The Mound Builders. Newberry Library. View catalog record

1 2021-04-19T17:26:48+00:00 Newberry DIS 09980eb76a145ec4f3814f3b9fb45f381b3d1f02 12 1 Map of Cahokia and surrounding area from 1913 book, The Mound Builders. plain 2021-04-19T17:26:48+00:00 1913 The Newberry makes its collections available for any lawful purpose, commercial or non-commercial, without licensing or permission fees to the library, subject to the following terms and conditions: https://www.newberry.org/rights-and-reproductions Ayer E78.I3 M68 Cahokia (Ill.) Newberry DIS 09980eb76a145ec4f3814f3b9fb45f381b3d1f02This page is referenced by:

-

1

2021-04-19T17:26:48+00:00

Early Indigenous Migration

1

Indigenous societies built expansive trade networks throughout the Midwest since time immemorial.

image_header

2021-04-19T17:26:48+00:00

Above: The Mound Builders, 1913. Newberry Library. View catalog record

Many tribal nations have their own, unique beliefs on how they came to exist in North America. Creation stories are sacred traditions that are rooted not only in oral traditions but in the world around the tribes. Lakes, oceans, trees, rivers, mountains, the sky, canyons and other natural landscapes help to tell the early stories of Indigenous people. These special locations have Native names, relating to their place in creation. For example, many tribes call the continent of North America "Turtle Island," due not only to its resemblance to a large turtle but how some tribal beliefs have a great turtle being the foundation of the world today.

Western science and history have often been at odds with tribal histories in North America. For many generations, non-Native historians and scientists labeled Native communities and cultures from the pre-contact era according to their own ideas and theories. For example, the term "Hopewell culture" or "Hopewellian" is applied to Native peoples in the Midwest from 100 BCE to 300 CE (about two thousand years in the past). The name Hopewell comes from the man who owned the land where important archaeological sites were found from this era, not the name of a tribe. While western science has often separated "Hopewellian" peoples from present-day Indigenous communities, we are the descendants of these same societies -- our nations have been on Turtle Island since time immemorial. Today, federal legislation like the American Indian Religious Freedom Act and the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act acknowledge oral tradition as legitimate evidence and emphasize our ongoing connections to our ancestral lands, the remains of our ancestors, and our historical materials. –Eric Hemenway, Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians, Department of Repatriation, Archives and Records

Indigenous Peoples Before 1300 CE

Prior to European contact, Indigenous peoples flourished across the Midwest as a network of communities rooted in farming and connected by intricate trade routes. Indigenous peoples tended to reside near major waterways and abundantly resourced rivers to support their lifestyle and the complex social networks they were cultivating.

Cut Cassis madagascariensis (Queen Helmet) Shells, Elizabeth Mounds. Illinois State Museum

Cut Cassis madagascariensis (Queen Helmet) Shells, Elizabeth Mounds. Illinois State MuseumLarge marine shells found at one archaeological site were traded in the Midwest from the Atlantic coast or Gulf of Mexico. Cutting and smoothing on the edges of the shells shows they were purposefully modified by people. Although their intended function is unknown, the shells may have been used as drinking vessels. These objects are dated to 25-80 CE and reflect well-established trade and migration networks in Native North America long before European contact. –Illinois State Museum

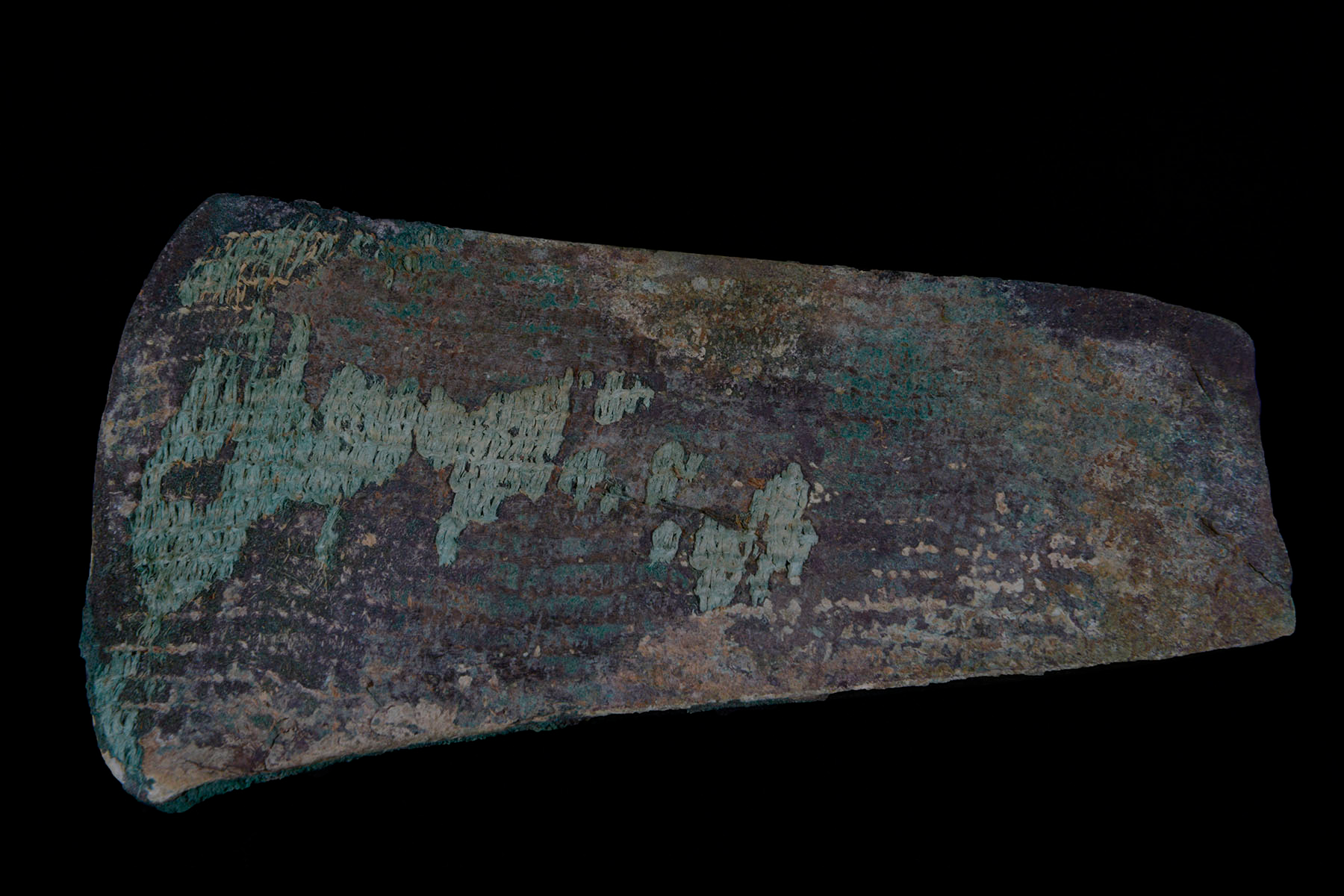

Fabric-Wrapped Copper Adze, Naples-Russell Mound. Illinois State Museum

Fabric-Wrapped Copper Adze, Naples-Russell Mound. Illinois State MuseumCopper adzes and axes were commonly used by Indigenous people in the Midwest, and this particular adze dates to 60-130 CE. The shape of this adze is reminiscent of a woodworking tool, but there is no evidence for use or for attachment to a wooden handle. It was likely an object of ceremonial importance and may have conveyed status or wealth. Copper, a distinctly Midwestern resource in North America, was acquired from the Lake Superior region through trade networks and cold-worked into various forms. –Illinois State Museum

In what is now southwest Illinois, a city now called “Cahokia” was built around A.D. 1050 over the top of the razed remains of an earlier village. It flourished for the next 250 years. A large-scale population movement from the hinterland and resettlement in the sphere of this multiethnic urban center enabled farmers to produce much corn and other food and provided the labor for the construction of public monuments. A ruling elite took responsibility for defense, administration of the center, and ceremonial life. Secondary rulers at Cahokia led neighboring political-ceremonial centers. By 1400 Cahokia’s population had largely dispersed to other Indigenous tribes, but its ideas and rituals continued on in adapted form to influence other communities throughout the Midwest. –Indians of the Midwest, Newberry Library