Moundbuilders

Above: Marching Bears Effigy Mounds, Iowa. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, National Park Service Photo

Ceremonial centers built by American Indians from about 2,200 to 1,600 years ago existed in what is now Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Michigan, as well as elsewhere. The people who built these centers had previously lived more simply as hunters and fisherman and some had begun to domesticate native plants, such as goosefoot, which provided a more reliable food supply. Some communities had begun to make pottery and to bury their dead in or under conical mounds made of earth. Then, a new religion swept through the region, attracting followers who built ceremonial centers along rivers and lakes. They lived in small settlements of kinspeople led by senior family members. The settlements of these believers were oriented to mounds and earthworks, that is, ceremonial centers that were constructed several miles apart along waterways. The believers made pilgrimages to the center nearest them, bringing offerings to spirit beings, who were sources of power, and to accompany burials of some of their deceased relatives.

The religious leaders associated with these ceremonial centers conducted several kinds of ceremonies there. The earthworks, that is, the geometrically shaped embankments that enclosed sacred space and the passageways that connected the embankments, probably reflected the story of creation. When the world first came into being, the life force was manifested in celestial, animal, plant, and human forms. The believers thought that humans could attract power from celestial and animal beings (and possibly from ancestors in the spirit world) to their own purposes, that is, to the restoration of health and prosperity. The symbolism inherent in earthworks represented the powers in the universe as conceived by the builders. Rituals were designed to attract power from the spirit world to renew life and, at the same time, reinforce the faith of the pilgrims.

What remained of the mound centers in the mid-19th century?

Most of the conical mounds at these centers were built over wood structures that served as temples for prayer in general or over crypts. Valuable objects imported from great distances were left as offerings to accompany the prayers. Groups of pilgrims representing kin groups or religious societies buried deceased men and women leaders with collections of offerings and in this way asserted their collective identity.

The burial mounds represented the various social groups that oriented themselves to the center. Such burials remind us of Westminster Abbey in London in which the burials of people of historical importance memorialize the history and achievements of England. The mounds that covered ceremonial chambers were built over several generations by small groups of people carrying earth, sod, sand, and mud in baskets. Probably the religious leaders at the centers fed these volunteers from their stores of food.

Scioto Valley, Surveyed in 1847.

The mound complexes in this river valley in Ohio were surveyed by newspaper man Ephraim Squier and physician Edwin Davis from the town of Chillicothe. Squier and Davis recorded about 200 mounds and 100 enclosures between 1845-47, and they estimated that there were 1,500 enclosures and 10,000 mounds in Ohio. Like the Euro-Americans of their time, Squier and Davis did not believe that these sites could have been built by the ancestors of contemporary Indian people. In the survey of Scioto Valley, in Ross County, they located ten groups of large works with many mounds, including Mound City (E), Hopeton Work (D), and High Bank Works (I). The enclosures are indicated by dark lines and the mounds by dotted lines. Map of a section of twelve miles of the Scioto Valley with its ancient monuments. Ephraim George Squier and Edwin Hamilton Davis, Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, 1848 (Newberry Library, Ayer 36 .M76 S7 1848, pl. 2).

Mound City, Surveyed in 1846 by Squier and Davis

This site had 24 mounds with altars within a large rectangular earthwork about 4 feet high. Ancient works, Ross County Ohio. Ephraim George Squier and Edwin Hamilton Davis, Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, 1848 (Newberry Library, Ayer 36 .M76 S7 1848, pl. 19).

Hopeton Work, Surveyed in 1845 by Squier and Davis

Parallel walls form a passageway to the circular and square enclosures. These walls stretch nearly a half a mile toward the river. This 200-acre site is across the river from Mound City. Archaeologists have found evidence here of ritual activities: clay basins that contained fire and items beautifully crafted from exotic materials. Ephraim George Squier and Edwin Hamilton Davis, Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, 1848 (Newberry Library, Ayer 36 .M76 S7 1848, pl. 17).

High Bank Works, Surveyed in 1846 by Squier and Davis

This site has embankments in the form of circles and an octagon. Built about 1,900 years ago, the ceremonial center also has parallel walls that form a passageway that stretches along two high terraces. Lunar and solar observations could be made from this site. (Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, Pl. 16)

Newark Works, Licking County, Ohio, Surveyed by C. Whittlesey in 1836 and again by Squier and Davis

This ceremonial center was at the conjuncture of the Scioto and Raccoon forks of the Licking River. On a high fertile plain, the ceremonial structures would have been visible from a distance. Parallel walls connected the embankments and led to the river. The circular embankment (F) is identical in size to the circle at Hopeton Work and the one at High Banks Works that is attached to the octagon. These correspondences suggest that the people who built and made pilgrimages to this center shared a religion with those who supported the Scioto Valley centers. Newark was built on a scale that dwarfs many of the famous Old World sites: the Great Pyramid of Egypt would fit within the square enclosure and the Octagon would hold four Roman Colosseums. Ephraim George Squier and Edwin Hamilton Davis, Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, 1848 (Newberry Library, Ayer 36 .M76 S7 1848, pl. 25).

The Serpent, Adams County, Ohio, Surveyed by Squier and Davis, 1846

This effigy mound was built on a hill above a stream about A.D. 1100. The serpent's body conforms to the curve of the hill and winds back, coiling at the tail, a total of 1,348 feet. It is 30 feet at the base and 5 feet high. Used as ritual space, this mound could also be used to observe the path of the sun. Ephraim George Squier and Edwin Hamilton Davis, Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, 1848 (Newberry Library, Ayer 36 .M76 S7 1848, pl. 35).

The "Alligator," Licking County, Ohio, Surveyed by Squire and Davis, 1847

Its construction is dated A.D. 1170-1270. This is actually a water spirit effigy mound. It sits on a high spur over Raccoon Creek. The mound is 250 feet long, 40 feet wide, and 4 feet high (6 feet at the shoulder). The paws and legs were 36 feet long. On the side of the effigy is an elevated altar. In Native belief, this water spirit, though potentially dangerous, could be helpful to humans, especially fishermen and those traveling by water, so offerings were important and this site served as a shrine. Building an effigy probably was an attempt to demonstrate respect for and attract power from a spirit being. Ephraim George Squier and Edwin Hamilton Davis, Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, 1848 (Newberry Library, Ayer 36 .M76 S7 1848, pl. 36).

Map of "Ancient Works" in Wisconsin

Increase Lapham was a land surveyor and cartographer, who many regard as Wisconsin's first scientist. In the 1850s, with support from the American Antiquarian Society, he began systematically documenting the remnants of mound sites. Unlike most Americans of his time, he rejected speculation that the mounds were built by a non-Indian "lost race" or Meso-American people like the Aztecs and, instead, argued that the builders were ancestors of contemporary Native people. On this map the dots indicate the existence of mound groups. Lapham pointed out that the five great river valleys in the state had provided ample resources for the indigenous population. His work was published by the Smithsonian Institution in 1855. Increase Allen Lapham, Antiquities of Wisconsin, 1855 (Newberry Library, Ayer 36 .W8 L3 1855, pl. 1).

Ancient Works, Wisconsin, Surveyed by W. H. Canfield in 1850

These effigy mounds are in the Wisconsin River valley. Note that the bird effigies are all on high ground and that the site contains bird, bear, and water spirit (presumably the linear figures) mounds. These are sites where sacred ceremonies were held. Increase Allen Lapham, Antiquities of Wisconsin, 1855 (Newberry Library, Ayer 36 .W8 L3 1855, pl. 47).

Ancient Works at Aztalan, Wisconsin, Surveyed by I. A. Lapham in 1850

Lapham found the site enclosed on three sides by an embankment as high as five feet that had bastions at intervals. The pyramidal mounds were terraced. He urged that the site be preserved. Increase Allen Lapham, Antiquities of Wisconsin, 1855 (Newberry Library, Ayer 36 .W8 L3 1855, pl. 34).

Most of the conical mounds at these centers were built over wood structures that served as temples for prayer in general or over crypts. Valuable objects imported from great distances were left as offerings to accompany the prayers. Groups of pilgrims representing kin groups or religious societies buried deceased men and women leaders with collections of offerings and in this way asserted their collective identity.

The burial mounds represented the various social groups that oriented themselves to the center. Such burials remind us of Westminster Abbey in London in which the burials of people of historical importance memorialize the history and achievements of England. The mounds that covered ceremonial chambers were built over several generations by small groups of people carrying earth, sod, sand, and mud in baskets. Probably the religious leaders at the centers fed these volunteers from their stores of food.

What did the valuable offerings look like?

About 1,600 years ago, communities throughout the region began to lose interest in the ceremonial centers and focused instead on local rituals. They built only small burial mounds for local mortuary ceremonies. Then, over time the population grew, settlement became denser, and people increasingly relied on the plants they cultivated, including maize or corn imported from the south and altered to thrive in a colder climate. Two new cultural traditions arose, the effigy mound complex in the Upper Mississippi River region and the political-ceremonial centers that emerged in southwest Illinois and spread outward.

Bird Effigy

This figure was made of copper imported from the Lake Superior region 600 miles away. A river pearl was used as the eye of the bird. The bird spirit represented powerful forces from the Above World. It probably was left as an offering by a group of kinspeople or members of a religious society. The bird effigy symbol probably had meaning for the ethnically diverse community of pilgrims who came to the ceremonial center. It was as evocative for them as a cross is for Christians today. This object and the others in this gallery are from Ross County, Ohio and date from A.D. 1-400. Photo courtesy of the Field Museum (#56356, neg. A110028c).

Bird Claw Effigy

Just under 12 inches long, this effigy was cut out of a costly sheet of mica. Mica was obtained from the Appalachian Mountains through direct trade or through exchange with trading partners. Mica work, like copper work, was a highly skilled task. The claw probably symbolized the hunting prowess of a bird of prey. It could have been an offering to the spirits of the Above World in return for success in hunting. Photo courtesy of the Field Museum (neg. A110016c, #110131).

Bird and Fish Effigy Pipe

This small pipe was carved from steatite, a type of stone. Its naturalistic representation of a bird and a fish symbolized both the Above and the Under Worlds. A ritual leader smoked pipes as part of a prayer ceremony in which he tried to communicate with spirit helpers. The tobacco he used could induce a kind of trance to facilitate communication with the spirit world. The fish forms a platform for the bird in the pipe shown here. Platform effigy pipes could be left as offerings. Photo courtesy of the Field Museum (neg. A110058c, #56750).

Atlatl Effigy

These 6 inch long mica cutouts represent an atlatl, which was a special spear-throwing stick with a hook used to propel the spear through the air. The atlatl gave the hunter more power and distance. The effigy could have been left as an offering by a great hunter or his family in order to convey respect to the spirits who aided hunting. Photo courtesy of the Field Museum (neg. A110078c, #56451 and 56150).

Copper Celt Point

This 8 inch long ceremonial axe (celt) represented the authority of a leader, man or woman. It could have been left as an offering by a group of kinspeople. The offering not only was a religious act but also could serve as a symbol of group identity or territorial association with a particular ceremonial center. Stone axes were used for ordinary household tasks. Photo courtesy of the Field Museum (neg. A110041c, #56018).

Obsidian Points

Ross County, OH. AD 1-400. Obsidian came from far west in the Rocky Mountains. These stone points often were left as offerings, arranged in patterns, probably by groups of kinspeople or members of a religious society. These valuable spear points probably represented the importance of hunting and the reliance of humans on the help of animal spirits. Courtesy of the Field Museum (neg. A110019c, #56016, 56052, 56086, 56381, 56773, 56774, 56775, 56780).

Copper Headdress, Ear Spools, Pearls

The headdress, ear spools, and pearl jewelry were worn by leaders. The copper work took great skill and the materials were costly. The headdress took the form of deer antlers. It was made of wood and covered in copper and probably represented the association between hunting ability and leadership. Photo courtesy of the Field Museum (neg. A110046c, #56080, 56091, 56114, 56128, 56200, 56201, 56371, 56751)

Visit an excavation of a site where native people farmed 1,000 years ago

In what is now southwest Illinois, a city now called “Cahokia” was built around A.D. 1050 over the top of the razed remains of an earlier village. It flourished for the next 250 years. A large-scale population movement from the hinterland and resettlement in the sphere of this multiethnic urban center enabled farmers to produce much corn and other food and provided the labor for the construction of public monuments. A ruling elite took responsibility for defense, administration of the center, and ceremonial life. Subordinate to the rulers at Cahokia were secondary ones in neighboring smaller political-ceremonial centers. By 1400 Cahokia’s population had largely dispersed, but its ideas and rituals continued on in adapted form to influence other communities throughout the Midwest.

What did their sacred art look like?

In Wisconsin, a political-ceremonial center (now called Aztalan) was founded by people from the Cahokia tradition about A.D. 1075, and it came into competition or conflict with the people of a widespread effigy mound cultural tradition already there.

Birdman Tablet, Cahokia

This engraved sandstone tablet, about four inches tall, was found on the east side of Monks Mound at Cahokia. The image on the front is human, associated with the Middle World, apparently wearing a raptor mask with a beaked nose, posed in a dancing posture, dressed in falcon or eagle regalia, and holding a feathered wing to one side. The falcon was regarded as a proficient hunter, and by extension, a warrior. On the other side, there is a cross-hatched design, suggesting the pattern on the skin of a snake. The snake was a creature of the Under World and an opponent of sky-world beings, including the Morning Star god-man. This figure may represent Morning Star, who was important in origin stories that persist to this day. In some stories, he was the son of Old Woman (Earth) and Sun, and fought battles on behalf of human beings. He could transform himself into human and animal forms and, after he was killed, came back to life. He offers the power of the regeneration of life to humans. Elite individuals or groups probably led ceremonies designed to attract the help of Morning Star, perhaps even impersonating Birdman, in order to renew life and attract allies and followers. It is not known how this tablet was used or displayed, but the birdman motif is found in many media (copper repousse, engraved shell cups and gorgets, and pottery) at a number of ceremonial sites of this period. Photo by Pete Bostrom, courtesy of Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site.

Crouching Warrior Pipe. Illinois

This figure represents a warrior, or perhaps Morning Star before he revealed himself as a supernatural being. His nudity could represent the unrevealed nature of Morning Star before he began his heroic feats on behalf of humankind. Archaeologists date this object and the others in this gallery to A.D. 1000-1400. Photo courtesy of Dickson Mounds Museum, branch of Illinois State Museum (#800516, MB117).

Man Smoking Frog-Headed Pipe. Cahokia, Illinois

Made of red stone, this pipe probably represented a shaman or an episode in the life of Morning Star, who was able to transform himself into human and animal form. The pipe was used by a ritual leader, probably a member of the elite. Photo courtesy of the Field Museum (2341.82652).

Female Deity Figurine, front. Cahokia, Illinois

This figurine is a cast of the original, which was made of Missouri flint clay (a reddish soft stone), mined west of St. Louis, and carved in Cahokia between A.D. 1050-1150. The woman is hoeing the back of a feline-faced serpent, whose tail splits into two vines bearing squashes. This female spirit being may have been associated with Morning Star and had powers related to the generation of plant life, including corn, as well as human life. Photo courtesy of Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site.

Female Deity Figurine, back. Cahokia, Illinois

On her back is a sacred bundle. The bundle would contain objects associated with her powers, and bundles like this probably were in the care of elite leaders of ceremonies to ensure the earth's cycle of fertility. This theme of fertility associated with female power survives in Native ceremonial life today. Photo courtesy of Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site.

Long Nose God Ornaments, Illinois

This was an ear ornament associated with Cahokia, and possibly with the Morning Star god-man (sometimes called "Red Horn"), who wore human head ear ornaments. Individuals who wore these probably were elite men who gained social and political power by associating themselves with the sacred symbols of Cahokia. Photo courtesy of Dickson Mounds Museum, branch of Illinois State Museum (MB108).

Ceremonial Points. Cahokia, Illinois

These stone points probably were left as offerings. They are expertly crafted. Photo courtesy of Dickson Mounds Museum, branch of Illinois State Museum (#MB075).

Water Serpent Bowl, Illinois

This effigy vessel was made of shell tempered clay. The shell allowed for a thinner and stronger container. The Water Serpent was a powerful spirit being from the Underworld that often opposed various sky deities, including Morning Star. The bowl would have been used in religious ceremonies, not for ordinary household tasks. It was about 8 inches high, 9.6 inches wide, and 11.9 inches long. Photo courtesy of the Field Museum (146.50664).

Underwater Monster (or Panther) Vessel, Illinois

Made of shell tempered clay, this vessel was probably used in ceremonies for feasts or food offerings. The engraved swirls on the sides suggest water and the Lower World. Photo courtesy of Dickson Mounds Museum, branch of Illinois State Museum (#819849, MB028).

Duck Effigy Bowl. Dickson Mounds, Illinois

The duck represents the Above World but also enters the Lower watery world, so it can act to permeate these layers of the cosmos. In the interpretations of some archaeologists, this shell tempered bowl seems to embody the cosmological beliefs of the people who used it. The curvilinear bands suggest an image of the earth floating on water supported by spirit beings that occupy both Upper and Lower Worlds. Photo courtesy of Dickson Mounds Museum, branch of Illinois State Museum (#821481, MB014).

Stone Figurine, Human. Union County, Illinois

This human figure was carved from a rare quartz-like (crystal) material. It may represent an ancestor of one of the groups associated with the political-ceremonial center where it was found or a spirit being. Courtesy of The Field Museum (662.55500)

Who were the elite families and why did they have such influence?

These were precarious times. A warmer climate had stimulated increased reliance on farming, which made communities vulnerable to food shortages when drought or floods occurred. People seemed to have turned to a new religion to ensure crop yields. Besides being religious leaders, the rulers in the political-ceremonial centers were probably also successful warriors who used ritual symbols to link themselves with spirit beings in the Upper and Lower Worlds. These ruling families not only defended and extended the power of their regimes. They also presided over fertility ceremonies to insure good crops. The new political-religious organization had widespread influence. Satellite centers were constructed in what is now Wisconsin, Indiana and other parts of Illinois, and much farther south.

In Wisconsin, a political-ceremonial center (now called Aztalan) was founded by people from the Cahokia tradition about A.D. 1075, and it came into competition or conflict with the people of a widespread effigy mound cultural tradition already there.

Effigy mound centers contained large mounds sculpted in the shape of birds, animals, and creatures of the watery underworld.

Some mounds contained burials, some only prayer-offerings that accompanied ceremonies. Often structures with altars were built on these sites. These complexes marked the territory of kin groups and served as the focus of religious ceremonies to maintain proper relations between humans and spirit beings. The people who built the effigy mounds had basically egalitarian social relationships and relied on wild resources (water fowl, animals, and fish) from wetland areas, as well as gardening. After the end of the mound-building activity about A.D. 1200, the descendants of these people lived on in smaller communities, drawing on knowledge passed from earlier generations and also developing new solutions to the problems they encountered. Their descendants met the Europeans in the early 17th Century.

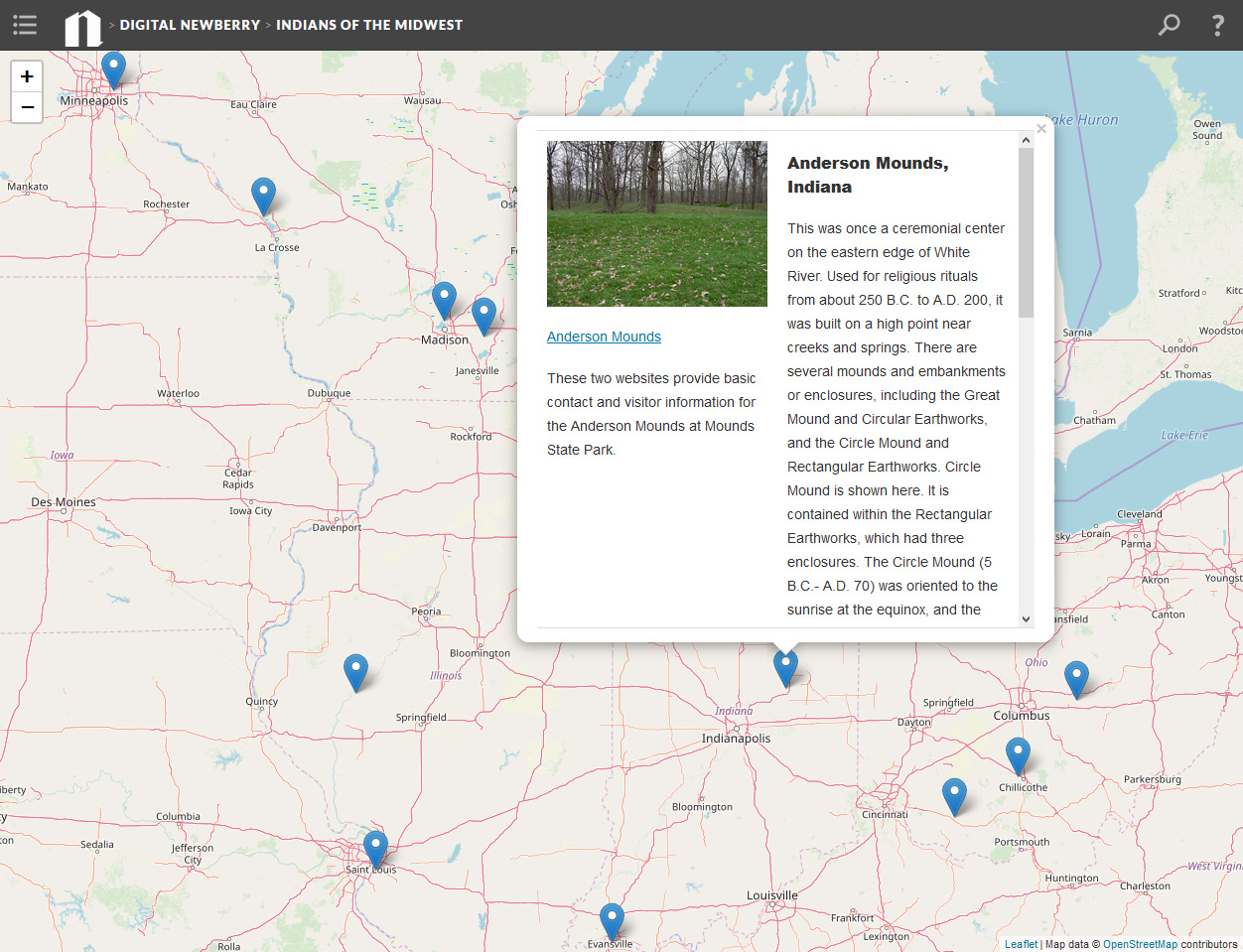

Interactive map: Explore mound complexes in the Midwest

Long Distance Exchange, 100 B.C. – A.D. 500

People living in the ceremonial centers in Ohio interacted with societies hundreds of miles away. Through long-distance travel or group-to-group trade networks, raw materials and finished objects, as well as information (ideas, symbols, inventions, or religious beliefs and values) were exchanged. Galena (lead) came to Ohio from Missouri and northwest Illinois. Grizzly bear teeth and obsidian (a volcanic rock) came from the Rocky Mountains. Chert (a hard stone) came from the Knife River region of North Dakota. Copper came from the Great Lakes region and silver, from eastern Canada. From Mississippi and Alabama, Ohio ceremonial centers received quartz and from the Florida coast, sea shells. Mica came from the Appalachian Mountains and shark teeth from the east coast. Ohio craftspeople transformed the exotic materials into ceremonial objects and personal ornaments that signified prestige. Photo courtesy of Voyageur Media Group, Inc.

Cahokia

The city was built in the Mississippi River floodplain, with easy access to waterways for food and travel. There were over 100 mounds here and a population that ranged between 3,000-15,000 over time. There were four main plazas, smaller ones to the north, east, and west, and the Grand Plaza to the south of Monks Mound. The Grand Plaza, with an area of over 40 acres, was artificially filled and leveled and surrounded by 17 platform and conical mounds. On the tops of the platform mounds were pole and thatch structures that served as homes, council houses, and temples for the elite group. The largest mound, on the north side of the plaza, was Monks Mound, 100 feet high, with four terraces on which there were buildings. In the Grand Plaza, the Cahokians held games that probably had religious dimensions. This central precinct was surrounded by a wall. The drawing also shows the extensive greater community at Cahokia. Outside the center were the smaller houses of non-elites who lived in family compounds associated with small ritual structures (sweat houses) and some elite areas, as well as over 100 mounds. These people worked in the agricultural fields that surrounded Cahokia. Note the Post Circle Monument, or woodhenge, on the far left. Painting by William R. Iseminger, courtesy of Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site

Post Circle Monument at Cahokia

This circle of posts was aligned with the rising sun at certain times of the year. It served as a solar calendar to track the progress of the sun through the year, season by season. Several of these “sun circles,” or “woodhenges,” were built during the occupancy of Cahokia. Photo courtesy of Cahokia Mounds State Historical Site

Aztalan, A.D. 1050-1250

This artist’s reconstruction of a town in what is now southern Wisconsin shows how the non-elite residents lived. These people probably came here from Cahokia. They traded with other peoples in the area. To the southeast of the town were effigy mounds built by a neighboring people who left the area or intermarried with the population in the town. The houses were made of a pole frame covered with clay and the roofs were thatch. People worked outside, cooking and making tools. The children on the lower right are playing a game and adults are carrying food in baskets or doing other work. The clothing was made from plant fiber textiles or hides. They lived on corn and other crops, fish (which they speared at dams they built on the river), deer, and wild rice. In the background is a large platform mound associated with the administrators and ritual leaders furnished by the elite families. Painting by Rob Evans , courtesy of the Kenosha Public Museum, © Rob Evans Murals

Marching Bears Effigy Mounds, Iowa

At Effigy Mounds National Monument on the left bank of the Mississippi near Harpers Ferry is a group of two linear mounds (symbolically associated with water), three bird effigy mounds, and an imposing procession of ten bears that ranged in length from 56-100 feet. The mounds were built between A.D. 600-1150, probably by villages of kinsmen who had a special relationship with the animal spirit represented by a particular mound. The mounds were outlined with lime for this aerial photograph. Photo courtesy of National Park Service

This page has paths:

This page references:

- Ceremonial Points

- Man Smoking Frog-Headed Pipe

- Ancient works on the S. W. 1/4 of the S. W. 1/4 of Section 5. Township 10. Range 7. E.

- Water Serpent Bowl

- Copper Celt Point

- Map of the state of Wisconsin showing the location of ancient works

- Ancient works at Aztalan. View catalog record

- Copper Headdress, Ear Spools, Pearls

- Map of a section of twelve miles of the Scioto Valley with its ancient monuments

- Ancient works, Ross County Ohio

- Crouching Warrior Pipe

- Maps of Hopewell culture Indian mounds in Ohio

- Atlatl Effigy

- Duck Effigy Bowl

- Marching Bears Effigy Mounds, Iowa

- Aztalan, A.D. 1050-1250

- Female Deity Figurine, back

- Newark Works, Licking County, Ohio

- Bird Claw Effigy

- Female Deity Figurine, front

- Obsidian Points

- Bird and Fish Effigy Pipe

- High Bank Works, Ross Co. Ohio

- Post Circle Monument at Cahokia

- Bird Effigy

- Hopeton Work, Ross County, Ohio (four miles north of Chillicothe)

- Stone Figurine, Human

- Birdman Tablet, Cahokia

- Long Distance Exchange, 100 B.C. – A.D. 500

- "The Serpent", (entry 1014), Adams County, Ohio

- Cahokia

- Long Nose God Ornaments

- Underwater Monster (or Panther) Vessel