Reseeding Wild Rice on Little Traverse Bay Reservation

1 2021-04-19T17:20:06+00:00 Newberry DIS 09980eb76a145ec4f3814f3b9fb45f381b3d1f02 8 1 Reseeding Wild Rice on Little Traverse Bay Reservation. Photo courtesy of Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC) plain 2021-04-19T17:20:06+00:00 Newberry DIS 09980eb76a145ec4f3814f3b9fb45f381b3d1f02This page is referenced by:

-

1

2021-04-19T17:20:00+00:00

Treaty Rights

1

image_header

2021-04-19T17:20:00+00:00

Above: Treaty of Traverse des Sioux, 1851. Painting by Frank Blackwell Mayer, 1885, courtesy of Minnesota Historical Society

In the aftermath of social changes generated by the Civil Rights movement in the United States, Native Americans were able to push more vigorously for redress of their grievances. One of the issues was the states’ violation of the treaty rights of Indians to hunt, fish and gather in the lands they ceded to the U. S. The federal government had not enforced their part of these treaty agreements. Tribes brought suit to reaffirm these rights: Lac Courte Orielles v. Voigt was only one such case. In the LCO v. Voigt case, the federal courts ruled in 1983 that the signatory tribes to the 1837 and 1842 treaties had never ceded the right to hunt, fish and gather on lands in northern Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Michigan.

Why did the court rule the way it did?

Excerpts from Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians v. Voigt C.A. Wis., 1983. United States Court of Appeals, Seventh Circuit.

Actions were brought involving property interests and hunting and fishing rights of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians in northern Wisconsin. James E. Doyle, of the United States District Court for the Western District of Wisconsin, granted defendants’ motion for summary judgment, and the plaintiffs appealed.

Facts

The LCO band was one of many bands of Chippewa Indians that lived in areas of northern Wisconsin, the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and northeastern Minnesota. Together with several other bands, the LCO band was referred to as “Lake Superior Chippewas.” The Chippewa [Ojibwa] bands subsisted mainly by hunting, fishing, trapping, harvesting wild rice, making maple sugar, and engaging in various gathering activities. In 1837, Wisconsin Territorial Governor Henry Dodge was authorized to negotiate a treaty with the Chippewas for the purchase of land in northern Wisconsin, just south of the Lake Superior basin. A treaty council was held. According to the notes of the secretary of the council, Commissioner Dodge told the assembled Indian chiefs in July 1837 that the Government wished to buy a portion of their land that was barren of game and not suited for agriculture. The Indians responded that they wanted to be able to continue their gathering and hunting activities on the lands, that they wished annuities [payments] for sixty years, after which their grandchildren could negotiate for themselves. Commissioner Dodge replied, in part: “I will make known to your Great Father [the president], your request to be permitted to make sugar, on the lands; and you will be allowed, during his pleasure, to hunt and fish on them.” Article 5 of the Treaty states: The privilege of hunting, fishing and gathering the wild rice, upon the lands, the rivers and the lakes included in the territory ceded, is guaranteed to the Indians during the pleasure of the President of the United States. In 1841, Congress appropriated $5,000 for the expenses of negotiating a treaty to extinguish Indian title to lands in Michigan, a portion of which was held by the Chippewa bands. The 1842 treaty included a cession of land north of that ceded in 1837. Article II of the Treaty of 1842 stated: The Indians stipulate for the right of hunting on the ceded territory, with the other usual privileges of occupancy, until required to remove by the President of the United States. The President issued an executive order on February 6, 1850. This Order stated in relevant part: The privileges granted temporarily to the Chippewa Indians by the fifth article of the treaty made with them on the 29 th of July 1837 and by the second article of the treaty with them of October 4 th, 1842, are hereby revoked and all of the said Indians remaining on the lands ceded as aforesaid, are required to remove to their unceded lands. On April 5, 1852, a group of Chiefs went to Washington to see the President. Chief Buffalo beseeched the President and his agents to honor the Treaty of 1842 as the Indians understood it. President Fillmore told the delegation that he would countermand the Removal Order of 1850. The Treaty of LaPointe was concluded September 30, 1854. It provided that the Lake Superior Chippewas living in Minnesota ceded their territory to the United States. These Minnesota bands were granted usufructuary [use] rights on the ceded land pursuant to Article 11. Article 2 specified that the United States agreed to withhold from sale, for the use of the Chippewas, certain described tracts of land. One was set aside for the LCO band. Even after the reservation boundaries were settled, many Chippewa Indians continued to roam throughout the ceded area, engaging in their traditional pursuits.

The Law

The Supreme Court has held that Indian treaties must be construed as the Indians understood them. “Treaty-recognized title” is a term that refers to Congressional recognition of a tribe’s right permanently to occupy land. It constitutes a legal interest in the land and, therefore, could be extinguished only upon the payment of compensation. Treaty-recognized rights of use do not necessarily require that the tribe have title to the land. It is perfectly consistent with the basic tenets of property law that one may enjoy a right of use that is limited in duration. The fact that it is so limited makes it no less of a legal right. Abrogation of such rights should not be found without compelling evidence that such an extinguishment was intended. A treaty is essentially a contract between two sovereign powers. If the United States promised a tribe that it would enjoy certain rights either for a specified period or until a specified event or events occurred, those rights were legally enforceable by the Indians.

Summary of Findings

Nothing in the record compels the conclusion that the LCO band understood the Treaty of 1854 as abrogating their treaty-recognized usufructuary rights. Similarly, nothing compels the conclusion that the Government intended such an extinguishment. The sequence of events following the attempted removal of the Chippewas in 1850 would logically have confirmed their belief that removal and extinguishment of usufructuary activities could be avoided if they did not harass white settlers. As to the intentions of the Government, the Removal Order of 1850 referred specifically to the extinguishment of usufructuary rights as well as ordering removal of the Chippewas. This suggests that the Government knew the Indians did not understand the exercise of usufructuary rights to be dependent on their permanent occupancy of the land. The rationale employed by Judge Doyle at best supports the implied abrogation of the LCO band’s usufructuary rights pursuant to the 1854 treaty. The extinguishments of treaty-recognized rights by subsequent Congressional act will be found only if it is clear that such a termination was intended. The evidence supporting relinquishment or abrogation in the instant case fails to meet that standard.

Conclusion

The LCO band enjoyed treaty-recognized usufructuary [use] rights pursuant to the Treaties of 1837 and 1842. The Removal Order of 1850 did not abrogate those rights because the Order was invalid. These aspects of our holding are consistent with the conclusions reached by Judge Doyle. We disagree with his conclusion that the Treaty of 1854 represented either a release or extinguishment of the LCO’s usufructuary rights. At most, the structure of the treaty and the circumstances surrounding its enactment imply that such an abrogation was intended. Treaty-recognized rights cannot, however, be abrogated by implication. The LCO’s rights to use the ceded lands remain in force. The case is remanded to the district judge with instructions to enter judgment for the LCO band on that aspect of the case and for further consideration as to the permissible scope of State regulation over the LCO’s exercise of their usufructuary rights.

Listen to an Ojibwa fisherman talk about the struggle for fishing rights

Fishing Rights. Video courtesy of WDSE-Duluth/Superior, MN, 2002. View transcriptThe state of Wisconsin petitioned the U. S. Supreme Court to review the 1983 Court of Appeals decision, but the court found no grounds to do so. After the 1983 ruling, five other Ojibwa bands in Wisconsin joined the lawsuit and proceeded with the case in the District Court to determine issues relating to regulation. In 1987 Federal Judge Barbara Crabb ruled that the tribes possess the authority to regulate their members and that effective tribal self-regulation precludes state regulation.

How did perspectives on “heritage” and its relationship to fishing rights differ between many Native and non-Native people?

Here is one Ojibwa man’s perspective

Speech of Ojibwa Activist

I’m eagle clan and I come from Waswaaganing

what other Indians call Lac du Flambeau,

a long time ago it was called Waswaaganing

Waswaaganing literally translates

“Waswa,” means spearing, spearing with a torch.

“ganing,” the locator, the place where it happens.

Waswaaganing, the place where they fish with a torch.

But spearing has been going on at Lac du Flambeau for many, many

Hundreds of years, a long time before the non-Indians showed up.I’m a teacher at the Lac du Flambeau grade school

I teach culture. I tell Winaboozhoo stories.

I do many things that are really not in the school curriculum . . .

I teach the Ojibwe philosophy; I try to teach the Ojibwe philosophy.

Respect, love, humility, kindness,

Through stories, legends.

I use cedar, tobacco, sage, sweetgrass.

It’s being done more and more on the reservations now. Because

What they call

Neesh-wa-swi’ish-ko-day-kawn’ literally translated means the Seven

Fires Prophecy.

It talks about this time, this era that we’re in.Before I get into that I want to tell you about the spearing. . . .

You can’t imagine.

After a while you’d think you’d get immune to being swore at.

You’d think you would get immune to being told that you were,

That you weren’t going to get home that night,

That you were going to get killed.

You’d think you’d get immune to being spit on.

You’d think you’d get immune to being . . . hit with rocks for a right

That was granted by the Supreme Court of this land, their law.What the hell am I doing out here for ten fish?

(excerpt from the public speech of Nick Hockings. From Larry Nesper, The Walleye War: The Struggle for Ojibwe Spearfishing and Treaty Rights, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002, pp. 158-62)

Why do you think he was willing to risk his life for ten fish?

Here is the perspective of a non-Indian

Letters to Editor. “Furious About Hunting, Fishing Ruling.” In Lakeland Times 2/3/1983.

Dear Governor: I am writing to voice my concern over the recent ruling on an 1854 treaty agreement with the Chippewa Indians. This antiquated law provides them the right to ignore hunting and fishing regulations adopted by the state of Wisconsin. I for one am furious about this miscarriage of justice and want you to be aware of my feelings. To begin with, both you and I were born on this soil and should be entitled to no more or less than the current generations living on reservations. I also feel that if this agreement is to be honored, it must further be stated that the pursuit of game must be conducted using the means at hand at the time of the agreement. In 1854 the cartridge as we know it today was not in existence. This one piece brass case with primer and slug didn’t show up until 1850. Also, vehicles with internal combustion engines must not be used to transport hunter or game to and from the hunting ground. Further, all boats, canoes, bows and arrows must be handmade by the participants. Freezers, refrigerators and any other modern day appliances cannot be used to store any game harvested under the terms of that treaty. I do not feel these provisions are any more ridiculous than this treaty being considered valid in today’s society. Heritage, it’s true, should be preserved for future generations and that is why we celebrate Octoberfest, St. Patrick’s Day and the like, but to include this ancient agreement as part of one’s heritage is stupid, to say the least. I intend to do all in my power to revoke this ruling and I implore you to do the same.

Do you think he views cultural heritage differently than Nick Hockings? Why do you think he argues that Ojibwa should have to hunt and fish without modern tools?

While sporadic violence occurred against Indians attempting to fish, responsible parties representing the tribes and the states began to negotiate. In 1990 Judge Crabb ruled that the tribal allocation of treaty resources is a maximum of 50 percent of the resource available for harvest. In 1991 she issued an injunction barring protesters from being near the shores during spearing in northern Wisconsin. Today Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan Ojibwa bands negotiate annual fishing limits for Indian spear fishing and angling.

Why did the issue of regulation generate such conflict?

Non-Indian Fears

Excerpts from “Ruling Allows Chippewa Indians Off-Reservation Hunting Anytime.” By Will Maines. In Lakeland Times, 2/3/1983, pp. 2, 5.

Wholesale slaughter of fish and wild game or a reasonable exercise of treaty rights? Open conflict or meaningful negotiations between Indians, white sportsmen and the Department of Natural Resources? People all over northern Wisconsin are asking those questions and more in the aftermath of a federal court decision last week which affirmed the rights of Chippewa Indians to hunt freely on all lands ceded by treaties of 1837 and 1842. The 2-1 majority decision by three judges sitting in the U. S. Seventh Court of Appeals in Chicago overturned a 1979 decision by Federal Judge James Doyle which said the Indians gave up those rights in a treaty negotiated in 1854. The decisions were based on an action entitled Lac Courte Oreilles Tribe versus Voigt (Lester Voigt, former head of the DNR). The majority decision, while paving the way for Chippewas to hunt and fish in any manner they choose on publicly owned lands, did grant Judge Doyle the right to determine if any restrictions should be placed on those rights if deemed necessary to protect the natural resources. The DNR has begun an appeal of the decision and is seeking an injunction against the Chippewa Indians to prevent them from exercising the treaty rights in question until all appeals are completed. If street talk is any indication, emotions are running at a high level in western Oneida and Vilas counties among white residents who fear a wholesale taking of game, primarily deer at this time. Those directly involved in tourist-related businesses are fearful tourism will be devastated if the ruling is not overturned before spring spawning runs of walleye, muskies and other gamefish begin and Indians harvest thousands of vulnerable fish. Hunters are claiming the local deer herd will be wiped out if tribal members are allowed to continue indiscriminate hunting of deer. Indian leaders are asking for restraint, and one member of the Lac du Flambeau RNR Committee said, “There have been a few deer killed since the decision, but I wouldn’t say a lot. The white community is going to have to recognize our rights in terms of the decision and the DNR is going to have to negotiate with us that understanding. We want to protect the natural resource as much as anyone, and we aren’t going to abuse the resource.” Two points brought up by tribal members at a Lac du Flambeau council meeting were that the tribe should begin looking into asking for redemption of all fine monies paid by members over the years for game law violations on ceded lands and a monetary settlement from the state for all the years it has not recognized treaty rights and prevented Indians from exercising them.

Subsequently, the tribes have been able to actively promote the improvement of fisheries and support environmental preservation generally, and they have cooperated with the states in a number of environmental projects.

How are tribes working to protect the environment?

Studying Fish Populations

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources cooperates with tribes to survey and monitor fisheries. Here a DNR staff member traps, measures, marks, and releases fish. Each spring, these DNR crews study and evaluate the fish populations in Wisconsin waters so that sound policies can be developed. Photo courtesy of Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources.

Reseeding Wild Rice on Little Traverse Bay Reservation

Ojibwa tribes and the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (an organization of 11 Ojibwa communities that hires biologists to work with other scientists to protect natural resources) work to restore and enhance wild rice in the ceded territories by reseeding rice beds in the fall. Tribal rice chiefs also work with the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources to set dates for the opening of off-reservation wild ricing. Enhancing rice beds also helps to attract waterfowl. Photo courtesy of Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC).

Monitoring the Loon, 2005

On Lac du Flambeau Reservation, the waterfowl populations are monitored. Students from youth programs help in this effort. Photo courtesy of Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC).

Walleye Hatchery, 2006

Tom Houle tends walleye eggs at the Bad River Hatchery. Many tribes operate hatcheries and stock fish in inland lakes as well as Lake Superior. Eggs are taken from speared fish. The eggs are fertilized, hatched, then the fish are reared and taken back to the lakes from which the eggs were taken. Photo courtesy of Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC).

Red Cliff Hatchery

Greg Fischer displays coaster brook trout, a native species, in one of the hatchery's indoor raceways. Hatcheries produce and stock coaster brook trout. Photo courtesy of Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC).

Lake Trout Monitoring, 2006

The GLIFWC performs annual lake trout assessments in Lake Superior to record size, growth, mortality, and abundance. Several thousand fish are measured each year by biologists. This data is used to determine the allowable catch, a figure that provides the basis for tribal and non-Indian lake trout harvest quotas in waters of the 1842 ceded area. Photo courtesy of Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC).

Whitefish Assessment

GLIFWC staff seine for juvenile whitefish in order to assess the population. The GLIFWC tracks trends in the numbers of fish by stock and determines how particular stocks are affected by fishing. They then make policy recommendations. Photo courtesy of Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC).

Rearing Sturgeon

Since 2002 surveys have been conducted in Manistee River, Michigan, to monitor the sturgeon population. It was discovered that the population was not sizable enough, so the tribe began the first portable streamside rearing facility to rear young fish to a size where they are likely to survive. This project was the result of consultations with elders, who did not want the sturgeon population removed to a hatchery, which is the usual means of rearing fish. The tribe's inland fisheries program is designed to preserve and enhance the tribal fishery while providing subsistence fishing opportunities to members. The program gives special focus to culturally significant fish (associated with clans) and those historically harvested in order to maintain healthy, abundant populations. Photo courtesy of Natural Resources Department, Little River Band of Ottawa Indians.

Monitoring the Bear Population

The Natural Resources Department includes in its mission the preservation and enhancement of wildlife resources that members harvest within the 1836 ceded territory. Special attention is given to culturally significant species and those animals that tribal members have historically relied upon. The bear rarely is hunted, but it is a clan symbol with great cultural importance, as the bear spirit helps humans in important ways. Tribal employees gather data on the bear population and habitat to monitor and manage the population so that it is healthy and sustainable. Photo courtesy of Natural Resources Department, Little River Band of Ottawa Indians.

Monitoring the bobcat population

The bobcat population and its habitat are being researched in order to develop scientifically-based harvest regulations. In addition to its wildlife projects, the Natural Resources Department monitors air and water quality and restores and monitors watersheds. In addition, they maintain a raptor repository to provide feathers for ceremonial purposes. Photo courtesy of Natural Resources Department, Little River Band of Ottawa Indians.

Tribal and state fisheries’ biologists use survey data to determine how many fish can be taken by tribes and sports fishermen without endangering fish populations. They set allowable catches for each lake. Tribes declare how many fish and which waters they will harvest, then the harvest is monitored and daily bag limits for sport anglers are announced. Tribes have developed their own hunting and fishing regulations on and off reservations and enforced them as tribal members take fish to feed their families, sell, and use in ceremonies. Through tribal and state cooperative effort, a system has been created that supports both tribal fishing rights and sports fishery, and tribes press the federal government for more stringent air and water quality standards that help maintain healthy fish for consumption by Indian and non-Indian populations alike.

Listen to George Meyer from the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC) Discuss the Effect of Court Rulings on Wildlife and the Environment

GLIFWC. Video courtesy of Indian Country TV, 2009. View transcriptFish rehabilitation projects are not merely about protecting fisheries. They play an important role in cultural revitalization. A good example is the case of sturgeon on the Menominee reservation.

Learn more about the Menominee Sturgeon Ceremony

Menominee Sturgeon Ceremony

When the Menominee settled at the present reservation, they settled at the Falls of the Wolf River, near what is now Keshena, even before the signing of the 1854 Treaty. This was such an important fishing place that the Menominee called it “NAMO’OUSKIWAMUT” or “sturgeon spawning place.” Up to the time that the whites placed dams on the Wolf River, Keshena Falls, on the present reserve was a great resort of these fish in the spring. Here the high water that follows the thaw and rain beats against a mass of rock making a drumming noise. Menominee folklore declares that this is the music of a mystic drum belonging to the Manitou who owns the cataract. They said that when this drum beats, the toads and the frogs begin the watering songs, and this sound calls the sturgeon to the pools and eddies below the cataract. There they formerly spawned and were then speared in large numbers. The Menominee Nation celebrate the return of the sturgeon with a feast and ceremonies . . . . The Department of Natural Resources had agreed to provide the Menominee Nation with ten lake sturgeon for the ceremony and spiritual events. This will be the fourth year that the Menominee Nation has celebrated the return of the sturgeon to their rightful home on the Menominee Indian Reservation. . . . The sturgeon has such historical importance to the Menominee that leaders chose the land for the present reservation partly because of the annual sturgeon migration up the Wolf River. There are now four dams that have been erected which stop the sturgeon at Shawano. The Wisconsin DNR had agreed to supply ten sturgeon which are then placed below Keshena Falls and allowed to swim in the Menominee waters. Prayer, song and offerings are part of the ceremony as this revered totem returns. Tribal members are allowed time to view the pre-historic looking fish before they are prepared. The sturgeon ceremony is only one of several that honor a clan symbol. Sturgeon are speared on Lake Winnebago, with last year recording a record harvest by sport anglers. In Potawatomi Traveling Times, May 11, 1996. The Newberry Library, McNickle Center Tribal Newspaper Collection.

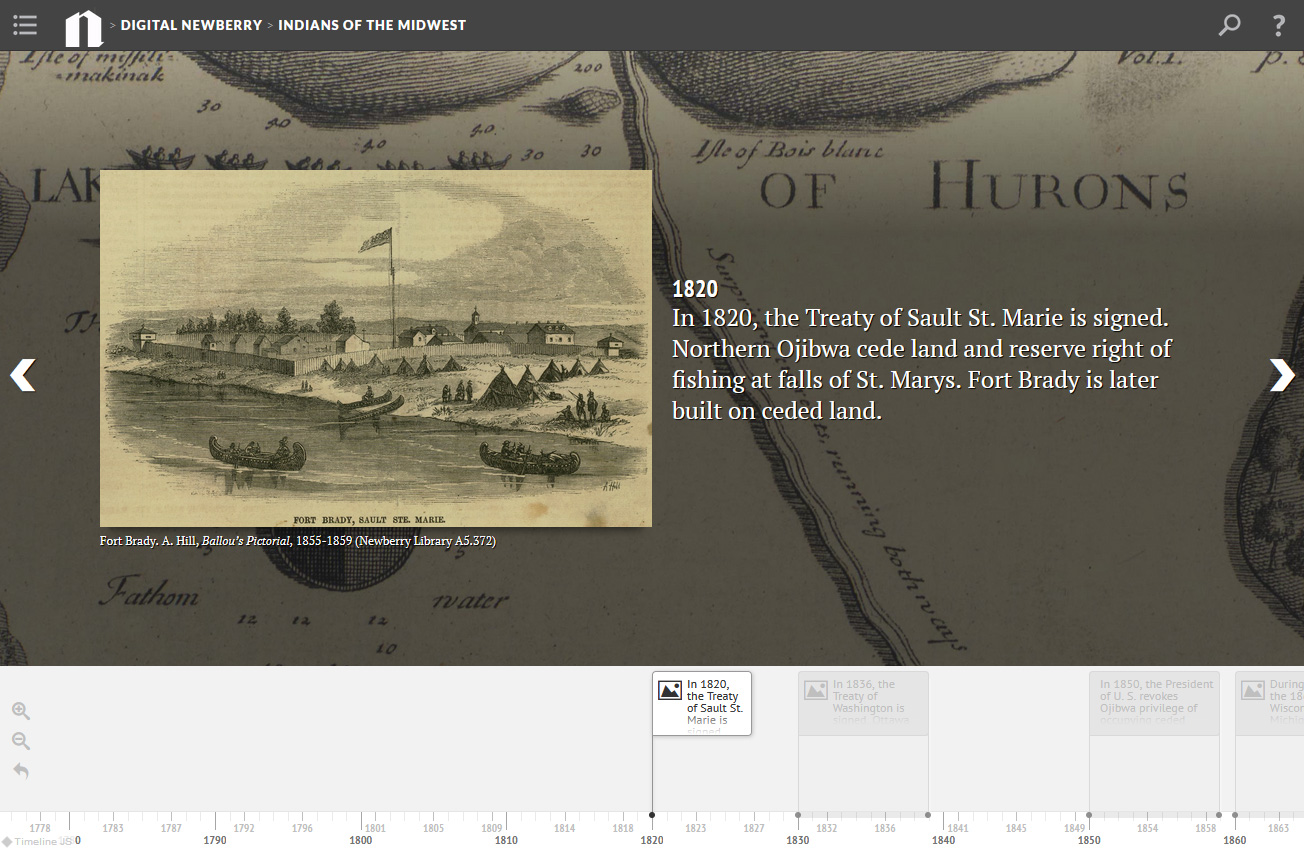

Interactive timeline: Explore the history of treaty rights

Albert (Abe) LeBlanc

In 1971, LeBlanc was arrested for fishing with a gill net and for fishing without a state license. Standing on treaty rights, his community filed a lawsuit against the state in Michigan state court. Photo courtesy of Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC).

Prayer Ceremony

In December 1998 Tobasonakwut, an Ojibwa spiritual leader from Canada, provided a pipe prayer ceremony outside the United States Supreme Court in Washington D.C. prior to an important hearing about the 1837 Treaty rights. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Mille Lacs and other Ojibwas on March 24, 1999. Even though the Ojibwa had won treaty rights cases, Minnesota refused to recognize these decisions, so the Mille Lacs Ojibwa took the case to the Supreme Court. Photo courtesy of Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC).

Sturgeon Ceremony, Menominee Reservation

This photo was taken at the annual sturgeon feast, a traditional thanksgiving ceremony for the return of the sturgeon. Because a dam blocks the sturgeon run today, the tribe and the Department of Natural Resources of the state of Wisconsin cooperate to transport sturgeon over the dam into Wolf River at the site of the tribe’s museum. There is a feast and men participate in the Fish Dance, followed by a powwow for the entire community and guests. Photo by Dale Kakkak, courtesy of College of Menominee Nation.

Sturgeon Ceremony, Menominee Reservation

The celebration also honors tribal elders and encourages cultural renaissance. Photo by Dale Kakkak, courtesy of College of Menominee Nation.

Test what you've learned about treaty rights