Attention Workingmen!

1 2021-04-19T17:35:49+00:00 Newberry DIS 09980eb76a145ec4f3814f3b9fb45f381b3d1f02 16 1 Attention Workingmen! Newberry Library Archives. 2021-04-19T17:35:49+00:00 Newberry DIS 09980eb76a145ec4f3814f3b9fb45f381b3d1f02This page has paths:

- 1 2021-04-19T17:35:49+00:00 Newberry DIS 09980eb76a145ec4f3814f3b9fb45f381b3d1f02 In the City Collection Newberry DIS 1 structured_gallery 2021-04-19T17:35:49+00:00 Newberry DIS 09980eb76a145ec4f3814f3b9fb45f381b3d1f02

This page is referenced by:

-

1

2021-04-19T17:35:49+00:00

In the City

1

image_header

2021-04-19T17:35:49+00:00

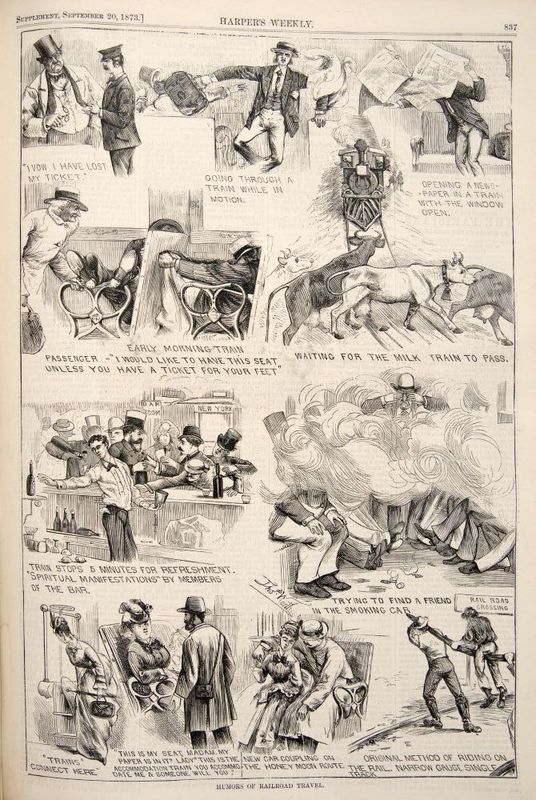

Discomforts of Rail Travel

In 1869, just two years after George Mortimer Pullman had incorporated the Pullman Palace Car Company, the U.S. government completed construction of the nation's first Transcontinental Railroad. In addition to connecting the country’s two coasts, the feat symbolized the growing distances the American public could travel by rail. In the decades that followed, railroad companies laid thousands more miles of track that connected greater distances and even more remote locales, eventually allowing individuals to reach nearly every corner of the nation. But long distance travel was not without its nuisances. The documents here convey some of the sentiments associated with long-distance travel, especially overnight travel. The cramped conditions, lack of amenities, and general bustle of rail traffic all contributed to what one observer called the “discomforts of rail travel.”

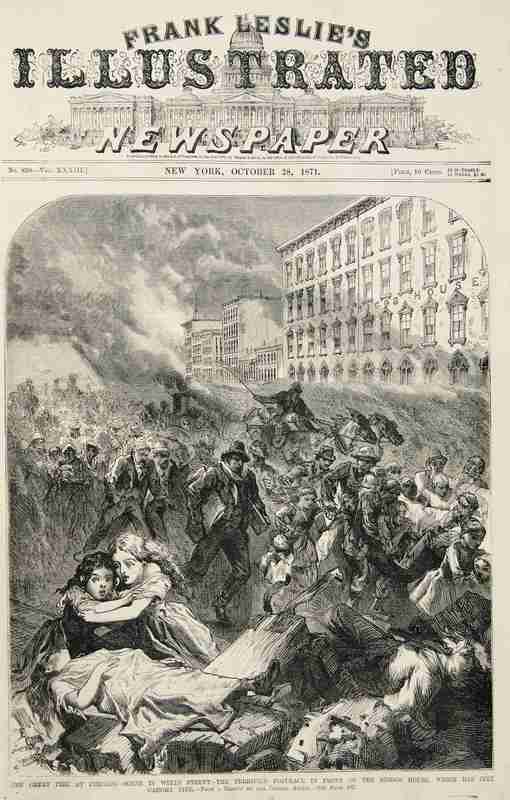

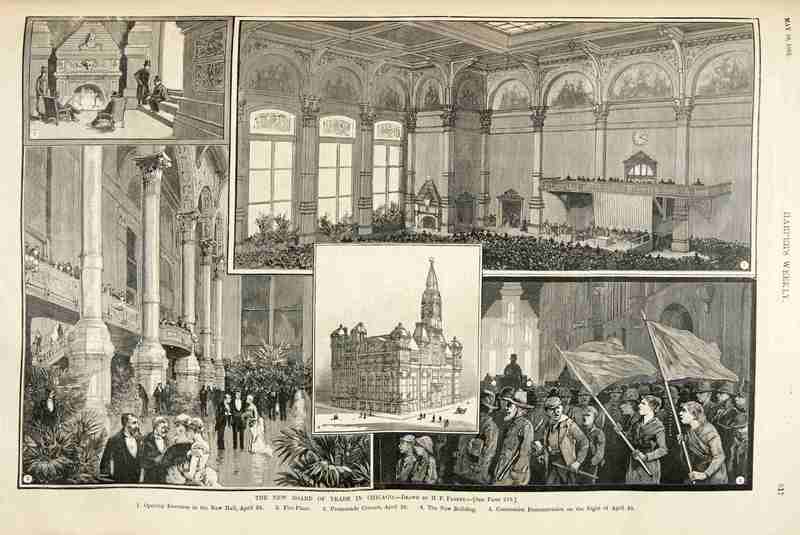

Discomforts of City Life

The growth of America’s railway system was both accompanied and propelled by a corresponding growth in the nation’s cities. Nearly eighty percent of the population lived in rural areas in the 1860s, but by 1900 more than forty percent of the nation lived in an urban setting. Within another twenty years, most of the country would live in communities the U.S. Census defined as urban. European immigrants and native-born rural migrants drove this urban growth. Many arrived to their destination by rail, hoping to find work in factories. Chicago witnessed the most spectacular growth, eclipsing a million residents in 1890 after having only a hundred thousand in 1860. Such rapid expansion, however, bred a host of uniquely urban ailments. The illustrations here are popular representations of urban life in Chicago, including coverage of the 1871 Chicago fire. Much like the complaints surrounding the discomforts of rail travel, they portray urban life as crowded, dirty, unsafe, and bereft of unsanitary, and bereft of modern benefits.

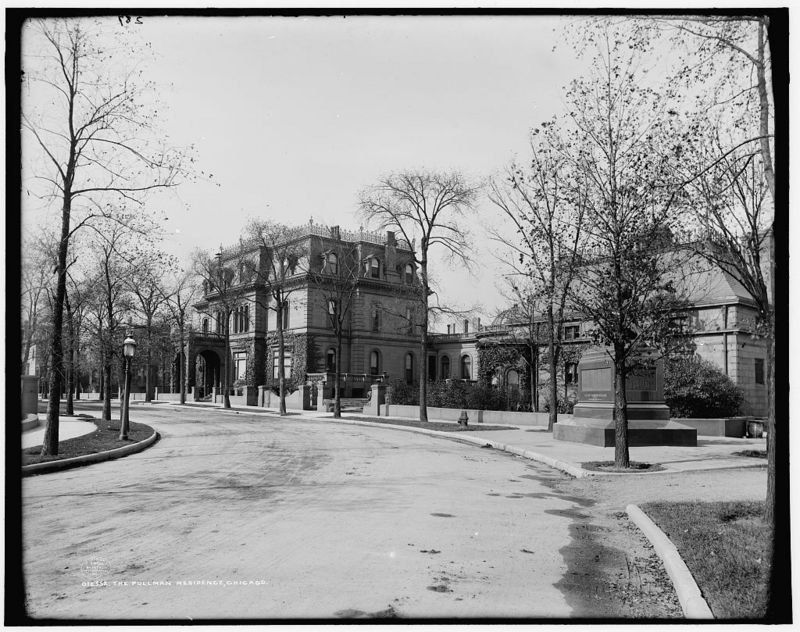

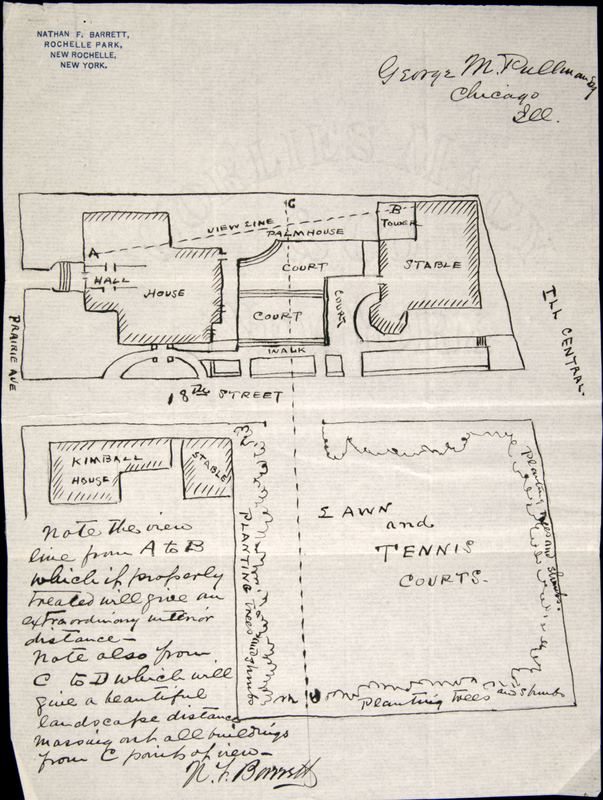

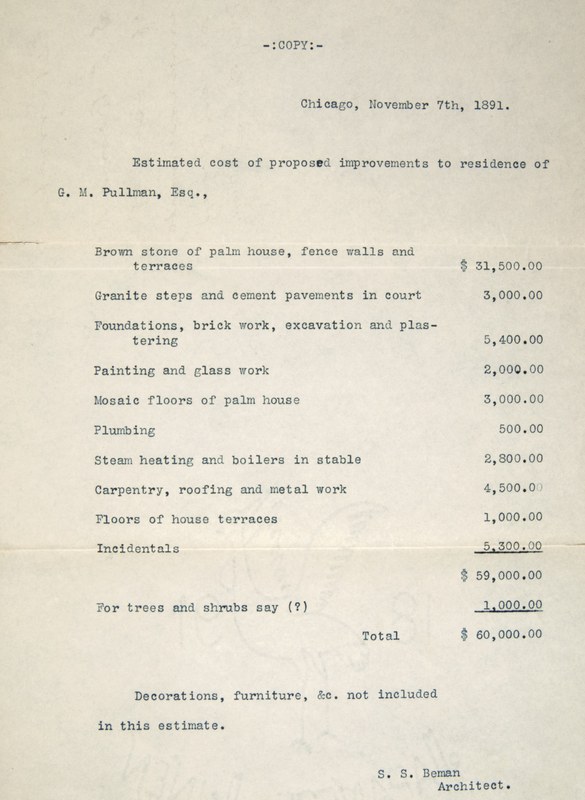

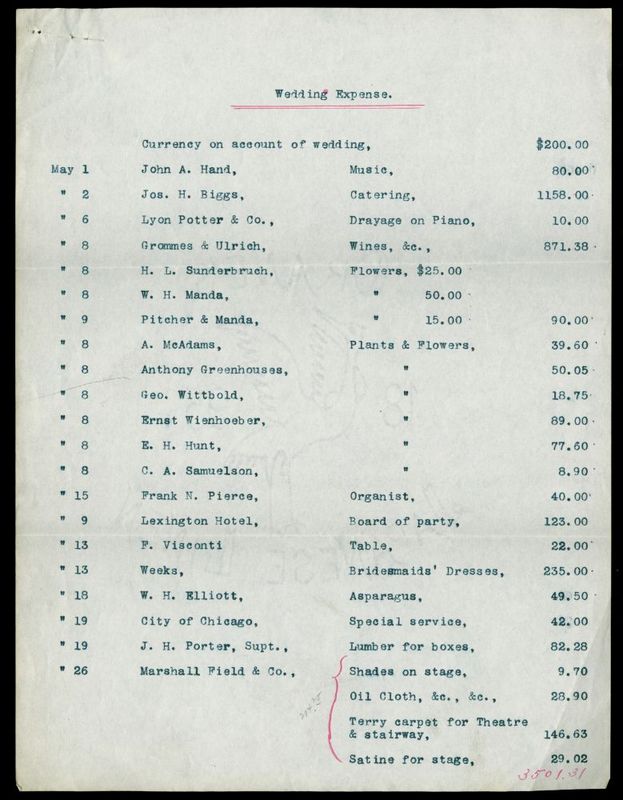

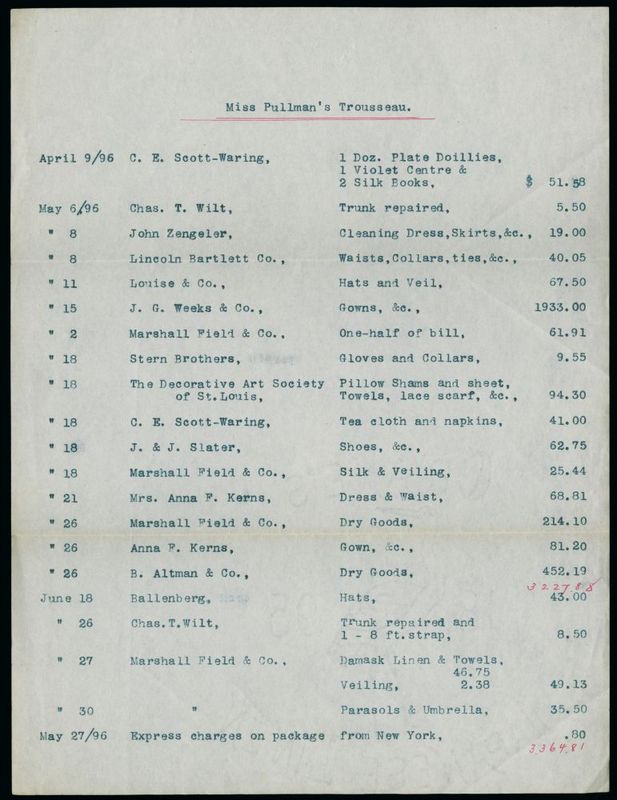

George Pullman's Chicago

Despite popular representations of urban life as crowded and dangerous, conditions in Chicago were by no means uniform. Consider the daily life of Pullman Palace Car Company founder George Mortimer Pullman. Born in upstate New York in 1831, Pullman came to Chicago in the 1850s where he became famous for helping raise several city blocks by six feet to install its new sewer system. After spending several years in Colorado where he became wealthy dealing in the transportation of miners, Pullman returned to Chicago to focus on the construction of sleeping cars. In 1877, Pullman commissioned architects to build a mansion on Prairie Avenue where many of Chicago’s business elite lived such as Marshall Field and Philip Armour. The documents here not only show Pullman’s massive home (torn down in 1922 by Pullman’s wife Harriett), but also provide a glimpse into the contrasts of urban life.

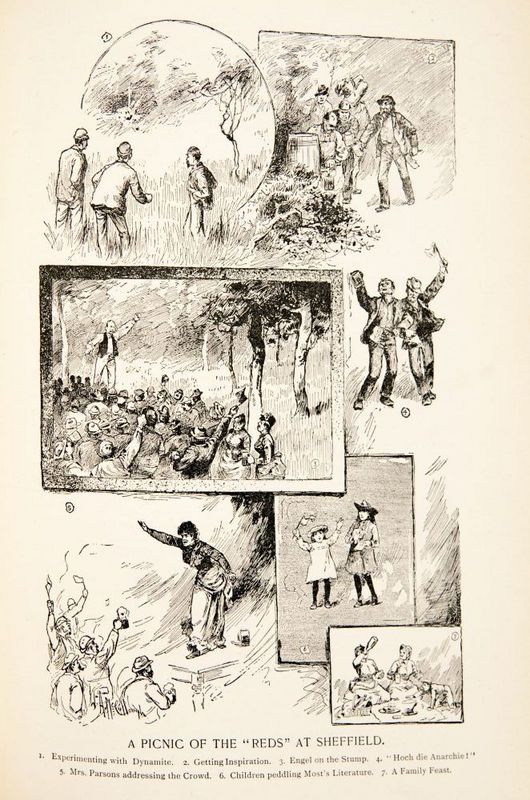

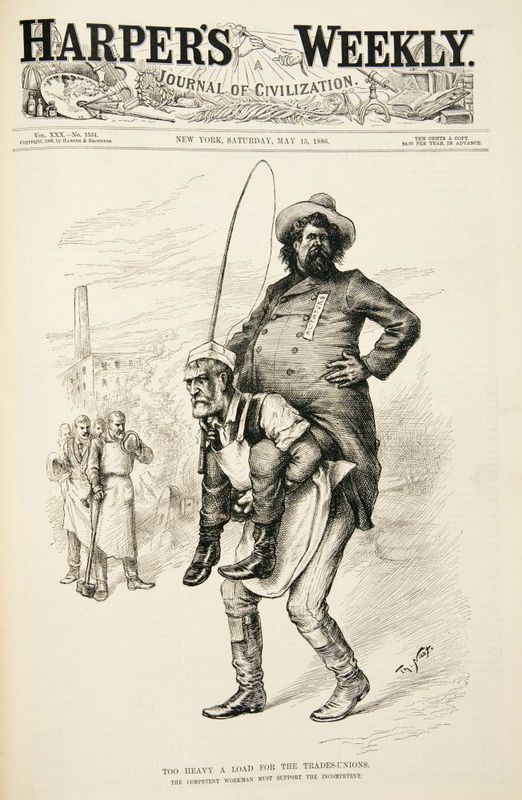

Banners of the Social Revolution

By the 1880s, the dense, unsanitary living conditions of many urban centers prompted city residents across the country to mount significant protests to improve their circumstances. Many working people identified the city’s economic inequality of urban life as the cause. For decades, working people had sought to negotiate a greater share of industrialization’s profits through trade unions and other labor organizations. But beginning in the late 1870s, there was a growing sentiment among some labor activists that capitalism itself was responsible for the workingman’s plight. In cities across the country, anarchist leagues and socialist political parties grew to protest America’s economic disparity. Nowhere was this movement stronger than in Chicago. There workers, many of them German immigrants experienced in labor activism, built a vibrant coalition of Socialist and Anarchist societies. The documents collected here convey some of the demands of these labor activists. Though popular representations that portray radicals as unkempt maniacs, they convey their call for a more equitable distribution of wealth.

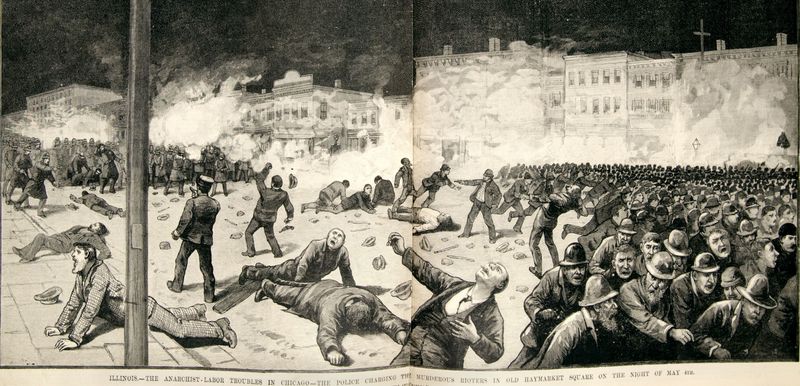

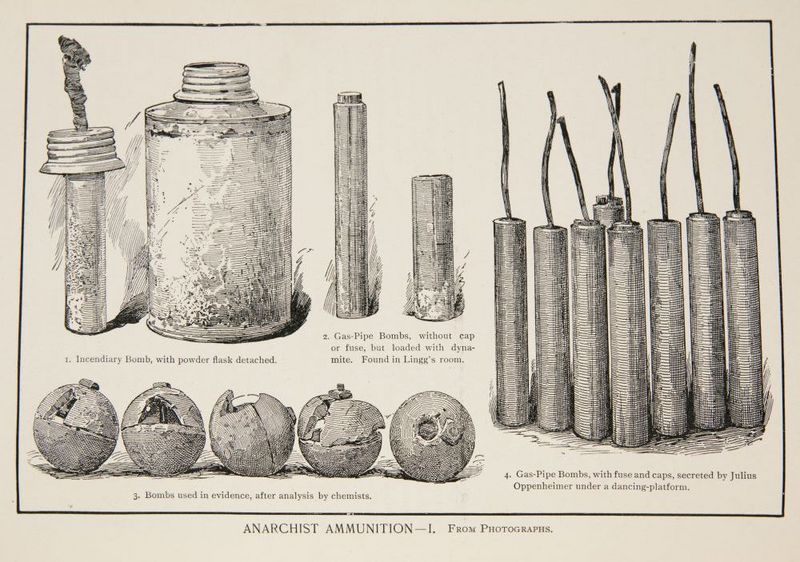

Labor Troubles

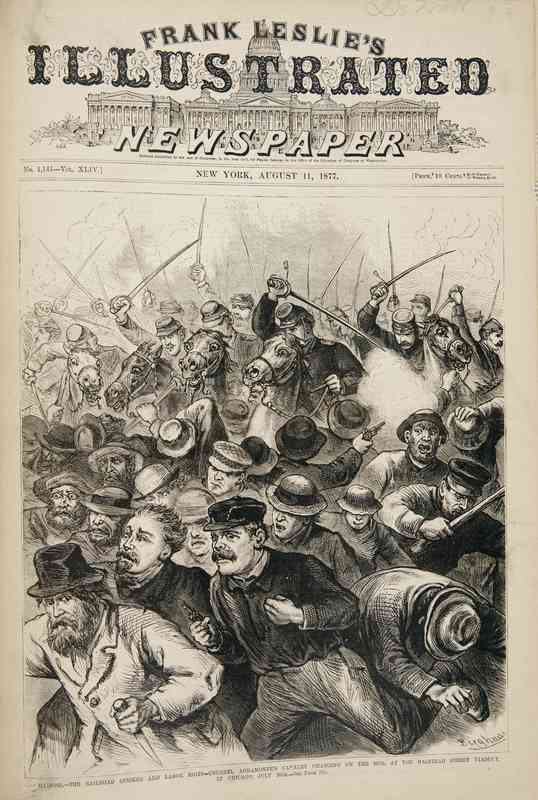

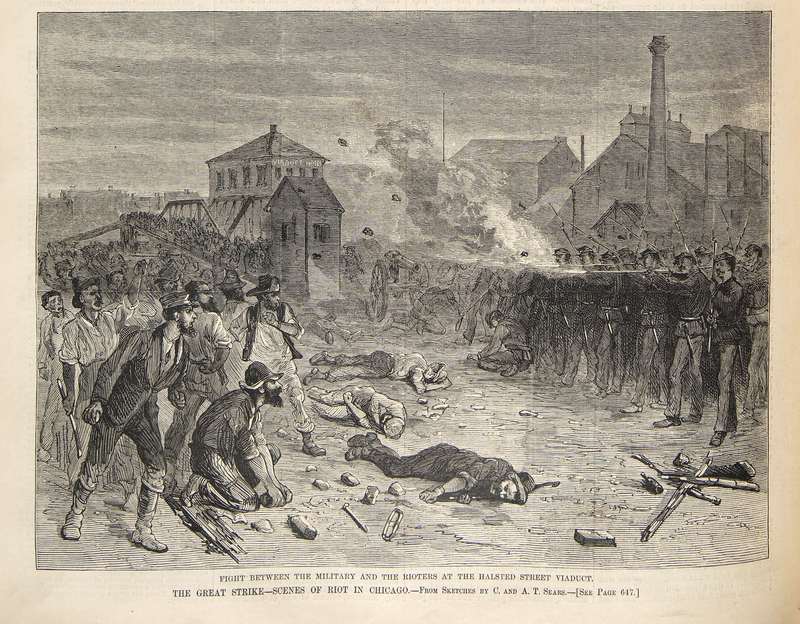

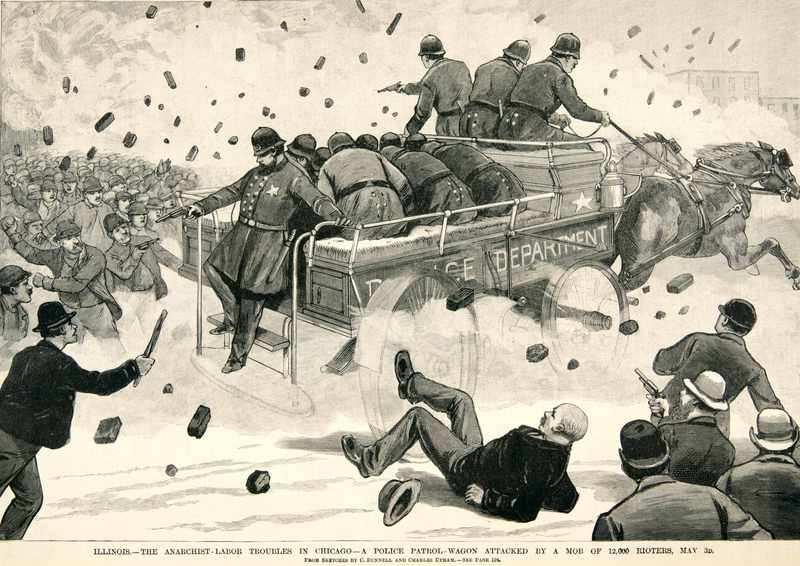

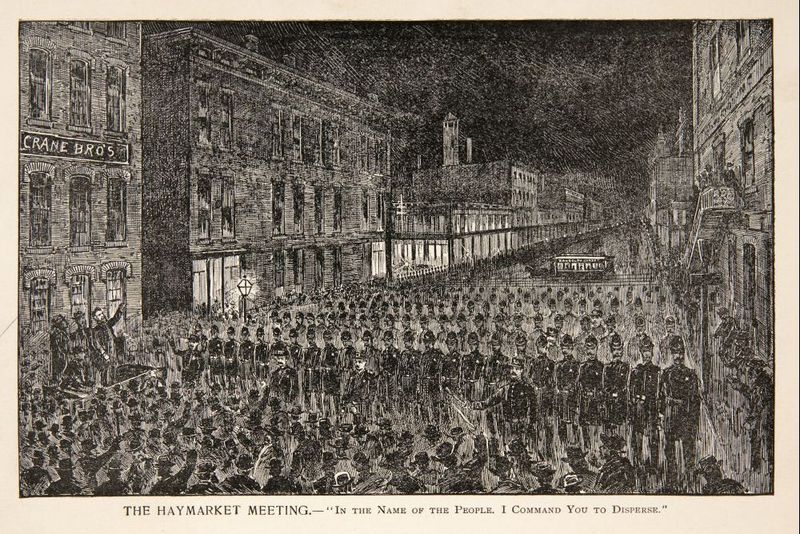

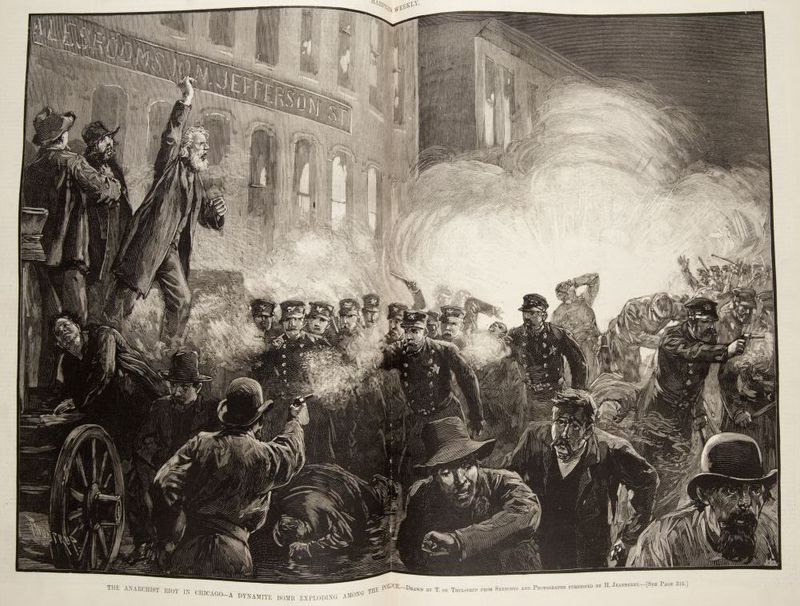

While the popular press anxiously emphasized the radical nature of labor activism, most socialist and anarchists concerned themselves with improving working people's wages and working conditions. Throughout the late 1870s, many labor activists rose to prominence alongside a massive, nationwide outburst of working-class activism. Millions of workers from nearly every trade in nearly every city engaged in tens of thousands of strikes, walkouts, and demonstrations alongside socialists and anarchists to demand improved conditions. Some of these became national in scope. In July of 1877, a walkout by workers of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad in Martinsburg, West Virginia escalated into a nationwide strike against the nation’s major railroads. Across the country, local residents and wage earners from every trade joined with railroad workers to protest the poor pay and low standard of living. In major cities like Chicago, the protests were so intense that state officials had to use federal troops to put down the strike. Some of the images here document the conflicts that erupted in Chicago during the 1877 railroad strike. The remaining illustrations provide glimpses into Chicago’s role in a national movement for the Eight Hour Day in 1886; a demonstration that culminated with the infamous Haymarket Conflict on May 4, 1886.

Drawn from the popular press of the day, the illustrations collected here convey a sense of public opinion at the time. How do they portray industrial relations in the late nineteenth century? How are working people characterized? What is emphasized? What gets overlooked?

Above: Manufacturing Town of Pullman, c. 1880.