Winnebago Medicine Lodge

1 2021-04-19T17:19:57+00:00 Newberry DIS 09980eb76a145ec4f3814f3b9fb45f381b3d1f02 8 1 Winnebago Medicine Lodge. Painting by Seth Eastman in Mary H. Eastman, The American Aboriginal Portfolio (Newberry Library, Ayer 250.45 .E2 1853). View catalog record plain 2021-04-19T17:19:57+00:00 Newberry DIS 09980eb76a145ec4f3814f3b9fb45f381b3d1f02This page is referenced by:

-

1

2021-04-19T17:19:57+00:00

American Expansion

1

image_header

2021-04-19T17:19:57+00:00

Above: Winnebago Medicine Lodge. Painting by Seth Eastman in Mary H. Eastman, The American Aboriginal Portfolio (Newberry Library, Ayer 250.45 .E2 1853). View catalog record

After the American Revolution, the U. S. began to sign treaties with Native groups, identified as Tribes, and increasingly tried to take on a dual role of protector and supervisor with sometimes disastrous results.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Indians still lived in villages where several Native groups, European traders, and mixed-ancestry (Métis) people carried on commercial trading locally and internationally, living together peacefully and intermarrying.

How did Indians live in the mid-19th century?

Menominee Village

In the mid-19th century, Menominees lived by hunting, fishing, gardening, harvesting wild rice, and gathering wild plants. Deer still were plentiful but buffalo had left the area. Note the use of a sail, an idea borrowed from Europeans. Their houses were reed mat or bark covered structures, rectangular in summer and dome-shaped in winter. Their villages were governed by a council of the heads of families and people claimed membership in particular families (or clans) through their father's line. Once on the reservation in 1854, these family groups settled in different areas. Menominees still sought spirit helpers, the most powerful of whom were in the Sky World. The Medicine Lodge conducted curing and mortuary rituals. Artist unknown, 1842, courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society.

Dakota Village, ca. 1853

This was a summer village of gable-roofed bark covered houses. In the winter, smaller conical shaped houses were used. The Dakota hunted deer and buffalo until the latter began to disappear in Minnesota in the early 19th century. In the fall and spring, they hunted waterfowl, and fished in the summer with spear and net. The women collected wild rice in the fall. The women tended gardens and the men hunted small animals for their fur. The Dakota had an extensive network of kinspeople on both the mother's and father's side. After they were assigned reservation land in 1853, ties to the local community and payments (from land cessions) became increasingly important. Dakotas made decisions in councils where heads of families deliberated until they all agreed. Dakota individuals sought spirit helpers and often joined religious societies, such as the Medicine Lodge. Painting by Seth Eastman in Mary H. Eastman, The American Aboriginal Portfolio (Newberry Library, Ayer 250.45 .E2 1853).

The Ottawa and Ojibwa at Sault Ste. Marie

Small groups of relatives led by senior family members camped seasonally to take advantage of food resources, including game animals, wild rice, and native plants. Here they are at a fishing camp. They also planted gardens. Individuals belonged to the clans of their fathers. Medicine lodges were held at larger gatherings. Painting by Paul Kane, 1840s, courtesy of Royal Ontario Museum.

Winnebago Medicine Lodge

This painting is a representation of a ceremony of the Grand Medicine Society, which promoted health. Persons who wished to belong to the society sought access to spirit power and apprenticed themselves to members of the society. There were several levels of accomplishment that members had to work to achieve. They sought to learn how to maintain a relationship with spirit helpers and how to heal with plants. Medicine people or Mide also served as spiritual leaders in their communities. This religion was widespread among Great Lakes peoples and continued into the 20th century. Painting by Seth Eastman in Mary H. Eastman, The American Aboriginal Portfolio (Newberry Library, Ayer 250.45 .E2 1853).

Deaf Man's Village, near Peru, Indiana, 1839

Watercolor by George Winter. The leader of this Miami village, Deaf Man, died in 1833. His widow Frances lived here with her daughters and their families. In addition to bark-covered wigwams, they had log cabins, typical of the Miami, who were living in a forested area reserved to them. Deaf Man's family and others also had stables. In the village were 50 or 60 horses, 100 hogs, 17 head of cattle, as well as geese and chickens. There were many small Miami villages in this area, where Miami people received payments from the United States for their land cessions. Miami villages had Indian, Métis, Anglo-American, and African-American residents. Unlike the Ottawa, Dakota, Menominee, and Winnebago, the Miami, who resided on rich farmland, already were surrounded by a large population of settlers. The settlers relied on the Indian trade and sometimes stole stock or other property from the Miami. In 1830, there were 1,154 settlers, and in 1840, 5,480. Courtesy of Tippecanoe County Historical Association.

Camp Scene, Potawatomi, in Indiana, 1837

Watercolor by George Winter. These Potawatomis have left their log cabins to temporarily camp for an event such as a distribution of payments or a ceremony. The woman is grinding up corn to use in the preparation of a meal. The man may have been hunting or working as a messenger. Their garments are made of trade cloth and they wear moccasins. George Winter (1809-76) was born in England and followed his parents to America in 1830. He studied art in New York, then went west to Indiana in 1837, where he worked as a professional painter who produced at least 100 pen and pencil drawings and watercolors, largely of Potawatomi and Miami Indians just prior to their removal from the region. He continued to work as an artist until 1850. Winter's work is recognized for his accuracy of likeness and clothing. Courtesy of Tippecanoe County Historical Association.

Jean Baptiste Brouillette, 1837

Watercolor by George Winter. Of French and Miami ancestry, Brouillette was both a Baptist convert and a healer, who Winter noted had cured a woman of a stab wound. Brouillette was not unusual in his reliance on both old Miami custom and new American alternatives. He was esteemed by his American friends and known as a good orator among the Miami. He wears expensive clothing, including a shawl used as a turban (typical of Miami men) and silver ear bobs. By this time Indian silversmiths made this kind of jewelry. Courtesy of Tippecanoe County Historical Association.

Massaw, 1837

Watercolor by George Winter. Massaw was a woman chief among the Potawatomi, who signed the treaty of 1836. She inherited her position because her father was an important chief. Massaw married an American, Andrew Goslin, who sometimes was employed by the federal government. Very influential among her people, she was quite wealthy and owned an inn. She lived in a large, well-made cabin. She wears a blanket and blouse of broadcloth, many strands of beads, and silver ear bobs. Her clothing is decorated with ribbons and her cape is ornamented with many silver brooches. She wears an expensive blue crepe shawl. Courtesy of Tippecanoe County Historical Association.

The American settlers were not interested in being integrated into this kind of society. They found Indian customs alien, and they were determined to gain control of the land, mineral deposits, and other resources in the area.

The new United States government promoted trade and peaceful relations between Americans and Indians. Officials promised that the Indian tribes would hold the right of possession and use of their lands.

How did Indians use trade goods?

War Club Carved from Wood, with Iron Spike. Sauk and Mesquakie [Fox]

This club also is decorated with braided horse hair and glass beads. Metal obtained from traders largely replaced stone or bone in the manufacture of tools and weapons. Indians repurposed trade goods, for example, making spear and arrow points and knives out of trade kettle scrap. Photo courtesy of the Field Museum (neg. A110951c, 92039).

Quilled Charm Pouch. Sauk and Fox

Porcupine quills were flattened and dyed, then used to embroider designs on hide. This pouch is also decorated with trade beads and wool yarn obtained from traders. A warrior carried objects that symbolized the spirit being on whose help he relied. Photo courtesy of the Field Museum (neg. A110954c, 62514).

Cloth Shoulder Bag. Ojibwa, Wisconsin

This type of bag is called a bandolier. It is decorated with beaded yarn tassels and silk binding. In the mid-18th century through the 19th century, men wore these bandoliers on ceremonial occasions. Bandoliers indicated that a man had social standing. The style probably was in imitation of the bullet pouch carried by British soldiers during the 18th century. At first, Indians used geometrical patterns of beadwork on these bags, but by the 19th century floral patterns prevailed. Silk fabric was a luxury item. Photo courtesy of the Field Museum (neg. A111491c, 15303).

Bandolier Made of Cloth and Decorated with Yarn, Ribbons, and Glass Beads. Ojibwa or Potawatomi, Michigan

This bag has a velvet top, and the beaded floral leaf design is typical of 19th century bandoliers. Photo courtesy of the Field Museum (neg. A111486_1c, 206355).

Woven Yarn Bag. Winnebago, Nebraska

Bags were finger woven from wool from old trade blankets and from wool yarn produced in Europe and in the colonial settlements. Prior to trade with Europeans, women made these bags from buffalo hair wool, basswood fibers, and natural dyes. The designs included the thunderbird and the underwater monster. This bag has a deer design. Photo courtesy of the Field Museum (neg. A144T, 92075).

Wool Bag. Sauk and Fox, Tama, Iowa

This yarn bag also has a deer design. Photo courtesy of the Field Museum (neg. A109622c, 34783).

Woman's Cloth Robe with Ribbon Appliqué. Potawatomi, Wisconsin

Before they relied on trade goods, women made clothing from hide or plant fiber and used porcupine quill embroidery as decoration. After obtaining dress goods, they developed ribbon appliqué decoration to a fine art, and it was used instead of or in conjunction with glass beads. Photo courtesy of the Field Museum (neg. A114177c, 155768).

Moccasins with Ribbon Appliqué and Glass Beads. Potawatomi, Kansas

Moccasins were made of deer hide and were worn every day well into the 20th century. Non-Indians also purchased and wore moccasins in the colonial era. Photo courtesy of the Field Museum neg. A114178c, 155681).

Man's Cloth Shirt with Beaded Floral Design. Fox, Tama, Iowa

Colorful floral designs increasingly were common in the 19th and 20th centuries. Before Europeans arrived, floral designs were used but they were smaller and more stylized. Photo courtesy of the Field Museum (neg. A67T, 111611).

Federal Indian policy stated that land could only be purchased (with money, supplies, and services) and Indian title extinguished through formal treaties. The groups represented by Indian leaders at the treaty councils became identified by the U.S. as tribes or nations, whose rights the U. S. agreed to protect as a trustee would. But the U. S. government could not prevent settlers from steadily encroaching on Indian land. And sometimes Indian groups sold land occupied by other groups.

This eventually led to military resistance by Indian groups in the early 1790s and again in 1810-13 when Tecumseh organized a political movement designed to prevent further land cessions. His defeat led to the sale, often under coercion, of much of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and Michigan during the next two decades. The federal government expected Indians to withdraw or assimilate into American society.

In 1830, Congress passed a law that provided for the removal of all Indian peoples to west of the Mississippi River. The rationale was that by separating the “races” trouble could be prevented. Though the settlers far outnumbered the Indians at this time, the Sauk warrior Black Hawk led a resistance movement in Illinois. Black Hawk was defeated by U.S. troops and their Indian allies. Indian people subsequently chose several strategies. Some agreed to go west to Kansas or Oklahoma, where they had been guaranteed a land base and freedom to live as they chose. Others were force-marched from their homes in what has been called a “trail of tears.”

Where Did They Go?

Pawatomi Emigration, 1838

The Potawatomi in Indiana were affluent compared to most of the settlers, many of whom were envious. The United States pressured the Potawatomi to cede their land in Indiana, and cessions in 1836 involved promises that the Indians would leave Indiana. In 1838, 850 Potawatomi from Yellow River were moved into a camp, held there, then forced to travel west to Kansas. Many died on the way. Their trek became known as the Trail of Death. Winter's drawing shows the Potawatomi on foot and horseback moving toward the Wabash River, while the American citizens watch from the bluffs. Americans moved onto their farms and took over their fields and property after they left. Other Potawatomi groups negotiated for the right to stay in Michigan. Drawing by George Winter, courtesy of Tippecanoe County Historical Association.

Sauk in Oklahoma, 1885

In the photograph, the Sauk chief Pashipaho (standing) and his council are in front of the winter lodge used as a council house. Some Sauk agreed to move from Kansas to Oklahoma in 1867. Most were there by 1869 and the army forcibly removed the others in 1886. In 1890, the land on which the Sauk settled in Oklahoma was allotted and the unallotted acreage, sold. Photo by William S. Prettyman, courtesy of Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma.

Kickapoo Going to Mexico, 1903-05

The Americans forced the Kickapoo west to Missouri in the early 19th century. In 1839 some moved south to Mexico (now Texas), largely for more personal and political freedom. After Texas won independence from Mexico, many Kickapoo went north to Oklahoma. During the Civil War in 1862-65, some left Oklahoma for Mexico, joining Kickapoo already there, living in Coahuila. The Mexican government provided assistance, hoping they would be a buffer against raids by other Indians. In Oklahoma, when the federal government attempted to destroy Kickapoo traditions, a large number migrated south to Mexico (1903-05), seeking freedom and self-rule. In 1905 the Kickapoo moved farther west from Coahuila to Sonora, where they attained reservation land. Oklahoma Kickapoo often visited, particularly to participate in ceremonies. Photo by their agent Martin J. Bentley, courtesy of National Anthropological Archives (neg. 06177300).

Indian Territory reservations

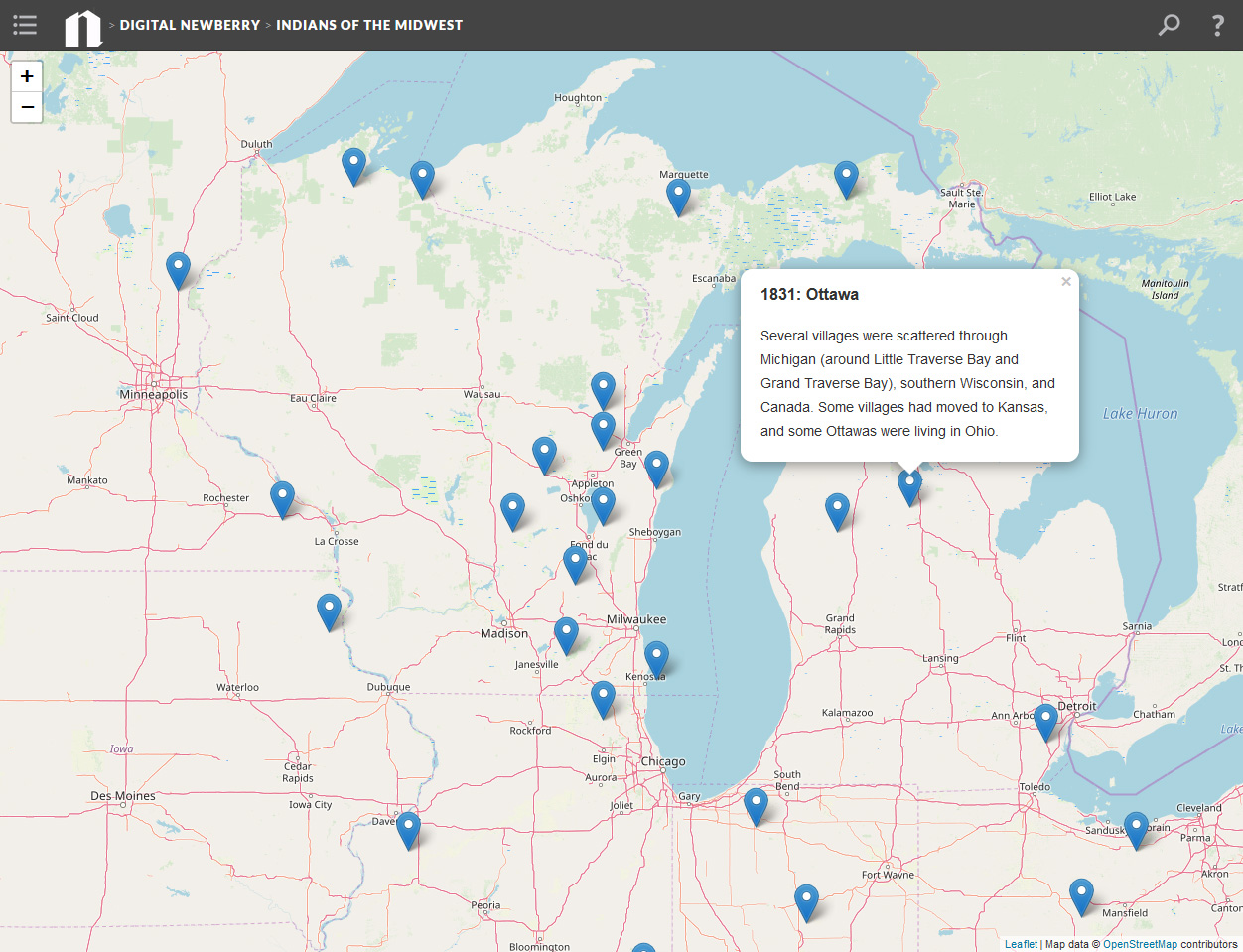

Most of the groups who were forced to leave the Midwest ended up in central and northeast Indian Territory (now Oklahoma): Peoria (Illinois), Ottawa, Wyandot, Shawnee, Seneca (Shawnee allies), Sauk and Fox, Kickapoo, Potawatomi. Groups from the southeastern United States settled in southeast Indian Territory and Indians from the western plains settled in western Indian Territory. Courtesy of Matthew D. Parker, Thomas' Legion: The 69th North Carolina Regiment, thomaslegion.net

A few groups, including the Ojibwas, successfully negotiated for small reservations in their homeland at the time they ceded land. Others fled to Canada.

Some tried to withdraw to underpopulated areas or live unobtrusively among their non-Indian neighbors. In 1862, Dakotas, who were the farthest west, still resided in Minnesota, but lived a life of destitution, in debt to traders and unable to support themselves. After federal officials failed to honor the U. S.’s treaty obligations, some Dakotas attacked neighboring settlers, which led to the federal government’s expulsion of many Indians from Minnesota, including the Ho-Chunk, who had provided troops for the Union during the Civil War.

During the late 19th century, small groups returned from Kansas, Nebraska, and Oklahoma to their homeland in Michigan, Indiana, Wisconsin, and Minnesota, joining Indian communities already there. Some Ho-Chunks obtained homesteads in Wisconsin in 1881 and the federal government guaranteed their title to the land. Some Dakotas returned to Minnesota and eventually received land from the government in the 1880s. Most simply tried to avoid antagonizing the settlers and lived as best they could, hunting and fishing and working for wages.

How did they stay without reservation land?

Frances Slocum and her daughters, 1839

In 1778, when she was about five years old and living on her family’s farm in Pennsylvania colony, Frances was captured by Delawares. She eventually married a Delaware warrior. Later, she married Deaf Man, a Miami warrior, and moved with him after the War of 1812 to the Mississinewa River Valley in Indiana. They had four children, of whom two daughters survived to adulthood. At the time of the removals of Indians in Indiana, she was known as Mo-con-no-qua. She lived in the same manner as other Miami and spoke no English. Apparently, to obtain consideration with respect to removal, she announced her identity as Frances Slocum. Her brother and sister came from Pennsylvania and tried to convince her to leave, but she chose to remain with her Miami family. George Winter painted her portrait at the request of her brother. Her older daughter Cut Finger was married to Jean Brouillette and her younger daughter Yellow Leaf (who turned away from Winter) was a widow. As a Miami, Frances lived a life of relative affluence compared to settlers. In her double cabin, she had beds, a table, chairs, dishes, utensils, blankets, expensive clothing and jewelry. When she revealed her identity, she received national attention. When Americans portrayed her as a pitiful figure held captive for almost seventy years, she generated sympathy and Congress granted her and her family 620 acres of public land in Indiana. She was permitted to draw her payment prescribed by treaty at the nearby Fort Wayne. She named as family members all the people in the village. In this way, a small group of Miami were permitted to remain in Indiana. Another Miami, Francis Godfroy, also received a land grant and subsequently allowed Miami who returned to Indiana from Oklahoma to settle there. Painting by George Winter, courtesy of Tippecanoe Historical Association

Sinisquaw, Potawatomi Woman, with her two children, 1837

Winter painted her at the village of Kee-Wau-Nay, where she lived a relatively affluent life. She was married to an Anglo-American man, Tom Robb, who worked for the federal officials as a messenger. She received $300 a year plus food at the time the treaty payments were made. Sinisquaw converted to Catholicism. She went west with the other Potawatomi emigrants in 1838. Her son (the small child in the portrait) died and her husband died. Subsequently, she returned from the west and settled in a small Potawatomi community in Silver Creek, Michigan. Other small groups of Christian Potawatomi managed to subsist in Michigan and northern Wisconsin. Painting by George Winter, courtesy of Tippecanoe Historical Association.

Leopold Pokagon

After 1830, Potawatomi villages began to cede land and remove west. Most struggled to stay in their homeland. At the 1833 Treaty at Chicago, Potawatomi from northern Wisconsin refused to leave their homes and, in fact, remained. Most of those from southern Wisconsin, Indiana, and Illinois agreed to move west. In Michigan, a group of Potawatomi, led by Pokagon, negotiated successfully to remain. They were Catholic converts. To solidify their position, they purchased land and paid taxes on it, in effect becoming citizens of Michigan. Pokagon held the title to the land on behalf of the others until he died. They pursued their treaty rights throughout the 19th century, obtaining lawyers and sending delegations to Washington. Painting by Van Sanden, 1820s-30s, courtesy of the Center for History, owned and operated by the Northern Indiana Historical Society.

Yellow Thunder in front of a mat-covered wigwam (house), about 1880

He holds a gun stock war club. The Winnebago (Ho-Chunks) were forced to agree to removal by 1838 but not all the Winnebago acquiesced. Yellow Thunder and his followers refused to leave Wisconsin and led a fugitive existence into the 1860s. The federal government made efforts to remove them west of the Mississippi but they persisted in returning to Wisconsin. They attempted to obtain the legal right to stay, issuing appeals to government officials. Yellow Thunder eventually got help to obtain land under the Homestead Act of 1862. In 1881 special legislation provided for 40-acre inalienable homesteads and financial aid to establish farms. They built wigwams and established gardens but continued to practice a subsistence economy dependent on moving from place to place. They clustered around Black River Falls in western Wisconsin and Wittenberg to the east. They lived on homesteads until about 1906. In the early 20th century a number of Winnebago accepted the peyote faith (Native American Church), which coexisted with Christianity and Native religion. Photo by H. H. Bennett, courtesy of National Anthropological Archives (neg. 09830800).

Winnebago Women on a Street in Black River Falls, Wisconsin, 1900-1907

Winnebagos (Ho-Chunks) who refused to emigrate west to Nebraska remained near Black River Falls, as well as near Wittenberg farther east. They subsisted by hunting, gathering, gardening, and fishing and some wage work and they shopped in towns like Black River Falls. Photo courtesy of National Anthropological Archives (neg. BAE GN4348).

In the late 19th century, the U.S. continued to recognize Indian communities on reservations as tribes. The members of several tribes might identify themselves as members of one ethnic group. For example, people ethnically Ojibwa lived on several reservations in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. The U.S. dealt administratively with each reservation as a tribe. In its dealings with Indian communities, the government embarked on an aggressive assimilation program with the help of missionaries.

To further the assimilation program, federal officials assigned individually-owned plots of land (allotments) to Indians and “surplus” reservation land went to non-Indians. Although the title to these plots was guaranteed to be held “in trust” for Indians by the federal government so that the land could not be taxed by the surrounding non-Indian communities, Congress reneged on this promise. Educational institutions for Indian children forcibly discouraged Native language and culture practices. Federal officials declared many Indian customs illegal. Nonetheless, Native peoples resisted abandoning their way of life. Well into the 20th century, they both accepted American agricultural technology and continued to hunt, fish, and gather. They incorporated some aspects of Christianity into Native rituals. And they used formal education as a strategy to pursue Indian rights.

How did Indians cope with assimilation programs?

Political Cartoon, 1890

The performance of the United States as trustee for Indian land and property was a national scandal in the late 19th and the 20th centuries. This cartoon makes the point that the money and resources owed to Indians largely were siphoned off by federal employees and their partners in the corporate world. White Earth reservation will serve as an example. The Ojibwa who settled there had been guaranteed by treaty that they would get help to reorganize their economy. Federal agents pushed commercial agriculture at the expense of lumbering so that the non-Indian lumber interests could remove timber cheaply from the reservation. In 1889 Congress mandated the allotment of the reservation, which meant that Ojibwas born after 1889 would only have land if they inherited it from allottees and they would inherit only a portion of an allotment if there was more than one heir. Land not allotted (and this included the best timber land) was made available for sale at below market prices. Congress recognized the fraud involved but allowed the sales anyway. In 1902 Congress provided for the sale of land of deceased allottees, despite promises in 1889 that the allotments would be inalienable for 25 years. As trustee for the income from Indian land, Congress decided that federal agents would control Indian spending and allowed individuals only ten dollars a month. This was not adequate for their support, so families mortgaged their land to get more money and eventually lost the land. In 1906 the secretary of the interior began to declare some allottees competent to manage their affairs, transferring the trust title to their land into fee status, which meant that the land owner was liable for local property tax. Then competency began to be defined in terms of "degree of Indian blood." The Ojibwa were classed as Full Blood or Mixed Blood, and Mixed Bloods received fee patents on their land. In 1914 the Supreme Court supported this use of "race" as an indicator of competence by ruling that any amount of White ancestry made a person a "Mixed Blood." Ninety percent of the reservation land passed into non-Indian hands and the Ojibwa entered a period of desperate poverty. What money remained in the tribe's account was mismanaged by the federal government. Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection (LC-D4-10865).

Census of Mille Lacs Band of Chippewa, 1849

Drawn by a Chippewa (or Ojibwa) leader, each family is symbolized by the name of the head of the family. The members of this village nearly all belonged to the same clan. There were 108 individuals in 34 families. Some of the names of family heads are: 2, Valley; 4, Shooter; 5, Catfish; 34, Axe. The federal government eventually imposed a Western model of family. Policy mandated that all family members take the name of the male head of household as a surname. Still, individuals continued to identity with their clan. Drawing by Nago-nabe in Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, Historical and Statistical Information, Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States (Newberry Library, Ayer 250 .S3h 1851, v. 2, pl. 54).

Winnebago Girls, Emily Rosh and Cecilia Londrosh, at Carlisle, 1879

Carlisle Indian School was founded in 1879 in an old army barracks in Pennsylvania. It was the first non-reservation school for Indians and became the model for schools elsewhere, both on reservations and off. Indians also attended local schools operated by churches. In the beginning, students had to remain at Carlisle for three-year terms; later, the term was extended to five years. In the summer, the students were sent out to non-Indian homes in the community to work. When students arrived at Carlisle, they were dressed in American-style clothes to change their appearance. They were discouraged from speaking their language. And, they spent half of the day in the classroom learning reading, writing, and arithmetic, and the other half-day working to defray the cost of the school. The boys labored at farming and learning trades, such as shoemaker, and the girls worked cleaning, sewing, and cooking. The goal at Carlisle was to separate the children from their families and communities so as to mold them into "Americans." Officials justified child labor as the best way to teach Indians to "work." Conditions at these schools were such that the death rate among the children was high, and many left in poor health. Most returned to their communities and became reintegrated, some serving as advocates for Indian rights and making use of their ability to speak and write English to help their leaders. In the early 20th century, the federal government began to encourage Indian children to attend local public schools, transferring tribal funds to the states. But Indian children were the victims of discrimination, so reservation schools were the preferred option for Indian parents. Photo courtesy of National Anthropological Archives, (INV. 06829900).

Menominee Medicine Lodge, Shawano, Wisconsin, 1925

Membership in the Medicine Lodge became one form of religious expression and it offered psychological support to its impoverished members well into the mid-20th century. The belief system that underlay Medicine Lodge ritual permeated new religions, such as the Dream or Drum Dance. The Medicine Lodge continued to initiate new members by invitation or through inheritance of a medicine bag (containing herbal medicines). The members of this society played an important role in mortuary ritual, making contact with spirits of the dead to make sure they did not disturb the living. They also cured illness with medicinal plants and by convincing patients of their ability to attract the aid from spirit beings. By affecting the patient’s state of mind, they improved symptoms and the herbal cures often were effective. This postcard is a reproduction of a photo by Truman Ward Ingersoll, 1891, Keshena, Wisconsin. Courtesy of National Anthropological Archives, (INV. BAE GN 609B1).

Potawatomi Prayer board, Wisconsin

Pictographic writing was used to record medicinal formulas and prayers in the Medicine Lodge religion. Native religious rituals coexisted with Christian ones and, in the case of the Winnebago, with peyote ritual, which was introduced through their contacts in Nebraska. Peyote ritual spread to other communities, for example, the Menominee. Photo courtesy of the Field Museum (neg. A111494c, 155764).

Sauk and Fox Ladel

This was probably used in the Medicine Lodge. Note the effigy on the handle. Photo courtesy of the Field Museum (neg. A110952c, 92029).

Winnebago "Powwow," 1907

In the early 20th century, Winnebagos (Ho-Chunks) living in the Black River Falls area began holding Homecoming Dances. Apparently inspired by their contacts with the Winnebago who lived on a reservation in Nebraska, the "war dance" (actually, the Grass Dance, which was a men's society associated with war and war power symbolism) became a feature of these gatherings. There were dances, pony races, ball games, and foot races. They held the dances in a large arbor made of poles with a pine-bough roof. Singers sat around a large drum. The Homecoming was largely attended by Winnebagos from various parts of Wisconsin, as well as Nebraska. At first, non-Indians were not particularly welcome, but in 1908 tradesmen were permitted to sell refreshments, and the next year non-Indians could buy admission. But the Winnebago did not view the event as a "show" for non-Indians. Leaders encouraged the non-Indians to view their contribution as equivalent to the gifts that Winnebagos gave each other at the dance-symbolic of interacting with one's neighbors in a moral way. These dances helped reinforce ethnic group ties and alliances between Indian groups generally. Local dances were held on other reservations in the early 20th century, as well. Photo courtesy of National Anthropological Archives, (INV. BAE GN4412).

Listen to ojibwas explain the impact of the boarding school experience on families

School Experience. Video courtesy of WDSE-Duluth/Superior, MN, 2002. View transcriptInteractive map: Explore tribal locations

Pipe Dance, painting by James Otto Lewis at the Treaty of Prairie du Chien, 1825

Native people tried to establish the same kinds of relationships with the Americans that they had with the Europeans. When greeting them, they attempted to involve them in a calumet ceremony. Here Lewis shows a group of Ojibwas arriving to meet with Americans and other Indian groups. The visitors approach dancing, suggesting war accomplishments. They are received with a pipe that, when smoked, establishes peaceful relations and precipitates gift exchange. According to observers, American officials also were greeted with a pipe ceremony. Painting by James Otto Lewis at the Treaty of Prairie du Chien in James Otto Lewis, North American Aboriginal Port-folio (Newberry Library, Ayer 250.6 .L67 1838).

Open Door

Born in 1774, this Shawnee man’s boyhood name was Noisemaker. He was the younger brother of Tecumseh, a great war chief. His village suffered under the frontier conditions of the colonial period. By 1805, he was an unsuccessful curer and hunter, who had succumbed to alcoholism. Possibly influenced by widespread activity of Shaker preachers and a general religious revival among settlers on the frontier, one day he had a vision in which he received a message from spirit beings: abandon American customs, including the use of alcohol, and return to “traditional” ways. At this point he changed his name to Tens-Kwau-Ta-Waw or Open Door. He began to make converts and the settlers became alarmed. The governor of Indiana Territory, William Henry Harrison, challenged him to prove his powers by making the “sun to stand still.” To the governor’s chagrin, Open Door successfully predicted the eclipse of the sun, and his influence spread throughout the Great Lakes region. Tecumseh, outraged by the trespass on Shawnee land and other affronts, joined with Open Door to build a resistance movement. During 1809-10, he worked to unite all the villages in the region to resist American incursions. His followers were largely young warriors, and, in fact, the established civil chiefs largely opposed his methods. In 1812, Tecumseh allied with the British in a war against the Americans. His followers captured several American forts in Michigan and Illinois, but at the battle on Thames River in 1813, the British fled and Tecumseh with 700 warriors faced 3,200 Americans. Tecumseh was killed and the movement died with him. Open Door survived the war and took refuge in Canada. Eventually, he returned to the United States and settled on a reservation in Kansas, where he died in 1836. Thomas Loraine McKenney and James Hall, History of the Indian Tribes of North America (Newberry Library, Ayer 249 .M2 1848, v. 1).

Battle of the Thames (October 5, 1813)

This lithograph based on a painting by William Emmons shows Tecumseh’s death in battle. He was born in 1768 in Old Piqua (in what is now Ohio). His father was a Shawnee war chief and his mother, a Creek, from a region south of Ohio. He lived on the frontier during difficult times. Trespassing Americans killed his father when he was a teenager. In 1790 the American army marched into the Ohio River country and attacked Shawnees and Miamis. American settlers hated their Indian neighbors because many had helped the British during the Revolutionary War. In 1794 Indian resistance collapsed, but Tecumseh, who had fought the Americans, refused to attend the peace council at Greenville in 1795. By the age of 27, he was a respected warrior, whose name meant “panther lying in wait.” Tecumseh began to organize a new resistance movement, drawing on the influence of his brother, the prophet Open Door. His hope was to organize the Indian Country into a political union that could resist American domination. He recruited young warriors from most of the villages in the Great Lakes area. By 1809-10, he had 1,000 warriors but there were 20,000 Americans in southern Indiana alone. His British allies in the War of 1812 failed to give him the promised support, and when he was killed at the battle on the Thames, the movement lost support. Courtesy of Library and Archives Canada, W. H. Coverdale Collection of Canadiana (Acc. No. 1970-188-997).

Black Hawk, Portrait by James Otto Lewis, 1838

Black Hawk (1767-1838) was born in the great village of the Sauk on the Mississippi River in Illinois. This was a huge town of almost 7,000 Sauk and their Fox allies, with lush gardens and long bark-covered houses. As a youth he encountered his spirit helper, the sparrow hawk, in a vision and took his name from this experience. As a young man, he was a respected warrior who led men into battle. In 1804, American soldiers arrived in St. Louis, as did settlers who moved illegally onto Sauk lands. In a quarrel, some Sauk killed three settlers and several Sauk went to St. Louis to pay damages as was their custom. But the United States demanded the cession of land. Although the individuals in St. Louis did not have authority to treat on behalf of all the Sauk and although they were under duress, the United States argued that the Sauk ceded all their land for $600. The Sauk believed that they had granted permission to Americans to live on the land at the same time they continued to hunt, farm, and fish there. American officials reassured them in subsequent years that they could stay. The continued arrival of settlers alarmed Black Hawk and he supported Tecumseh in 1812. The next year the Americans began pressuring the Sauk to move west of the Mississippi River. Periodically, Americans harrassed the Sauk villages. In 1827 the United States insisted that the Sauk leave. Black Hawk refused even as settlers moved into his village and took over his fields. The United States began selling the land to settlers, 150,000 of whom moved into Illinois. In 1831 Black Hawk was influenced by White Cloud, a Winnebago prophet, who assured him that an armed resistance would be successful. In 1832, Black Hawk had attracted more than 400 warriors from several groups struggling to remain in their homes. The army and local militia pursued Black Hawk’s forces and rejected his offer to surrender. Troops caught his followers as they were crossing the Mississippi toward Iowa and slaughtered a large number of men, women, and children. Black Hawk surrendered and was taken east, where he was sent on a tour designed to impress on him that resistance to the United States was futile. He returned to his people in Iowa and died at the age of 71. Painting by James Otto Lewis in James Otto Lewis, North American Aboriginal Port-folio (Newberry Library, Ayer 250.6 .L67 1838, no. 1, pl. 3).

Land Cessions

This map shows the progressive loss of land as Menominee and other tribes ceded land in Wisconsin in treaty councils. In the Menominee case, they made a major cession in 1831 when they agreed that “New York Indians” could occupy some land (section 158) southwest of Green Bay and they ceded a large section of land (section 160) to the United States, reserving land for themselves bounded by the Fox and Wolf Rivers and Lake Winnebago. In 1836, Wisconsin Territory was organized and the Menominees experienced more pressure to cede land. At the Treaty of Cedars, in return for 20 years of payments and gifts (and the payment of debts to traders), they ceded two sections (219 and 220). In 1848, when Wisconsin became a state, the governor was determined to remove Indians, in large part to satisfy timber interests. The Menominee again were pressured. They agreed to cede their remaining lands in Wisconsin (section 271), but worked relentlessly to convince the President to allow them a reservation in their homeland. President Millard Fillmore responded to petitions from Catholic missionaries and others, eventually establishing a small reservation for Menominee on Wolf River. Charles C. Royce, Indian Land Cessions in the United States (Newberry Library, Ayer 301 .A2 1896-97, pt. 2, v. 18, map 64).

New York Indians from Wisconsin (probably Oneida and Stockbridge-Munsee) are sworn into military service to fight for the Union Army

135 Oneidas (10% of the population) volunteered and only 55 returned. Men enlisted from other tribes as well. Indians from the Midwest fought for the United States in all the wars subsequent to the Civil War. Many Indians saw military service as a way to reinforce their political alliance with Americans and protect their communities. Courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society.

Gus Sharlow, World War I Veteran

Sharlow was an Ojibwa from Hayward, Wisconsin. The United States entered World War I in 1917. Some 16,000 Indians served in the military forces. Afterwards, the contribution of these soldiers led to public pressure to grant Indian veterans the right to vote. Eventually in 1924 Congress passed the Indian Citizenship Act, which provided Indians with U. S. citizenship. Tribal citizenship could be held simultaneously with U. S. citizenship. At the same time that military service fostered appreciation among the American public, it helped reenergize religious ceremonies and “war dancing” in Indian communities. Military service brought a man prestige and elicited great support from his community. Photo courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society.

Ojibwa Dream Dance Drum

In 1876, Wananikwe, a Dakota woman, had a vision of a new religion. This prophet took the religion, the Drum Dance, to the Minnesota Ojibwa. It spread eastward, including to the Menominee community in Wisconsin. This religion incorporated Christianity along with aboriginal elements in ways culturally compatible with local practices. Membership in the congregations was less difficult than in the Medicine Lodge, so the Drum (or Dream) Dance gained many practitioners. Through visions, the participants tried to contact spirit helpers to petition for help. The congregation also encouraged social cooperation. The drum was sacred, as it represented a spirit being. The faithful brought gifts to the spirit helper in return for aid with 19th and 20th century problems. The drum in this photo was photographed by A.E. Jenks in 1899 at Lac Courte Oreilles. Photo courtesy of National Anthropological Archives (neg. no. 49,399).

-

1

2021-04-19T17:20:02+00:00

Ownership

1

image_header

2021-04-19T17:20:02+00:00

Above: Meda meeting in secret, opening their medicine bundles. Drawing by Seth Eastman in Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, Historical and Statistical Information, Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States (Newberry Library, Ayer 250 .S3h 1851, v. 5, pl. 5). View catalog record

Native people in the Great Lakes area recognized individually-owned property. Women and men owned their own tools, clothing, ornaments, and any gifts of property they received. Ojibwa husbands and wives owned property separately but lent their possessions to each other. These ideas about gender and property contrasted with those in colonial and early 19th century America, where married women could not own property. Native children owned their toys and clothing, so parents did not have control over their children’s property.

What kind of property did they own?

Rush Mat, Sauk and Fox

Women made and owned these mats. This one is woven with nettle fiber cord and dyed with botanical substances from the forest. Rows of deer form the design. Photo courtesy of the Field Museum (#34989, neg. A110957c).

Woman Weaving Rush Mat

Shown here is Mrs. Gurneau at Red Lake, Minnesota making a floor mat. Women could work on these mats only early in the morning or evening when the air was moist so the reeds would not dry out and become brittle. Mrs. Gurneau made the bark frame herself. Frances Densmore, Chippewa Customs, 1929 (Newberry Library, Ayer 301 .A5 v. 86, pl. 1).

Woman's Pipe

Women's pipes were made of black stone, and men's of red stone. The stem was wood. This pipe is for everyday smoking (bark and/or tobacco) and is about 7 inches long. Pipes for formal use had longer stems, and ceremonial pipe stems could be 3 feet long, and they were elaborately decorated. Frances Densmore, Chippewa Customs, 1929 (Newberry Library, Ayer 301 .A5 v. 86, pl. 52a).

Knife case, Dakota Sioux

Men owned their knives and the cases (made by women and given to men). This case is decorated with bird quills. It is almost 10 inches long and a little over 3 inches wide at the top. It was collected by Frank Blackwell Mayer at the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux in 1851. Photo courtesy of the Field Museum (#12976, neg. A110272_Ac).

Bow and Bird Arrow

Men made and owned their bows and several different kinds of arrows, depending on the game they were hunting. The bird arrow was made of hickory and was used for hunting birds. Paul Radin, The Winnebago Tribe; 37th Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 1915-16 (Newberry Library, Ayer 301 .A2, pg. 118, pl. 31).

Infant with Ornamented Cradle Board

Women made cradle pouches for babies before they were born, and the baby's navel cord was placed in a small bag and tied to the cradle, as were small toys, including strings of beads, little bones, shells, birchbark cones, and feathers. Men usually made the frame. The mother's in-laws brought her gifts and the father gave a feast for a spirit being as thanks for the healthy child. Paul Radin, The Winnebago Tribe; 37th Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 1915-16 (Newberry Library, Ayer 301 .A2, pg. 121, pl. 42a).

Individuals also owned intangible property, often associated with power received in a dream vision. Youths fasted in isolation for a vision in which a spirit helper granted them various powers (in hunting, war, and curing, for example). Ojibwa girls also had dreams in which they acquired power. Associated with the power were objects (for example, a medicine bag), names, and songs given by the spirit helper that symbolized the power of the vision. The power was not effective without the supernatural connection with the spirit. And the owner had to feed the guardian spirit with tobacco and food to maintain the relationship.

Members of the Medicine Lodge (“meda” or “mide”) acquired a medicine bag and other objects upon initiation. They could pass the bag on to a new initiate (for a fee) or dispose of it whatever way they chose.

Some property was owned not by individuals but by groups. Individual clan members served as custodians of clan-owned medicine bundles. Among the Ojibwas, the Dream Dance ritual was owned by groups (possibly residential or family groups or villages). Sometimes, Ojibwa villages owned dances they purchased from other tribes: the village leader was the custodian of the dance.

Land and the resources on it were not “owned” by either groups or individuals. People had “use-rights” to places where they would garden, fish, harvest rice and berries, and tap for sugar. As long as they used these resources, they had a right to them. Villages that had use-rights in a territory permitted others to hunt, fish, and gather there. Even after Americans imposed allotments and legal title to land, the resources on the land continued to be viewed by Indians as associated with use-rights.

Native people valued property as a means of strengthening social bonds. It was never to be accumulated by individuals or groups while other community members went without. Food was always shared with kin and needy members of the community. When a man killed a deer, he shared the meat by hosting a feast. After a group hunt, the meat was divided among the hunters and their families. Community feasts were frequently held when food was harvested or spirit helpers honored. Clans regularly feasted each other. Tools, clothing, and other items were given to others as gifts, sometimes to reinforce friendship and sometimes to meet a kinship obligation.

Obligations to relatives continued after death. Family members dressed the corpse in fine clothing and jewelry and often buried his or her prized possessions with the deceased. Above the grave, many groups erected a grave house with a ledge where they brought tobacco and food to feed the soul of the deceased person for his or her four-day journey to the Afterlife. Property that might be useful for the journey might be left at the grave or buried: weapons, tools, moccasins, cooking and eating utensils. Food was brought to the grave subsequent to these mortuary rituals, as well. These gifts could be used in the Afterlife by the deceased to establish good relationships there. The bereaved would be helped to go on with their lives by annual or periodic attention from others, including gift-giving.

Learn more about mortuary ritual

Grave Post of Shing-Gaa-Ba-Wasin (The Image Stone), Ojibwa Warrior

On his carved post is his clan symbol, the Crane, upside down to indicate death. On the right are six horizontal "marks of honor" that indicate battles in which he distinguished himself. On the left, three horizontal bars represent three treaty councils in which he participated. Grave posts with an inverted clan symbol continued in use well into the latter half of the 20th century. Drawing by Seth Eastman in Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, Historical and Statistical Information, Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States (Newberry Library, Ayer 250 .S3h 1851, v. 1, pl. 50, no. 4).

Feeding the Dead

Scaffold burials were used, as well as interment, until lumber became available for grave houses. Relatives brought food to the soul (ghost or spirit) of the deceased. The ghost ate the spiritual essence of the food, and members of the community could take the food to eat. Food was offered each day during a four-day mortuary ritual, and families usually would bring food periodically for some time afterwards to maintain good relations with the soul of the deceased. Feeding the dead was common to virtually all the Great Lakes Native communities. Drawing by Seth Eastman in Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, Historical and Statistical Information, Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States (Newberry Library, Ayer 250 .S3h 1851, v. 1, pl. 3).

Ojibwa Grave Houses, 1925

This cemetery at Leech Lake shows the ledge on the grave house where food was placed, the grave posts, and some property left for the deceased. Before the 19th century, bodies were buried wrapped in bark and covered with a small mound or bark, or the body was put on a scaffold or in a log enclosure. The grave post with inverted clan symbol was placed by the grave. When lumber became available in the 19th century, grave houses with ledges for food offerings were commonly built over interments. Even Christian converts had this kind of burial. Photo by Huron Smith, courtesy of Milwaukee Public Museum.

Today, feasting and gift-giving are important rituals in Native communities. They serve to strengthen the bonds between living people and between the living and the dead. For example, the Ottawa hold “Ghost Suppers” once a year at several settlements. People come together to feast and honor their deceased relatives. At community powwows throughout the Midwest, families give away property to visitors to honor relatives participating in the powwow and to establish friendly relations with non-members of the community. Food also is often distributed to these visitors. And helping others with food and other kinds of economic assistance still is a central value in Indian communities.

Read the instructions a Ho-Chunk elder gave a youth about generosity. Note how generosity is supernaturally sanctioned.

My son, when you keep house, should anyone enter your home, no matter who it is, be sure to offer him whatever you have in the house. Any food that you withhold at such time will most assuredly become a source of death to you. . . . If you see an old, helpless person, help him with whatever you possess. Should you happen to possess a home and you take him there, he might suddenly say abusive things about you during the middle of the meal. You will be strengthened by such words. This same traveler may, on the contrary, give you something that he carries under his arms and which he treasures very highly. If it is an object without a stem [medicine plant], keep it to protect your home. If you thus keep it within your house, your house will never be molested by any bad spirits. Nothing will be able to enter your house unexpectedly. Thus you will live. From Paul Radin, The Winnebago, 37th Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 1915-16, p. 170.

Bear Medicine Cloth

A man from Mille Lacs owned this medicine (the power to cure), which he received when he obtained a spirit helper in a vision. The bear spirit was his helper and he kept a representative drawing on a piece of cloth. The man’s wife became very ill, so he spread the cloth over her so that the strength of his bear spirit helper would transfer to her. She improved, then he put the cloth on the wall above her head until she recovered fully. This kind of personal medicine was owned by both men and women among the Ojibwa. Frances Densmore, Chippewa Customs, 1929 (Newberry Library, Ayer 301 .A5 v. 86, pg. 83, pl. 32a).

Winnebago Mide at Medicine Lodge

Here, the Mide or Meda, who cure patients and assist the souls of the dead in their journey to the Afterlife, are using their medicine bags as they conduct ceremonies in the Lodge. Painting by Seth Eastman in Mary H. Eastman, The American Aboriginal Portfolio (Newberry Library, Ayer 250.45 .E2 1853).

Meda meeting in secret, opening their medicine bundles

Each man owned his bundle. His right to do so was purchased when he was initiated into the Medicine Lodge. Drawing by Seth Eastman in Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, Historical and Statistical Information, Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States (Newberry Library, Ayer 250 .S3h 1851, v. 5, pl. 5).

Ho-Chunk Bear Clan Police, Black River Falls, Wisconsin, ca. 1900

These members of the Bear Clan are holding batons of authority, which were clan property. The Bear Clan has always been responsible for keeping order. They supervised hunts and camp movements, dealt with wrongdoers, and generally policed public gatherings. Each Ho-Chuck clan owned a war bundle (formerly owned by families and used for success in war, then gradually associated with the clan and used to pray for success in life generally). The Bear Clan owned a war bundle, war clubs, two crooks used in battle, and batons of authority. There are twelve clans and, today, seven or eight active war bundles. Photo by Charles Van Schaick, courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society.

Ojibwa Dream Dance Drum, 1899

This is one of three drums at this ceremony at Lac Courte Oreilles. The drums were owned by residential communities on the reservation. Ojibwa groups transferred drums to groups from other tribes, including the Menominee, receiving gifts in return. The Menominees organized dream dance societies, each of which had a drum. The keeper of the society’s drum had to be qualified in the eyes of the society members. Courtesy of National Anthropological Archives (NAA INV 00255400).

Treaty of 1837

The Ojibwa groups who signed the treaty at St. Peters on July 29 insisted on retaining the right to hunt, fish, and gather throughout the area they ceded in Wisconsin and Minnesota. From Ratified Indian Treaties, National Archives Microfilm Publication (Newberry Library, Microfilm 152, roll 8).