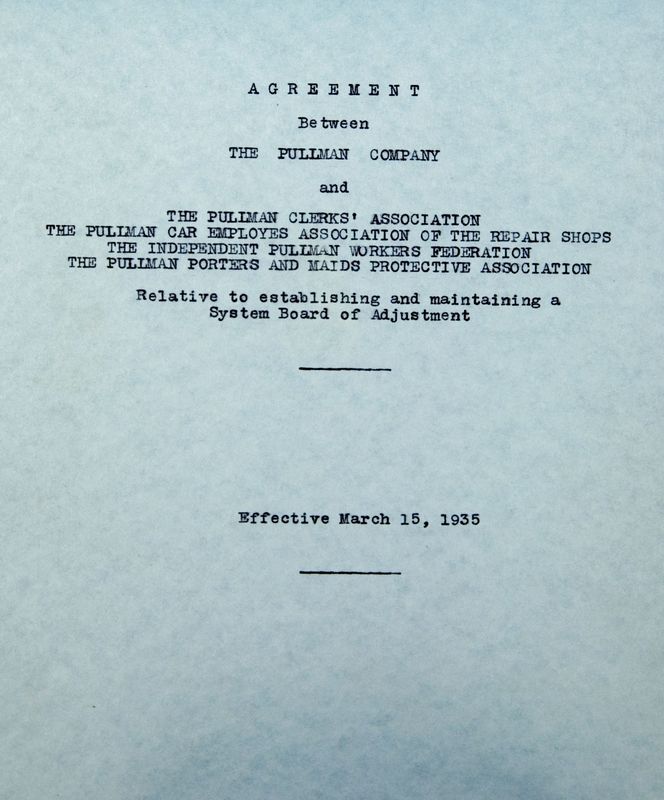

Though Pullman Porters were subjected to a number of racially-based expectations and demeaning working conditions, their outlet for addressing these grievances was exactly the same as every other Pullman employee. Like Pullman’s factory workers, porters had been attempting to organize since the 1880s. In fact, Pullman Porters may have joined with the American Railway Union in their 1894 boycott of Pullman cars, which would have crippled the company during the strike. The ARU, however, refused to admit black workers, undercutting even the possibility of a coalition. With the advent of the Bureau of Industrial Relations, however, porters came under the Employee Representation Plan just like the workers at the Pullman shops. Unlike the company’s industrial workers, however, porters immediately protested the new Plan as part of a much larger campaign against their working conditions. Beginning in the 1920s, a number of porters reached out to activist A. Philip Randolph to head up a new organizing effort. Randolph was renowned in labor and early Civil Rights circles as publisher of a popular Civil Rights magazine titled The Messenger and as an organizer that helped unionize a number of black workers in New York’s hotels. By 1925 Randolph and a number of porters had organized the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first African-American led union to be recognized by the American Federation of Labor. Under Randolph’s leadership, the Brotherhood appealed to porters both as workers as well as black men. As the documents here convey, a victory for the Brotherhood would mean a victory not only for porters but also for the black community by challenging the company’s discriminatory working conditions.

A Porter's Story

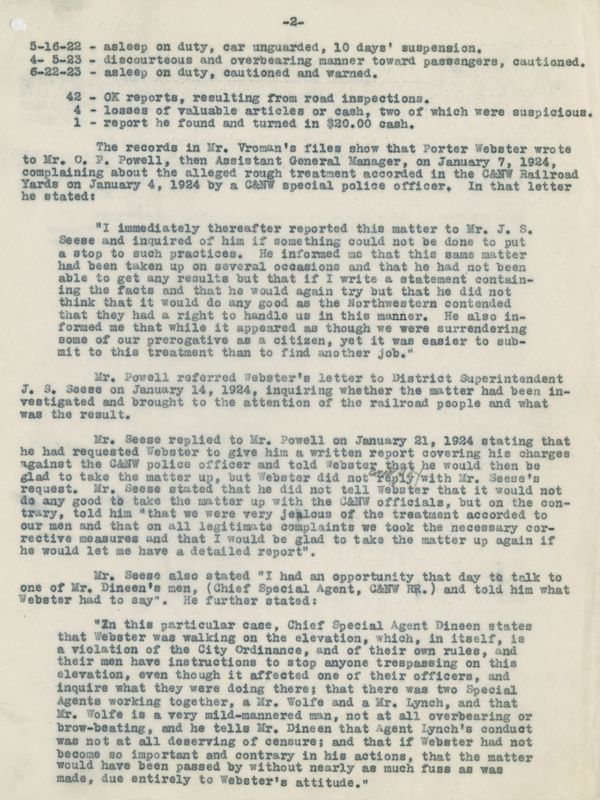

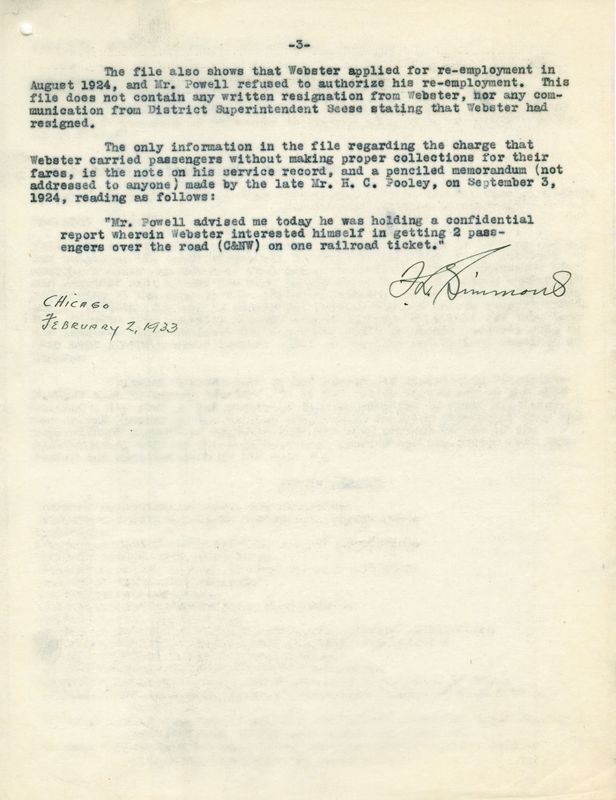

Milton P. Webster would become one of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters most prominent leaders. He was a part of the earliest organizing efforts alongside Randolph, and would hold national positions within the Brotherhood as well as heading up the union’s Chicago Division. Focusing on a single life like Webster provides a unique opportunity to explore an individual’s relation to the Pullman Company. According to these documents, what was Webster’s work experience like? What drew him to the Brotherhood? And as a Chicago resident, what was his relationship to the model town that supposedly stood at the center of Pullman’s public image?

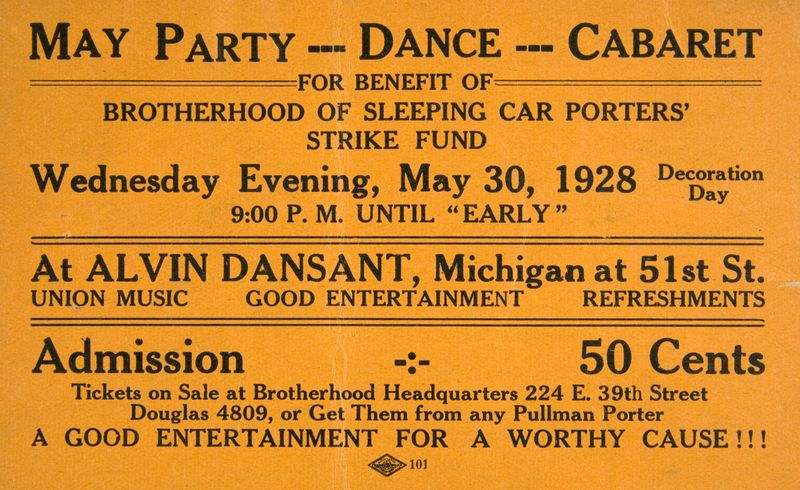

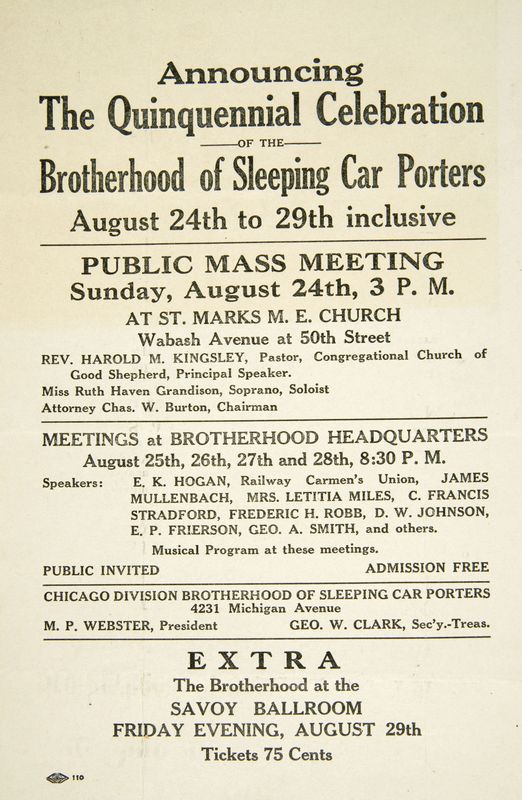

Building the Brotherhood

As Webster’s life suggests, frustrations and grievances growing out of the work experience led many porters to look favorably upon the Brotherhood. But the campaign that led to the Brotherhood’s formation was a long one that involved far more than just porters on their jobs. In the same way that porters were culturally and financially important to the entire African American community, so too was the black community essential in the organization of the Brotherhood. Debate clubs, lecture series, summer socials, and even annual galas, balls, and dances were as important to the Brotherhood as shop floor petitions and strike. Women were essential in these endeavors. They were not only instrumental in the organization of the Brotherhoods social life, but also helped fund the union through these activities.

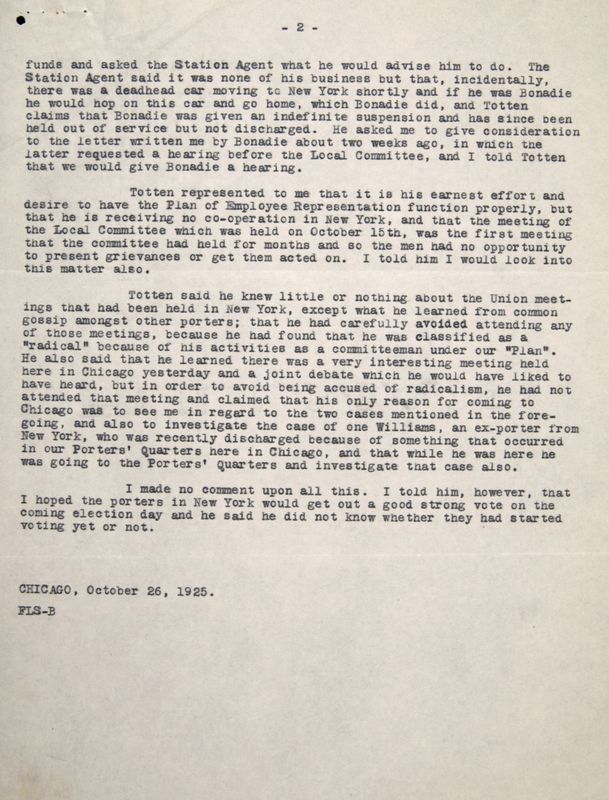

Surveillance

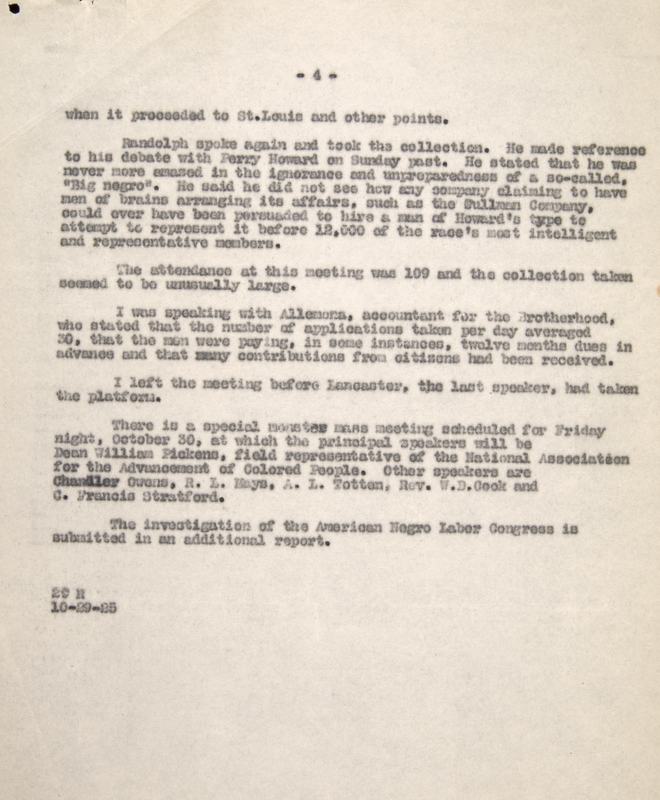

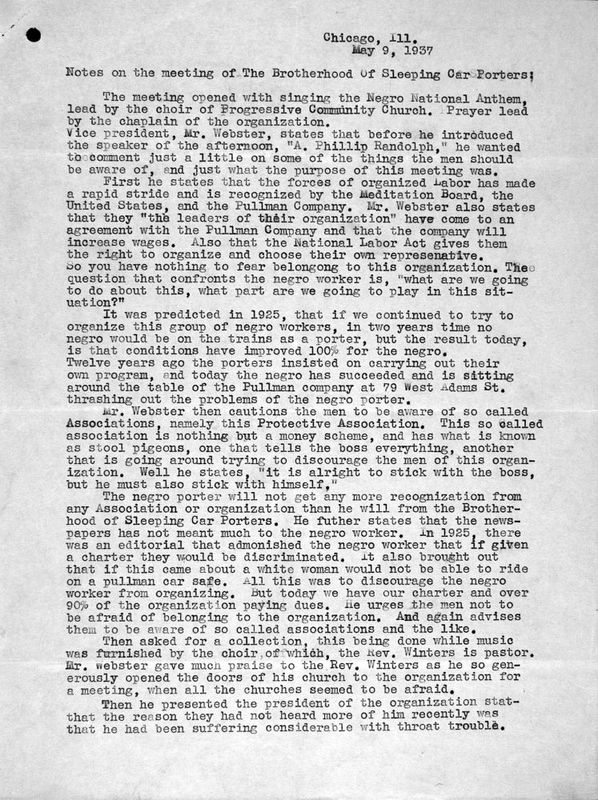

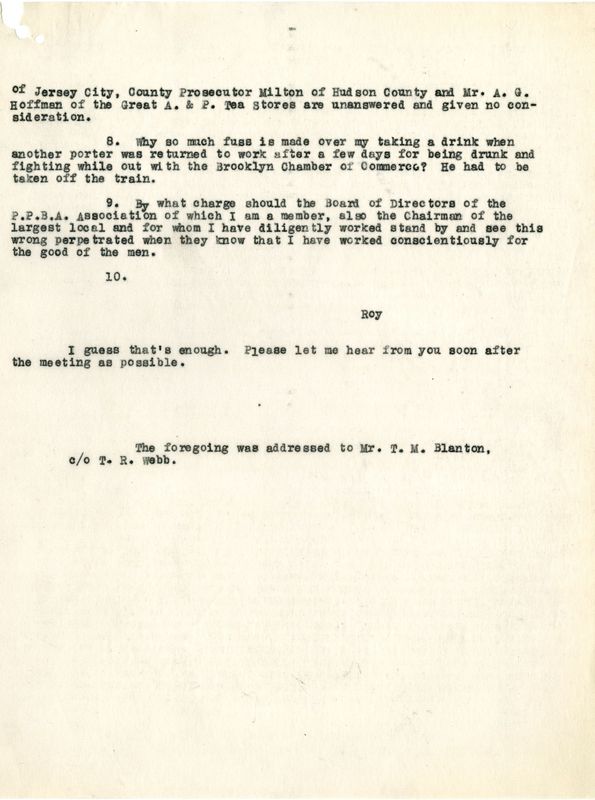

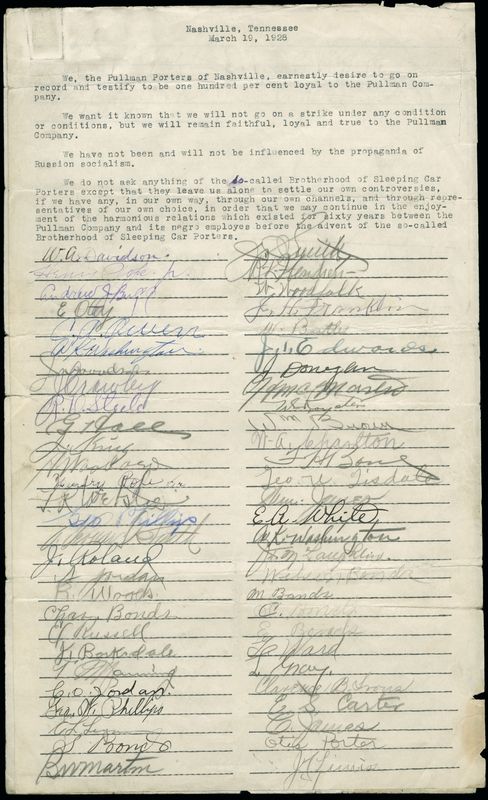

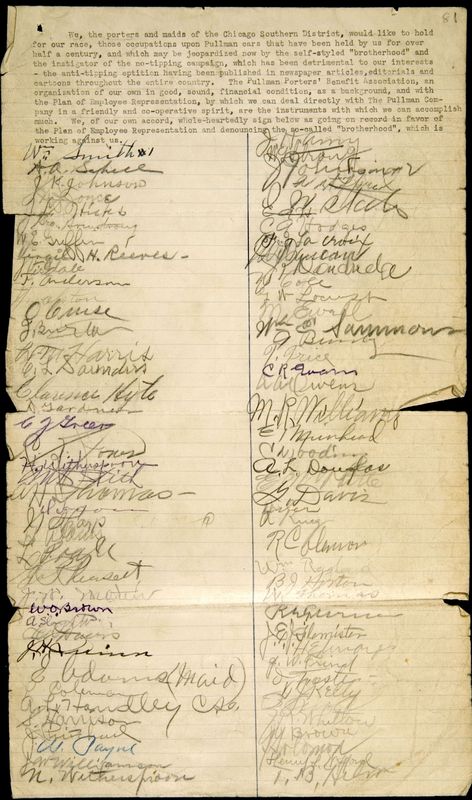

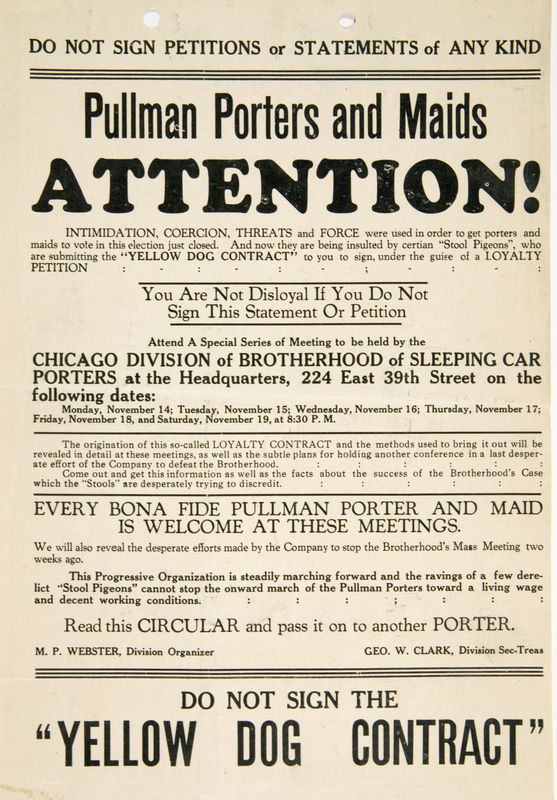

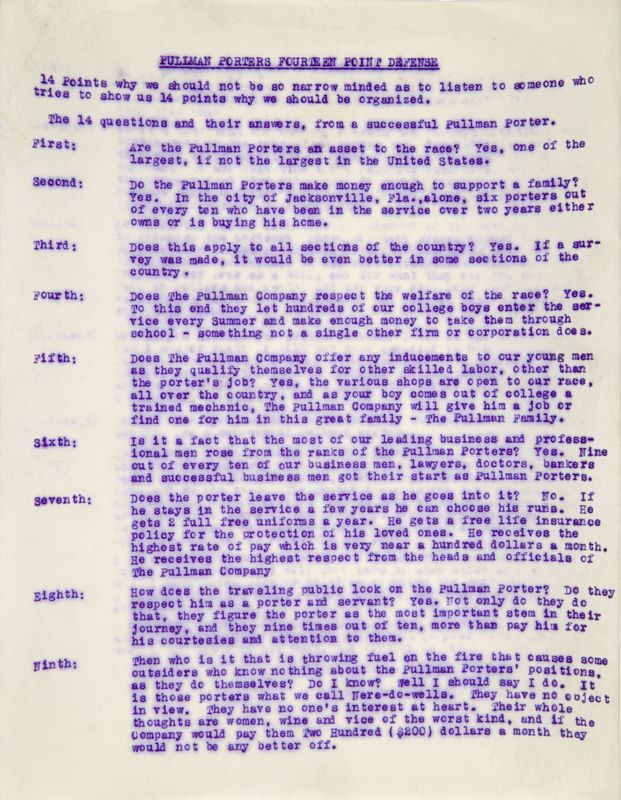

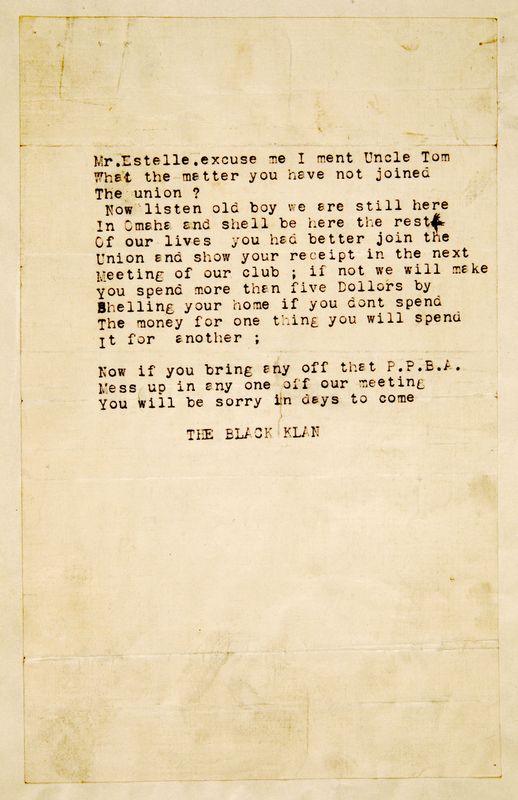

Though the Brotherhood was founded in 1925, porters had been organizing against the Pullman company for decades. The struggle to improve their working conditions would continue long after the Brotherhood’s organization as well. The length of this campaign was in part due to the almost constant efforts by the Pullman Company to thwart the union. The Brotherhood stood as a direct threat to the Employee Representation Plan, and the Pullman Company employed nearly any tactic to stall the union’s growth. The documents collected here provide an unprecedented glimpse into a company’s efforts to prevent a the organization of a union. Preserved because the company was engaged in a lawsuit with the porters at the time the company closed, they illustrate a pervasive anti-union sentiment within the railroad industry. Individual workers involved in the brotherhood were followed, union meetings were infiltrated and spied upon, and workers were required to sign “loyalty oaths” promising to never join or organize a union.

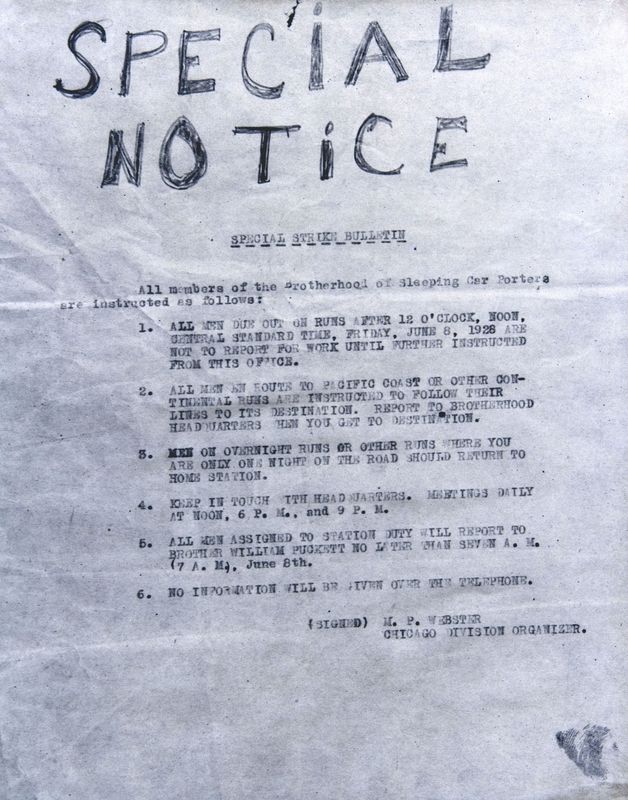

Action Has Started

In the end, the tactics the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters employed proved more powerful than the Pullman Company’s obstructions. By the 1930s, the Brotherhood had won the support of the majority of Pullman Porters, while the passage of pro-labor legislation during the New Deal provided avenues for the Brotherhood to organize officially. The 1934 National Labor Relations Act (also known as the Wagner Act) outlawed the existence of company unions like the Employee Representation Plan, and provided a governing structure by which the Brotherhood could apply to represent the porters. Within a year of the Act’s passage, the porters successfully voted to have the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters serve as their bargaining agent, forcing the Pullman Company to recognize the union. By 1937, the Brotherhood had successfully organized its first contract with the company, paving the way for other Pullman workers, even the workers in the model town, to organize their own unions.

Above: St. Louis Brotherhood Parade, c. 1940. Chicago History Museum, ICHi39911.