Menominee Sailor in World War II, 1943

1 2021-04-19T17:20:05+00:00 Newberry DIS 09980eb76a145ec4f3814f3b9fb45f381b3d1f02 8 1 Menominee Sailor in World War II, 1943. Photo courtesy of National Archives plain 2021-04-19T17:20:05+00:00 Newberry DIS 09980eb76a145ec4f3814f3b9fb45f381b3d1f02This page is referenced by:

-

1

2021-04-19T17:19:59+00:00

Sovereignty

1

image_header

2021-04-19T17:19:59+00:00

Above: Booth at a Dance. Photo by Orlando Cabanban (Newberry Library, Ayer Modern MS Seeing Indian, box 2, no. 46). View catalog record

By the 1930s, reform groups were criticizing Indian affairs policy by pointing to fiscal mismanagement and social injustice. In 1924, Congress had declared Indians to be citizens of the United States, yet they still were considered wards of the federal government and denied the right to vote in many states. The reform movement laid the groundwork for a major change in Indian policy when Franklin Roosevelt was elected president in 1933. His administration worked with Congress to pass legislation to allow Indians to participate in the recovery programs that benefited all Americans during the Depression.

In 1934 the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) ended the allotment of reservation land, permanently established trust title to Indian land, provided for the purchase of more land for Indians, established a credit program for Indian communities, and recognized the legitimacy of tribal governments. The new policy reaffirmed that Indians were tribal citizens, as well as U.S. citizens (just as other Americans had dual citizenship in other countries). Congress also provided for freedom of religion for Indian people.

Why was the IRA accepted by tribes and what provisions were in tribal constitutions?

Delegates from Minnesota Chippewa Tribe Meet with Federal Officials, January, 1940

Organized as a tribe consisting of six politically independent reservations, the Minnesota Chippewa sent their attorney with these delegates, the Tribal Executive Committee, to discuss matters that concerned all the reservations. They met with Assistant Commissioner of Indian Affairs, John Herrick. Before they organized under the Indian Reorganization Act, they had great difficulty arranging delegations and hiring attorneys. Left to right: John Hougen (attorney), Charles Roy (Bois Forte), Frank Broken (Leech Lake), Shirley McKenzie (credit agent, Bureau of Indian Affairs), Thomas Artell (White Earth), Sam Zimmerman (Grand Portage), M. L. Burns (Superintendent of Chippewa Agency), William Nickabaine (Mille Lacs). Photo courtesy of National Archives.

Works Progress Administration Project on Red Lake Indian Reservation, Minnesota, 1940

This Ojibwa crew was building a community center at Ponemah. These kinds of projects were launched nation-wide to relieve the economic distress caused by the Depression. Work was done on reservations as well as in other kinds of communities. Projects included forestry, road building, conservation, and construction of public buildings. The W.P.A. often used tribal leaders in these projects. Photo by Gordon Sommers, courtesy of National Archives.

Constitution and By-Laws of Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians, Wisconsin, 1936

The Indian communities in the Midwest already had governments in place at the time most accepted the constitutional governments established by the IRA, but the federal government largely ignored these leaders. The communities' acceptance of the new form of government reflected their hope that they would achieve home rule and greater influence over federal policy. The constitutional powers, although limited by a requirement that the secretary of the interior review many of the community leaders' decisions, included the right to obtain attorneys to pursue tribal interests, more control over their land and resources, and the right to determine their membership. The preambles of these IRA constitutions show the influence of federal officials, but also local understandings and concerns. The preamble of the Red Cliff Band's constitution emphasizes that the community is reestablishing their "tribal organization" and affirms the right of home rule and their treaty right to their land. One can read "tribal" to mean nationhood. Note that membership in the tribe depended largely on residency, rather than "degree" of Indian ancestry. The governing body was an elected nine-member tribal council, whose actions were subject to referendum by the community. The members of this council probably represented all the families in the community. (Newberry Library, Ayer 5 .U583 R31 1936).

Constitution and By-Laws of the Forest County Potawatomi Community, Wisconsin, 1937

The Forest County Potawatomi also intended to reestablish their tribal organization. Although the Potawatomi did not have a reservation set aside by treaty, their lands had been purchased and held in trust for them by the United States, and they expressed a commitment to conserving and developing their resources. In determining membership, they required that children of two members not residing on tribal land be of at least one-fourth Indian descent. If only one parent was a member who resided on the reserved land, the one-fourth blood requirement applied, as well. The governing body was the General Tribal Council, that is, all adult members. The Forest County Potawatomi adult members numbered not more than 120. (Newberry Library, Ayer 5 .U583 F71 1937).

Constitution and By-Laws of the Bay Mills Indian Community, Michigan, 1936

The Bay Mills Indian Community emphasized the protection of their property and resources. Membership in 1936 depended on residency and allowed for the enrollment of members of the Sault Ste. Marie Band living nearby but off the reservation. The residency requirement gave support to their commitment to a close-knit community. The constitution established that the governing body was the General Tribal Council, that is, all the adult members. The adult membership was less than 200. (Newberry Library, Ayer 5 .U583 B35 1936).

Constitution and By-Laws of the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community, Michigan, 1936

In this community, there were three small politically independent groups who organized "as a tribe." United, they had as many as 750 adult members. The federal government's recognition of their tribal status gave them more control over their affairs. The governing body was a twelve-member elected council representing the three groups. (Newberry Library, Ayer 5 .U583 K26 1937).

Constitution and By-Laws of the Lower Sioux Indian Community in Minnesota, 1936

In their constitution, the Lower Sioux promised to support the constitution of the United States and that of Minnesota, which may have been an attempt to address the lasting animosity from the “Sioux Conflict.” Membership was offered to resident Dakotas enrolled on other Sioux reservations upon their transfer to the Lower Sioux community. In what was perhaps another effort to reassure the federal government, members who received land assignments from the Community Council were required to cultivate it. The Lower Sioux also affirmed their treaty rights to hunt and fish. The governing body was a five-member Community Council whose actions were subject to a referendum by the eligible voters. These referendums supported the ideal of consensus decision-making. In later years, all these reservation communities revised their constitutions. (Newberry Library, Ayer 5 .U583 L917 1936).

Minnesota Chippewa Tribal Headquarters, Cass Lake

Today this overarching tribal organization provides services and technical assistance to six Ojibwa reservations in Minnesota. Since its organization in 1934, it has expanded. For example, it administers educational projects for urban tribal members. The members of the six Ojibwa bands also are members of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe. Photo courtesy of Minnesota Chippewa Tribe.

Indian people subsequently pressed for more control over their communities and more personal freedom. Indian veterans of World War II introduced more assertive strategies in their communities and played an important role in the establishment of the National Congress of American Indians in 1944. This organization lobbied in Washington DC for Indian rights.

Do you want to learn more about veterans?

Menominee Sailor in World War II, 1943

Dan Waupoose poses for U.S. Navy photographer while wearing a feathered headdress. In September 1940 the Congress enacted the draft and declared war in December 1941. 42,000 Indians were eligible for the draft. The B.I.A. unsuccessfully tried for an All-Indian Division of Indian soldiers. Indians were assumed to be good fighters and integrated into White units. During World War II 25,000 Indian men served and several hundred Indian women joined the service as WACS and WAVES. In the Army Signal Corps, Oneida, Ojibwa, and other soldiers used their native language in code work. Indian soldiers were recognized for their distinguished service in the Army, Navy, Marines, and Army Air Corps. Veterans later became important participants in tribal government and in political activism generally. Photo courtesy of National Archives.

Visiting Veterans Memorial, Leech Lake Reservation, 2008

These students from the tribal college are visiting the memorial as part of learning about the history of their community. They will write about their experience. Photo by Mark Lewer, courtesy of Leech Lake Tribal College.

Honor Guard, Lac Vieux Desert Powwow at Watersweet, Michigan, 2008

These veterans carry staffs signifying their military experience. They lead the dancers into the arena at the start of the powwow. In doing this, they are honored for their service and, at the same time, they honor all the veterans. Photo courtesy of Lac Vieux Desert Band.

Exhibit Honoring Veterans

This is part of a National Museum of the American Indian traveling exhibit, "Native Words, Native Warriors," which honors American Indian Code Talkers from more than twelve tribes, who served in World War I and II. Photo courtesy of Match-e-be-nash-she-wish Band of Pottawatomi.

By the 1950s, responding to a backlash among their constituents, Congress tried to reverse the policy of supporting tribal communities. New legislation provided for the termination of the trust relationship if Congress decided that a tribe no longer needed protection. In such cases, funds could be withdrawn for tribal health and education. And the trust title to land protected Indians from the loss of land to state and local taxes. In 1954, Congress terminated the Menominee, who had a lumber business that was competitive with non-Indian lumber interests.

Congress also passed legislation enabling Michigan and Wisconsin to extend legal jurisdiction over Indian reservations without tribal consent. Many Indian children were removed from their communities and sent to non-Indian foster homes. And, a national “relocation” program promoted the resettlement of reservation Indians in cities, including Chicago, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, and Grand Rapids.

What has community life been like for urban Indians since relocation?

Social Dance at American Indian Center Powwow, 1968

Indian centers began to appear in cities after the start of the relocation program. A major activity in the early days of the center in Chicago was the powwow. It was a multi-tribal celebration of various styles of dancing and songs. The dance shown here was a couple dance, popular with young people. Photo by Orlando Cabanban (Newberry Library, Ayer Modern MS Seeing Indian, box 2, no. 11).

American Indian Center Powwow, 1968

The powwow, which brought together singers from many tribes, helped diffuse different styles and contributed to creativity. These singers sit around the large drum, which they beat in unison. Facing the camera are Sam Sign and Archie Blackowl. The first annual American Indian Center powwow began in 1954. In the 1960s, monthly powwows drew up to 500 people. Photo by Orlando Cabanban (Newberry Library, Ayer Modern MS Seeing Indian, box 2, no. 19).

1958 American Indian Center Dance Club, Chicago

The club traveled widely, encouraging powwow activity, especially in urban centers. Top row, l to r: Harry Funmaker, Linda Benson, Ernest Naquayouma Sr., Ruby Keahna Funmaker, Ernest Naquayouma Jr., Norma Bearskin Stealer, Ben Bearskin Sr., Barbara Keahna, James Passafume. Middle row, l to r: Dennis Keahna, Pauline Logan Funmaker, Ramona Naquayouma, Stella Johnson, Lillian Naquayouma, Kenneth Funmaker. Bottom row, l to r: Bernadette Miner, Avery Lonetree, Laura Miner, Danny Miner. Photo by Dan Battise (Newberry Library, Ayer Modern MS Seeing Indian, box 1).

Booth at a Dance

At the Indian Center in Chicago, artists sold their work and people sold food, usually to raise money for the center. Photo by Orlando Cabanban (Newberry Library, Ayer Modern MS Seeing Indian, box 2, no. 46).

Basketball Players at the American Indian Center in Chicago

The center encouraged children to come there for educational services, participation in clubs, and opportunities to play sports. Photo by Orlando Cabanban (Newberry Library, Ayer Modern MS Seeing Indian, box 2, no. 31).

1960-61 Boys' Basketball Team, with Cheerleaders, American Indian Center at Chicago

The team had a fan base among Indians in Chicago. They played against teams on reservations and other urban areas. Photo by Dan Battise (Newberry Library, Ayer Modern MS Seeing Indian, box 1, no. 8).

Girls' Basketball Team

The girls' team also was popular. Photo by Dan Battise (Newberry Library, Ayer Modern MS Seeing Indian, box 1, no. 31).

Canoe Race

The Canoe Club at the American Indian Center in Chicago was active in the Chicago area, paddling on the Great Lakes in the company of crews from the reservations, and the members traveled to other regions to participate in races. Shown are Art Elton, Tony Barker, Archie Blackelk, and Paul Goodiron. Photo by Orlando Cabanban (Newberry Library, Ayer Modern MS Seeing Indian , box 2, no. 17).

Day Camp Outing

These children are attending a summer camp sponsored by the American Indian Center in Chicago. Photo by Orlando Cabanban (Newberry Library, Ayer Modern MS Seeing Indian , box 2, no. 18).

Family's House in Chicago

For families like this one, the American Indian Center in Chicago provided a place to make social ties, reaffirm traditional Indian identity, develop leadership potential, and obtain social services. Although the center's activities were multitribal, tribal clubs (like the Winnebago Club and the Council of Three Fires) were organized. The first center opened in a rental space downtown in 1953. In 1963, the center relocated to uptown Chicago, where most of the Indians lived, and in 1966, the center moved to its current location at 1660 W. Wilson Avenue. Leaders at the center offered criticism of termination policy and the faulty implementation of the relocation program. The center was funded by private donations. Photo by Dan Battise (Newberry Library, Ayer Modern MS Seeing Indian, box 1).

American Indian Center, Chicago, 2009

The center opened at the instigation of the Chicago Indian community with assistance from the American Friends Service Committee and other philanthropic organizations. It was the first urban center in the country. At this time, Chicago was one of five original relocation cities. Illinois was without a large in-state reservation, so the center drew Indians mostly from outside the state. Today the center serves people from 50 tribes. The 2010 census counted almost 11,000 Native people in Chicago. The American Indian Center has academic, health, and social service programs. It is a major gathering place for Indians in Chicago, where many activities take place-powwows, bingo, potlucks, family and community celebrations, and wakes. The Trickster Gallery is the only Native operated arts institute in Illinois. It offers gallery space, tours, and workshops. The center operates with a board of directors, elected by the Chicago Indian community. Photo courtesy of Flickr Creative Commons, user Zol87.

Minneapolis American Indian Center

The wood collage is by Grand Portage Ojibwa artist George Morrison. The center was founded in 1975. It offers employment training, senior citizens assistance, youth programs, and health and wellness services. The center operates an art gallery and otherwise supports Indian cultural traditions. The 2010 census counts almost 9,000 Native people in Minneapolis-St.Paul. Photo courtesy of Randy Croce.

Federal policy changed again in the 1960s, when Democratic administrations extended War on Poverty programs to Indian communities, revitalizing tribal governments in the process. The American Indian Civil Rights Act was passed in 1968, which, among other things, required states to obtain Indian consent before assuming jurisdiction on Indian land. Many communities started or elaborated on “powwows,” rituals that served as expressions of Native pride.

View powwow dancing

Powwow. From Since 1634: In the Wake of Nicolet. Video courtesy of Ootek Productions, 1993. View transcriptIn 1968, the American Indian Movement (AIM), a new organization whose membership was young and often from urban areas, began to use public demonstrations to publicize the social injustices that Indians still faced.

Do you want to learn more about AIM?

Dennis Banks, New York, 1967

Banks, one of AIM's original members, joins other demonstrators against the war in Vietnam. Banks grew up on Leech Lake Reservation, and after years in Indian boarding schools, service in the Air Force, and a stint in prison, he obtained employment in the Honeywell Corporation in Minneapolis. He and Clyde Bellecourt founded AIM in 1968 to advocate for Indians in the Minneapolis area. They organized to monitor arrests of Indians in an effort to stem police brutality. AIM expanded its activities and achieved national prominence, eventually organizing a march on Washington to protest the United States's treatment of Indians. Photo by Dave Tyson.

American Indian Movement Demonstration, ca. 1978-83

Clyde Bellecourt (White Earth Ojibwa) is speaking to a rally to stop the potential closing of Little Earth of United Tribes, a primarily American Indian housing development in Minneapolis. Bellecourt was one of the original founders of AIM in Minneapolis. He attended Indian boarding schools, served time in prison, and then obtained employment in Minneapolis. Most of the initial members of AIM were Ojibwa, from urban and reservation areas. Photo courtesy of Randy Croce.

Political Rally, 1982, with AIM Participation

This was a march by several progressive groups in Loring Park, Minneapolis. Clyde Bellecourt holds the microphone. Below him on the far left is Bill Means and in the lower right, Floyd Westerman. AIM made alliances with churches, progressive attorneys, and liberal groups, especially around the issue of the nuclear power plant next to the Dakota Prairie Island Indian Community on the Mississippi River. Photo by Randy Croce.

AIM at International Indian Treaty Conference

The theme of the conference was unity among Native people all over the world. The conference was held on the White Earth Reservation in 1981. Vernon Bellecourt is seated on the left. Photo courtesy of Randy Croce.

Listen to Dennis Banks discuss the formation of AIM

AIM. Video courtesy of WDSE-Duluth/Superior, MN, 2002. View transcriptIn the 1970s, Indian advocacy and public pressure led to a new emphasis on Indian sovereignty. Both Congress and the Supreme Court acknowledged that the federal government was bound by its treaties with Indian tribes and that tribes had the right of self-government and economic self-sufficiency. In 1973, Congress restored the Menominees’ tribal status and put their land back in trust.

Listen to Menominees explain how they regained their status as a federally recognized tribe.

Menominee Restoration. From Since 1634: In the Wake of Nicolet. Video courtesy of Ootek Productions, 1993. View transcriptWith support from President Richard Nixon’s administration, in 1975, Congress provided that tribal governments, not the federal government, would administer federal services and programs. Tribes took over responsibility for child welfare, ending the adoption of Indian children by non-Indians. Tribal programs employed Indians and tried to provide more culturally appropriate services.

What kinds of services do tribal governments provide?

Head Start Program, Leech Lake Reservation

On this occasion the tribe's Gaming Department donated toy log cabins to the children in the program. Profits from tribal businesses help support the Head Start program, which also receives funds from the tribe's contracting relationship with the federal government. The Head Start program stresses culturally relevant activities. At Leech Lake, the tribe owns three casinos and two hotel-resorts. Income is used to support many community projects and programs. The logos of the casinos reflect the Ojibwa heritage, particularly close relations with the natural world. Photo courtesy of Gaming Department, Leech Lake Reservation.

Language Class at the Waadookadaading School in the Lac Courte Oreilles community

Brian McInnes teaches the Ojibwa language at a language immersion school, where children spend the day hearing only the Ojibwa language. The Ojibwa community supports encouraging the Native language because it is intimately connected to indigenous knowledge about the world. Photo courtesy of Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC).

Clinic, Menominee Reservation

The clinic, which was the first Indian-owned and operated clinic in the United States, opened in 1977, and since then it has been expanded several times. The tribe gives significant financial support to the clinic and the health programs it undertakes. Indians without health insurance are treated without charge. The clinic provides medical, dental, and optical services and operates a pharmacy. Photo courtesy of College of Menominee Nation.

Forestry Work, Fond du Lac Reservation

Here, a tribal employee is managing a prescribed burn. When conditions are right, the forestry program does this to reduce the amount of fuel that would otherwise support fires, to open up areas to wildlife, or to renew habitats for plants like blueberries and trees like the white pine. The tribe's forestry program includes fire prevention education, maintains the health of the forested reservation land, and suppresses wild fires within or near the reservation, as well as assists on other fires in the region. Photo courtesy of Forestry Department, Fond du Lac Tribe.

Health Department Wellness Program at work, Match-e-be-nash-she-wish Band

In 1954, Congress created the Indian Health Service (IHS). Before this, agencies might have a doctor assigned to cope with all health issues. The Department of Health and Human Services oversees the Public Health Service for all Americans. The IHS is a subagency charged with providing medical and hospital care for Indians who are members of federally recognized tribes. The IHS is seriously underfunded despite the fact that the mortality rate is higher and life expectancy lower for Indians than the U.S. average. Diabetes and tuberculosis mortality is also significantly higher, as is the suicide rate. Tribes contract with HHS to provide health care and preventive services like the Match-e-be-nash-she-wish Wellness Program, in an effort to improve health conditions. Photo courtesy of Match-e-be-nash-she-wish Band of Pottawatomi.

Bois Forte Community Center

This center has meeting rooms, fitness equipment, and space for activities. The Tribe began obtaining loans and grants from the U. S. Department of Agriculture Rural Development Program in the 1990s. This program works to improve sanitation (water and sewer services), infrastructure, and public facilities, and it was responsible for this center. Photo courtesy of United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Sault Police Car

Tribal governments develop law and order codes and contract the operation of police departments from the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Tribal governments are responsible for overseeing the work of the police force. Photo courtesy of Daryl McGrath

In 1978, tribes not recognized by the federal government gained opportunities to have their tribal status legalized, and Congress increased funding for education.

What do tribal colleges do?

College of Menominee Nation Campus

The college began in 1993 in a small house, moved to a trailer, and over the years expanded to what it is today. It is one of 36 tribally controlled community colleges in the United States. Fully accredited, it offers academic and vocational programs and infuses the curriculum with Menominee language and culture studies. The college provides job placement service and its students can transfer credits to the University of Wisconsin. Tribal colleges, like this one, have relatively small student bodies, which benefits Native students by increasing graduation rates and success at four-year institutions. At tribal colleges, the Board of Directors, administration, and many faculty members are Indian. Photo courtesy of College of Menominee Nation.

Graduation, College of Menominee Nation

Some graduates continue their education and others enter the job market. The majority of students at tribal colleges are women, who have been able to improve their economic circumstances through education. Tribal colleges are major employers in Indian communities and they provide job training and consultation for economic development. Photo courtesy of College of Menominee Nation.

Drama Class, College of Menominee Nation

These students performed a dinner theatre production of a play. Many people from the community attended the performance, held at the tribe's casino complex. The play reflected on Menominee history. Photo courtesy of College of Menominee Nation.

Sculpting, Leech Lake Tribal College

Student Ketta Flores is following Ojibwa tradition by learning to sculpt. Leech Lake Tribal College offers a two-year liberal arts program. Accredited, it provides traditional academic subjects, Native studies, and vocational courses. The college also offers an honorary degree for elders as part of a life-long learning opportunity and an effort to support the role of elders in contemporary life. Tribal colleges, like this one, come out of what has been called "the tribal college movement," which developed Indian leadership, encouraged Indians to regain control of their children's education, improved access to higher education, and promoted cultural revitalization. The movement emphasized using Native cultural traditions as a framework for academic rigor and as a means to address poverty in Indian communities. Photo by Mark Lewer, Courtesy of Leech Lake Tribal College.

Making moccasins, Leech Lake Tribal College

Student Supaya Therriault makes moccasins as a classroom activity. This project, as well as sculpture projects, help to support the college's goal of including Anishinaabe language and culture in the curriculum. Photo by Mark Lewer, Courtesy of Leech Lake Tribal College.

Biology Class, Leech Lake Tribal College

Casondra Gagner works on an assignment. Photo by Mark Lewer, Courtesy of Leech Lake Tribal College.

Class on Plant Identification, Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwa Community College

Instructor Larry Baker points out and discusses plants during a class. The college was established in 1982. Accredited, it offers post-secondary and continuing education programs. Tribal colleges are underfunded and do not receive state funding as other community colleges do; yet, at least 25 percent of the students are non-Native. Most Indian community colleges admit non-Indians and provide them with educational opportunities they might not otherwise have. Photo by Shanna Clark, courtesy of Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwa Community College.

Class on Indigenous Foods, White Earth Tribal and Community College

Here members of the class are tapping maple trees to obtain sap that will be made into syrup and cakes. Photo courtesy of White Earth Tribal and Community College.

Tracking Animals, White Earth Tribal and Community College

Here, in the study of zoology, instructors use indigenous "ways of knowing" to complement other pedagogies. Classes held in the forest accomplish the same objective. This program reflects the goals of the tribal college movement. Photo courtesy of White Earth Tribal and Community College.

The Supreme Court affirmed tribes’ exemption from state taxes and exempted tribal citizens living on reservations from state property and sales taxes. In the 1980s and 1990s the Court also affirmed the Ojibwas’ treaty rights to hunt and fish on ceded lands and the right of tribes to operate gaming establishments on trust land without state regulation. In the wake of the support for tribal sovereignty and increased sensitivity to Indian issues, signs of a backlash began to emerge.

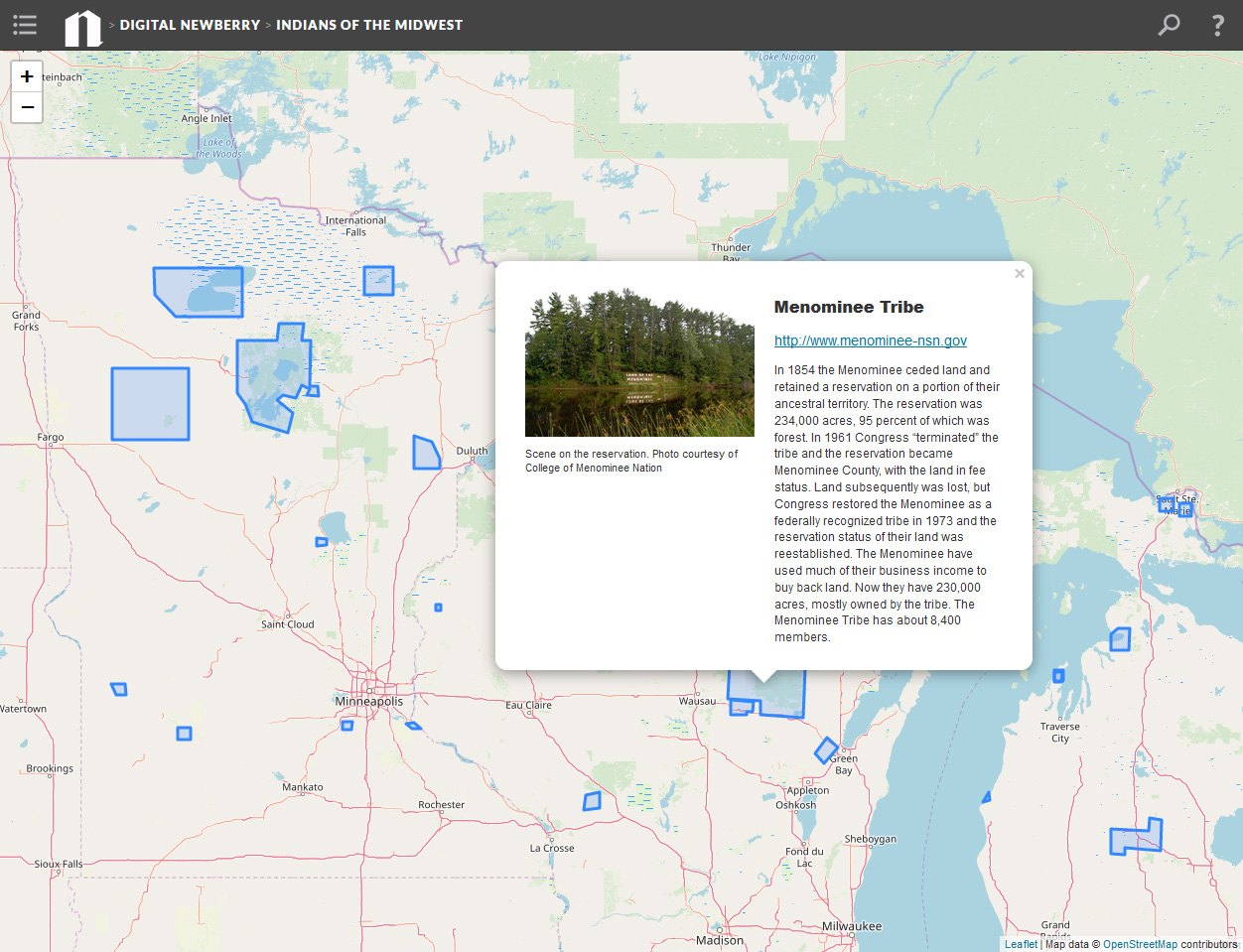

Interactive map: Explore federally recognized tribes

Ojibwa Home, 1935

This photo was taken at Grand Portage. Indian families struggled economically during the early 1930s. Photo courtesy of Minnesota Historical Society.

WWII Indian Worker

Kay Lamphear, Defense Plant Worker at Allis Chalmers Manufacturing Company in Wisconsin, 1942. This Indian woman operated a punch press, machining diaphragm blades for airplane engines. During World War II many Indian women and men worked in defense plants and the airplane industry as riveters, machinists, and inspectors. The tribes also purchased war bonds or donated money to the war effort. Photo by Ann Rosener, courtesy of Library of Congress.

Jingle Dress

About the time of World War I, when the Spanish influenza epidemic spread through reservation populations, an Ojibwa girl became ill. Her father sought a vision to save her life. He received a message from spirit beings that if she wore a particular dress and danced to particular songs, she would recover. She followed these instructions and regained her health. Subsequently, she founded the first Jingle Dress Society, which was associated with curing and with women curers. In Ojibwa belief, supernatural power moves through the air, for example, through sound, which is why singing is an act of prayer. The jingle dress has rows of metal cones that rattle when they move, conveying sound in rhythmic accompaniment to the songs. Originally, the cones were made from round snuff can lids. So this was a ceremonial dress and the dance was a prayer for healing. People gave gifts of tobacco to the dancer as a request for her to pray for the recovery of people who were ill. In the 1980s, as songs and dances were revived across Indian country and transferred from tribe to tribe, the Jingle Dress Dance became widespread and today is one of the contest dances in powwows like the one in Minneapolis (shown above). For Ojibwa, it remains associated with ceremonial healing. Photo courtesy of Little Earth of United Tribes, Minneapolis, MN.

Zoar Ceremonial Hall

This building and the adjacent lodge (note the frame at the side of the building) are used by the members of the Zoar community on the Menominee Reservation. Traditional ceremonies gained participants after the restoration of the Menominee reservation community. Photo by Dale Kakkak, courtesy of College of Menominee Nation.

Menominee Restoration

In 1954 the Menominee were self-supporting, even paying the salaries of federal government employees. They supported the Catholic hospital, schools, and their own utility company from the profits of their lumber business and a legal settlement they received. Congress pressed the Menominee to agree to termination, that is, relinquishment of the trust status of their land and property. Ignoring Menominee resistance, Congress put termination into effect in 1961. What followed was a major social and economic decline. Their capital was dissipated because the federal government forced them to pay the costs of termination. The tribe had to sell their utility company and close the hospital. With the loss of medical care, the community experienced a tuberculosis epidemic. Non-Indians took over the management of tribal resources, while tribal members became “stockholders” in Menominee Enterprises, which worked to sell Menominee land to non-Indians. By 1970, DRUMS, an advocacy group that worked to reverse termination, emerged, and led demonstrations, obtained legal counsel, and lobbied in Washington DC. Ada Deer (shown at right), a Menominee with experience in dealing with the federal government, directed the lobbying effort in Washington. In 1973 Congress was persuaded to pass the Menominee Restoration Act and President Nixon signed it. The Menominees reorganized their tribal government, got reservation land restored to trust status, rebuilt the lumber mill, built a health facility, and embraced the revitalization of traditional religion. Photo courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society.

Ojibwa Houses on Bad River Reservation, built by HUD during the 1960s

Compare these houses to the one above (Ojibwa Home, 1935). Since the 1960s Indian housing has improved significantly, after the federal government began to support housing programs on reservations and elsewhere. The Indian Health Service, Bureau of Indian Affairs, and Housing and Urban Development began work to improve sanitation (for example, installing indoor plumbing and monitoring water quality), repair homes, and construct homes for rent, purchase, or elderly occupation. After 1975, tribes could contract with the federal government to supervise home improvement and construction projects and they aggressively sought such contracts. Photo courtesy of Charlie Rasmussen, 2011.

Test what you've learned about Indian sovereignty

-

1

2021-04-19T17:20:01+00:00

Stereotypes

1

plain

2021-04-19T17:20:01+00:00

For centuries, Americans have regarded Native Americans as the “Other,” that is, fundamentally different from themselves. Majority Americans have viewed the Other (“Indians”) as lacking something, either in a good way or a bad way. Such a characterization of Indians is a stereotype. It does not represent the reality of Native American cultures and histories. It lumps together and defines Indians as somehow deficient. Stereotypes about Indians are represented in the imagery Americans have used to portray them and, in this imagery, there are two contradictory conceptions of Indians—favorable and unfavorable—that reflect the use to which the image is put.

Negative Portrayals

The most prevalent negative images of Midwest Indians in the 18th and 19th centuries showed them killing and/or capturing White people, especially women. Captivity images (often accompanying novels or “captivity narratives”) showed brutish Indian males overpowering terrified White women who, it was implied, would experience unspeakable horrors. This message was a one-sided one, that is, the brutality of war was ascribed to Indians alone. In reality, non-Indians killed many defenseless Indian women and children, took captives (whom they often killed), and tortured Indians; however, these scenes were not popular subjects for artists.

What messages do captivity images convey?

Notice of a Massacre, ca. 1832

This "notice" is copied from an advertisement for captivity narratives that purport to be about the abduction of two women from a frontier settlement, probably in the Ohio River country, during an Indian attack. The text, "Horrible and Unparalleled MASSACRE!" and "Women and Children Fall Victim to the Indian's Tomahawk," represents Native people as brutish aggressors. Actually, in the Ohio Valley, the settlers would have been trespassing and are as likely as not to have attacked Indians. In the illustration, the partially-clothed Indians appear dark and dangerous, while the White child is terrified and the woman helpless and vulnerable. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division (LC-USZ62-45716).

The Abduction of Daniel Boone's Daughter by the Indians, 1853

This famous oil painting by Charles F. Wimar is an allegory of the clash between "savagery" and "civilization," and it reflects the attitude of Americans toward Indians in the early 19th century. The Shawnee Indians are dark and frightening and have a hunted look. Behind them is the setting sun, which signals the Indians' way of life is ending. The woman, representing Jemima Boone, has a Madonna-like pose and looks pure and vulnerable. Shawnees and Cherokees kidnapped Jemima in 1784, in an attempt to prevent trespass into their territory. Shortly after the abduction, Daniel Boone rescued his daughter unharmed. Charles F. Wimar was an American who studied painting in Germany and used idealized figures in poses borrowed from European religious painting traditions. Painting by Charles F. Wimar, courtesy of Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Washington University in St. Louis, gift of John T. Davis, Jr., 1954.

Captivity during the Sioux Conflict, 1864

This is an illustration for Miss Coleson's Narrative of Her Captivity among the Sioux Indians. The description of the book's content is lurid: "Terrible sufferings," and "providential escape" by the "victim of the Indian outrages in Minnesota." This publicity echoes the press accounts at the time of the conflict, in which the Indians holding captives were accused of atrocities "unparalleled" in the history of Indian warfare, including the rape of female captives. The illustration actually refers not to Miss Coleson's experience but to that of a Native woman captured earlier by the Sioux. Ann Coleson's own account, publicity aside, mentions that her captor gave her food and suitable clothing for travel back to his village. In the village, she was well treated. She notes that her captor wanted her as a wife but that she refused him. He did not molest her or allow other men to do so. The Dakota women were kind to her and she learned that the village intended to ransom their captives. When the Dakotas moved camp, she escaped in the dark. In the many accounts by captives during the Sioux Conflict, they were treated kindly and protected by the Dakota. The abuse of women was exceedingly rare, even though Indian women had been frequently abused by settlers. Ann Coleson, Miss Coleson’s Narrative of Her Captivity Among the Sioux Indians (Newberry Library, Graff 803).

Native people were fighting for their homelands, farms, and rights to territory they needed in order to make a living for their families. Usually, these regions had been guaranteed them by the federal government in treaties, but many Americans violated the law and trespassed, often attacking Indians in the process, as happened in the Ohio Valley. When Indians tried to defend themselves, they were attacked by troops. According to United States policy, land cessions had to be agreed to by Indians. In 1812 Tecumseh’s resistance movement was about the refusal of a component of the Indian groups in the region to be coerced into leaving their homes, fields, and hunting territories. This also was the case with Black Hawk, whose followers fought to remain in their villages, which they had not agreed to leave. The Sioux Conflict was a rebellion against fraud committed by Americans who seized Dakota land and assets without regard for the promises made during treaty negotiations. The Indian point of view on these matters largely escaped serious consideration by the general public.

By the late 19th century, Indians had been largely removed from Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and southern Michigan. Some were on reservations in northern Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin, where they were entitled by treaty to economic assistance. Reservation Indians were portrayed in popular art as depraved—lazy, incompetent, and immoral. In reality, Native people worked for American businesses and settlers in various capacities for very low wages—which enabled Americans to settle the region. Indians worked hard to supplement low wages by hunting, fishing, and gardening at the same time that the states tried to restrict these pursuits. In Michigan, Indian farmers (who generally had lost the land guaranteed them by the United States) bought land and paid taxes on it. Many Indian communities formed around and supported schools and Christian churches. Indian poverty was fueled by the failure of the United States to fulfill treaty agreements and prevent the exploitation of Native communities. Federal investigations eventually documented theft of land, property, and resources such as timber. Indian leaders worked to prevent or get compensation for these abuses. Much Indian imagery ignored the realities of economic and political adjustment and portrayed Indians negatively.

Since the 1970s, Congress and the Supreme Court have supported tribal sovereignty, that is, the recognition of the tribes’ right to self-government and economic self-support through management of their own resources. In media representations, we see Indians portrayed as lazy, greedy, and “fake” (not “really” Indian) as they pursued these rights. Americans did not feel less American after they abandoned 19th century hair styles, horse and buggy transport, and gas lights. Yet, they viewed “real” Indians only as people from the past, who were not interested in making money and not capable of managing their own affairs. Indian communities’ efforts, for example to open casinos, or attain federal recognition or treaty rights to fish in certain places, have often been met with ridicule or hostility.

Romantic Portrayals

There also is a long history of Indian imagery that portrays Indians favorably. Portrayals of Noble Savages in the 18th and 19th centuries showed them as guileless or simple, strong, and helpful to Americans. Indians who signed cession and removal treaties appeared to be willing participants, in awe of White Americans. In fact, treaties often were signed under duress, only after Indians had argued futilely that they could stay on their land and still be useful participants in American society. Indians were farming successfully (even commercially) in many parts of the Midwest at the same time they were characterized by Americans as “hunters,” unable to make good use of the land they were asked to cede.

By the late 19th century, Indian portrayals stressed the inevitable extinction of “doomed” Indians. These images evoked pity for a vanishing people. But in the Midwest there were Indian communities that refused to leave their homeland. By the late 20th century, they had managed to retain or attain title to land and political recognition as tribes.

Most of the representations of Indian people in the Midwest showed Indians in long-ago settings, living simple, close-to-nature lives and, in their association with a past “Golden Age,” posing no threat to Americans in the early 20th century or beyond. In fact, this romantic image of Indians of yore was used to sell products and develop a regional economy in the Great Lakes region.

Look at a brochure from a Hiawatha pageant performed for tourists in Michigan in 1914

The Indian Play Hiawatha, 1914

The Grand Rapids and Indiana Railway Co. published this brochure for an annual pageant, held in Petoskey, Michigan. The railroad sponsored and advertised the performance to generate tourist business on the railway. At Petoskey, in northern Michigan, the company built a bathing beach, dining hall, and Indian craft shop that sold the work of Grace Chandler Horn. Horn's photos illustrate the pamphlet. Hiawatha was a fictional character created by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in his epic poem "The Song of Hiawatha." The poem became very popular, inspiring pageants like this one, as well as themes in American art. The Ojibwa actor on the cover is dressed as a 19th century Plains Indian (from west of the Mississippi River), carrying a bow and arrows. Photo by Grace Chandler Horn, courtesy of Grand Rapids Public Museum.

Young Hiawatha

The play follows the Henry Wadsworth Longfellow poem, "The Song of Hiawatha," and the pamphlet provides lines from the poem to accompany the photos: "From the red deer's flesh Nokomis made a banquet in his honor. Scarce a twig moved with his motion, scarce a leaf was stirred or rustled. All the village came and feasted, all the guests praised Hiawatha." In these scenes, Hiawatha is an Ojibwa child, being raised by his grandmother `Nokomis. He shows signs of his heroism and nobility even as a small child, as Longfellow tells the story. The background for the play is nature, the shore and forest. The village is represented by Plains tepees and Hiawatha wears a Plains headdress (which a child would not have worn). This scene contributed to the themes of Hiawatha as hero and Indians as part of nature and associated with the past. The actors in the pageant were wearing costumes and performing. In their everyday lives they dressed and lived in a manner very similar to non-Indians in the area. Photos by Grace Chandler Horn, courtesy of Grand Rapids Public Museum.

Laughing Water

"From the wigwam he departed. Leading with him Laughing Water. And she follows where he leads her, leaving all things for the stranger." This scene dramatizes Hiawatha's courtship of Laughing Water (Minnehaha), a Dakota woman. Hiawatha disregarded his grandmother's advice to marry an Ojibwa. Instead, he traveled west and won the beautiful Laughing Water and, in so doing, created a peace between the Ojibwa and Dakota. He returned with her in his canoe to his people. The actors are wearing Plains-style clothing but the canoe is Ojibwa. Most Americans at this time associated Indians with the Plains peoples who had been so much in the news and in wild west shows in the late 19th century. Photos by Grace Chandler Horn, courtesy of Grand Rapids Public Museum.

Wedding

"Sumptuous was the feast Nokomis made at Hiawatha's wedding." In this scene, Hiawatha and Minnehaha are married. The village scene involves children and men and women of different ages. The mortar and pestle are being used as Ojibwas used them to grind corn. But the tepee and clothing reference the Plains Indians. Photo by Grace Chandler Horn, courtesy of Grand Rapids Public Museum.

Falls of Minnehaha

"Hear the Falls of Minnehaha calling to me from a distance!" In this scene, Minnehaha is dying in the midst of a famine, and she hears the sound of the falls near her home in the west. The actress's headband is probably influenced by Hollywood portrayals of Indians wearing a headband with a feather. The dying Minnehaha suggests the inevitable dying-out of Indians generally. Photo by Grace Chandler Horn, courtesy of Grand Rapids Public Museum.

The Black Robe Chief

"People with white faces, people of the wooden vessel. Till the Black-Robe chief, the Pale-face, landed on the sandy margin. From his wanderings far to eastward, homeward now returned Iagoo." In the final scenes of the play, the priest arrives (representing civilization). A few scenes later, Hiawatha sails off into the sunset. The Ojibwa Indians are portrayed in this production as "good Indians," noble people of the ancient American past, who regrettably vanished. Americans involved in the pageant believed that the Ojibwa performers would benefit from participating by relearning their traditional customs. Some scholars have referred to these kinds of plays as "Indian minstrelsy." The performers realized that they were playing roles not based on the reality of their past, but they received income and respect in their community from the Americans who witnessed and produced the play. Photos by Grace Chandler Horn, courtesy of Grand Rapids Public Museum.

What did Indian imagery from postcards and road maps convey about Native people in the Great Lakes region, 1923-77

In front of wigwam, Postcard, 1925

This photo is representative of the kinds of images used on the postcards sold to local people and tourists. In the northern Great Lakes area, tourism became increasingly important after the automobile became a common means of travel and especially after 1930, when roads improved. Native people from the Great Lakes region were a popular subject for these postcards. The scene selected in this photo is a camp and wigwam, which suggests the remote and exotic past. But at this time, wigwams were used for certain group activities and, at other times, Native people lived in log or frame houses. Isabel and Batiste Gahbowh and Mrs. John Mink's mother, the individuals in this photo, may have camped at the Trading Post at Mille Lacs, MN in order to work or sell handwork. They are wearing everyday clothing, not "Indian" costumes. Photo by Edward A. Martinek, courtesy of Minnesota Historical Society

Big Injun Me, Postcard, 1937

This is a photo of Frankie Hanks at Mille Lacs Indian Reservation. The photographer has written "Big Injun Me" on the photo. Although the boy is dressed in modern clothing, the language used is a caricature that suggests the child is backward and uneducated, not "modern." Ojibwa children attended school at this time, and the boy would not have referred to himself as "big Injun me." Photo by Edward A. Martinek, courtesy of Minnesota Historical Society.

Chief Blowsnake, Postcard, Wisconsin Dells, ca. 1952

This is a photo of Blowsnake, a Ho-Chunk, at the Dells, a tourist attraction. He is dressed as a Plains Indian, in buckskin suit and war bonnet, and he is beating a drum. These kinds of performances and the mock Indian villages at the Indian attractions invited the tourist to return to the good old days of yore. Indians were situated in the past, not the present. Of course, in the 1950s Ho-Chunks lived in houses and drove cars similar to their non-Indian neighbors, and they had jobs in factories, the armed forces, and in other occupations. Photographer unknown, from H. H. Bennett Studio, photo courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society.

View from High Rock, Postcard, ca. 1970s

This photo is an example of a popular theme: a scenic view with Indians in the foreground. The woman is dressed as a Plains Indian, in the Princess role, and she appears to be part of the natural world. She looks from afar at the river boat, appearing cut off from the modern world. As time passed from the first to the last decades of the century, the disparity between ordinary experience of Native people and the public image increased, as these postcard images show. Tourists came to view these romantic images as portraits of "real" Indians. The postcards reinforced Indian stereotypes. Photographer unknown, from H. H. Bennett Studio, courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society, (85051).

Road Map of Wisconsin, Northern Illinois, and Northern Michigan, 1923

This widely used map design portrays the Indian as hanging on to a cliff, virtually a part of nature, while looking back on his homeland that he can no longer occupy. This is a "vanishing Indian" image, but in Wisconsin and northern Michigan in the early 20th century the Indian population was increasing and Indian communities were participants in the industrial economy as well as important to tourism. Drawing by William Mark Young (Newberry Library, RMcN Auto Trails 4C 66.55).

Road Map of Southwestern Michigan, 1941

This map is advertised as a fishing and hunting guide. It shows a modern sports fisherman and hunter, both White, contrasted with the Indian sitting on the ground drawing on rocks. The Indian has a "cave man"appearance, certainly not part of modern Michigan. At this time, many Native men from the region were serving in World War II and working in the war industry. They also served as guides for sports fishermen and hunters in the Great Lakes region. Socony-Vacuum Oil Co. (Newberry Library, RMcN AE 60.8.2).

Highway Map of Minnesota, 1958

The people of Minnesota are shown in modern, productive activities: farming, raising cattle, camping in a modern tent (as if they were tourists who contribute to the local economy). The "Indians"are caricatures, shown in front of a Plains tepee, doing a war dance, wearing feathered headdresses. They are not in or contributing to modern Minnesota. In reality, by this time, the tribes were working with their attorneys, engaged in legal struggles with the federal government in Washington, and the members of tribes were participating in the industrial economy, often in urban areas. Skelly Oil Co. (Newberry Library, Road Map4C G4141.P2 S5 1958).

Highway Map of Minnesota, 1977

This map has a generic design, showing images from around the country (Statue of Liberty, Liberty Bell, Mount Rushmore) that are patriotic or emblematic of industrial progress. The "Indian" imagery represents "primitive" life in the past: the Plains warrior with a bow and arrow and the totem pole (found in the Pacific Northwest). Minnesota Indians are not considered an important tourist attraction at this time. Phillips 66. (Newberry Library, Road Map4C G4144.M5 P2 1977 P45).

Americans also used long-ago Indian imagery to bolster national identity. Local pageants celebrated U.S. and state histories, incorporating Indian themes. Indian imagery was popular with groups trying to identify themselves with heroic past traditions—for example, Boy Scout organizations, hobbyists, and athletic teams. In reality, Indian Americans were participating fully in 19th and 20th century life, as consumers, employees, and as viable communities with their own cultural traditions, political operatives, religious leaders, and veterans of the armed services. They had revitalized their communities and cultural traditions. The Indian population in the region had increased dramatically. Non-Indian organizations that “honored” Indians by appropriating and revamping Indian symbols (headdresses, woodcraft, dancing, and so on) created “Indianness” that, in reality, did not represent Indian life, past or present.

What does a tour of Indian monuments in Chicago (1884-1978) reveal about national identity formation?

The Alarm, 1884

This statue is on the lakefront just south of Belmont Avenue. The sculptor was John J. Boyle. It was commissioned by Martin Ryerson as a memorial to the Ottawa Indians, with whom he had traded. Presumably, he viewed the Ottawas as "vanishing" or having vanished. The Indians in the group look wary, as if they were anticipating their extinction. The man is partially clothed, very muscular, and protective of the woman and child. The wild-looking dog provides an association with nature or the wilderness, as opposed to "civilization." The clothing is not what the Ottawas were wearing in the 1880s, and in Michigan they had towns and farms so they were living much like the American settlers. There are four stone relief works around the base called "The Corn Dance," "Peace Pipe," "Hunt," and "Forestry" -all associations with Indians who lived in the region long before the statue was installed. This statue reassures Americans that the disappearance of Indians was just and that it was destined to have happened. Research assistance and photo courtesy of Frances L. Hagemann.

The Rescue, 1893

This statue by the Danish sculptor Carl Rohl-Smith was commissioned by George Pullman and unveiled in time for the World Columbian Exposition in Chicago. It dramatizes the Indian wars in the Midwest region. Later, the statue stood near 18th Street and Prairie Avenue on the site of what was believed to be the attack on the evacuating occupants of Fort Dearborn. Named "The Massacre of Fort Dearborn," it was moved to the Chicago Historical Society. Protests by Indian activists resulted in a name change to "Potawatomi Rescue." In disrepair in the 1990s, it was moved to a warehouse. The bronze statue shows Mrs. Margaret Helm being attacked by an Indian with a tomahawk, while Black Partridge, a Potawatomi man, tries to save her. Later, she and her husband Lt. Linne Helm were released. The child at the feet of Black Partridge symbolizes the twelve children killed in the fight. A dying man, Dr. Voorhis, lies prone. Actually, Potawatomis from Wisconsin and northern Illinois participated in the attack and those living in Chicago tried to prevent it. At the Expo, the work served to contrast the supposed savagery of Indian life with American civilization, thus rationalizing the removal of Indians from Illinois and other parts of the Midwest. Research assistance and photo courtesy of Frances L. Hagemann.

The Signal, 1894

This statue is located on the lakefront just south of Belmont Avenue, but it was created for the World Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 by the sculptor Cyrus E. Dallin. It was purchased and donated to Chicago by Judge Lambert Tree, who referred to Indians as "simple, untutored children of nature," for whom there was "no future except as they may exist as a memory in the sculptor's bronze or stone and the painter's canvas." The sculpture was a monument to the "vanishing Indian," and it won a medal at the Expo. The sculptor Dallin was an American who studied art in Paris and was inspired by viewing Buffalo Bill's wild west show. The mounted Indian is dressed as a Plains Indian, the image that Americans considered representative of all Indians at the time. He appears to be on guard, anticipating the approach of civilization. At the Expo, images like this worked to glorify the inevitability and promise of American industrial progress. At this time, Native communities throughout the Great Lakes region were economically viable, though poor, and they had leaders and religious organizations, and their members had jobs. Research assistance and photo courtesy of Frances L. Hagemann.

The Bowman, 1928

This bronze statue and its mate "The Spearman" are in Congress Plaza at Michigan Avenue and Congress Parkway. They were cast in Yugoslavia by the sculptor Ivan Meštrović and commissioned by the B. J. Ferguson Monument Fund. This statue idealized and "honored" the Indian of the past, who was no longer a threat. Research assistance and photo courtesy of Frances L. Hagemann.

The Spearman, 1928

This statue and its mate "The Bowman" are nude, muscular males wearing Plains style headdresses. The horses they ride are European draft horses, not Indian ponies. The statue situates Indians in the past and presents Indian males as warriors, who no longer threaten the American public, so they appear as noble savages irrelevant to 20th century America. Research assistance and photo courtesy of Frances L. Hagemann.

The Defense of Fort Dearborn, 1928

This limestone relief sculpture by Henry Hering is on the southwest pylon of Michigan Avenue Bridge over the Chicago River. It was donated to the city by the B. F. Ferguson Monument Fund. The Indians are attacking William Wells, who was leading the escort for the Fort Dearborn occupants who were evacuating the fort during the War of 1812. Wells is portrayed as heroic, fighting against overwhelming odds. The Indians appear ferocious and brutish. Wells was disliked by his attackers, who thought (rightly so) that he had a history of treating them unfairly. In the War of 1812, the Indians (who had allied with Britain) were trying to defend their homes and their territory from the Americans who they believed were treating them badly and were determined to remove them from their homeland. This monument and the others that reference the evacuation of Fort Dearborn present a one-sided view of the situation at the time. The eventual American victory in the War of 1812 thus is represented as heroic and just. Research assistance and photo courtesy of Frances L. Hagemann.

Fort Dearborn, ca. 1971

This plaque commemorates the site of the original Fort Dearborn, near the base of a building on the southwest corner of Michigan Avenue and Wacker Drive. The Indian sits at the feet of the White man with the gun, so that the latter appears protective of and superior to the seated Indian. The occupants of this fort were evacuated during the War of 1812 and while they were traveling to the stronger Fort Wayne they were attacked by a Potawatomi war party. Survivors were protected by Indians and eventually ransomed. But the image on the plaque does not show an attack, but rather references a "protective" role of Americans toward Indian people. The plaque reinforces a national mythology that Americans treated Native people as well as possible. The plaque was donated by the National Society of Colonial Dames of America, Illinois. Research assistance and photo courtesy of Frances L. Hagemann.

Chicago Portage: Father Marquette, Louis Jolliet, and an Indian brave, 1989

This sculpture by Guido Rebechini is made of corten steel, which develops a rust-like patina. On the west side of Harlem Avenue just north of Interstate 55, it commemorates their passage through Chicago on their return from a voyage to Starved Rock in Illinois. The Chicago Portage became a national landmark in 1952 and this sculpture was installed in 1989. Marquette and Joliet are portrayed as heroic, in charge of the expedition. The Indian companion appears incidental to their efforts. In actuality, the anonymous Indian companion guided, handled the canoe, and interpreted for the two explorers. Of course, by 1989 the role of Indians in the exploration of the region was well documented by scholars, but in the popular imagination, they had played no constructive role. Research assistance and photo courtesy of Frances L. Hagemann.

Take a quiz? What’s wrong with this picture?

Image 1: Tippecanoe Remedy, ca. 1890

Photo by Brian Mornar, courtesy of the Newberry Library.

Image 2: Pontiac's War, 1894

Drawing by F. Opper in Bill Nye, History of the United States (Newberry Library, F 83 .64, p. 122).

Image 3: Indiana Pageant, Fort Wayne, IN, 1916

Photo courtesy of Brown University Library.

Image 5: Road Map, St. Paul and Vicinity, MN, 1963

(Newberry Library, Road Map 4C G4144.M5 P2 1963 P45).

Image 6: Fighting Braves of Michigamua, 1976

Photo courtesy of Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

Image 8: Cigar Store Indian, Traverse City, MI, 2007

Photo courtesy of Matt Stratton, mattstratton.com.

Answer Key

Image 1 - Tippecanoe Remedy, ca. 1890

Answer: This is one of many advertisements that used Indian imagery to sell patent medicines. Here, the strength of the battling warriors suggests the potency of the “Tippecanoe” remedy. The reference is to the 1811 battle between Tecumseh’s followers and American soldiers at a site in Indiana. Situated in “nature,” the Indian in these kinds of ads offers Americans a cure for rheumatism, headache, toothache, and so on. These “medicines” were marketed to appeal to the stereotype of Indians having knowledge of nature’s curative powers that other Americans lacked.

Image 2 - Pontiac's War, 1894

Answer: Nye writes: “Pontiac’s War was brought on by the Indians, who preferred the French occupation to that of the English. Pontiac organized a large number of tribes on the spoils plan, and captured eight forts. He killed a great many people, burned their dwellings, and drove out many more, but at last his tribes made trouble, as there were not spoils enough to go around, and his army was conquered. He was killed in 1769 by an Indian who received for his trouble a barrel of liquor till death came to his relief.” But Nye’s description distorts Pontiac’s life. The war against the British was promoted in 1763 by Pontiac and a Delaware prophet by the name of Neolin. The British had defeated the French and subsequently treated Native people arrogantly, refusing to participate in gift exchange, in trade with Native people. Their behavior convinced Pontiac and others that they would not treat them as friends and relatives, but as enemies. Neolin preached against the use of British trade goods, including liquor. Neolin subsequently had a vision experience in which he had a revelation that they should make peace with the British. By 1765 Pontiac was negotiating with the British to end hostilities, but there had been no decisive defeat, and villages tended to make their own agreements with the British. In any case, Pontiac was a war leader, not a civil chief, so in negotiating he lost stature and many of his followers drifted away. In 1769 he was in a Peoria village in Illinois country. In 1766 he had killed a Peoria man, and three years later that man’s nephew took revenge. He stabbed Pontiac in the back. There is no evidence that liquor was involved. Contrary to the point of view of Nye, the Native people were struggling over important issues in their quarrel with the British and Pontiac’s feat of uniting warriors from many different tribes was remarkable.

Image 3 - Indiana Pageant, Fort Wayne, IN, 1916

Answer: This program cover shows an Indian lurking in the forest, excluded from the modern, progressive town. The pageant, “The Glorious Gateway of the West,” was organized for Indiana’s centennial celebration. The theme was the disparity between Indian life and modern progress. The inevitability of progress was reinforced by the idea that land cessions that displaced Indians were legitimate (freely made). In the finale, all the participants marched into the “future,” which suggested that American society lacked social conflict based on race or class.

Image 4 - Scenic View, Postcard

Answer: These two boys are dressed as long-ago Indians. In this panoramic view, they seem part of nature. The boys seem disconnected from the modern world.

Image 5 - Scenic View, Postcard

Answer: The Indian child is dressed as a 19th century Plains Indian, carrying a bow. He and the attendant hold up their hands in a “How” sign, as if the child cannot speak English. The other two children are dressed as modern Americans. This imagery identifies “Indians” as people who live in the past, so contemporary Native people may be viewed as not “real Indians.”

Image 6 - Fighting Braves of Michigamua, 1976

Answer: University of Michigan students created an Indian-themed university men’s club, “Fighting Braves of Michigamua,” in 1901. The men chosen to belong were the top students, athletes, and leaders. Initiation involved a hazing ritual in which the new members were stripped, painted red and given pipes and “Indian names.” In effect, they invented an Indian tribe for themselves. The club members went into town dressed as Indians and they put on a yearly reenactment of the conquest of Michigan, reinforcing the idea that the Indians had left. At the same time, the image of the Indian warrior of the past reinforced the idea that club members were manly. By the 1970s, there began to be formal protests. In 1989, after conflict with the Michigan Civil Rights Commission, the university agreed that the club would drop its representation of Indians, and by 1997 this was done, except for the name “Michigamua.”

Image 7 - Squanto, mascot, ca. 1980

Answer: This caricature was the mascot of the Agronomy Department and featured as part of a departmental letter called “Squanto Speaks.” The mascot was retired in 1989. While Squanto is associated with providing corn and other food to the early colonists on the eastern seaboard, the portrayal of Squanto here is negative in that he looks both hostile and ridiculous, with a scowl and a large nose. Local Indian groups were bypassed when the department selected their mascot, which also suggests that it was generally, though erroneously, believed that Illinois Indians did not farm or were hostile to Americans.

Image 8 - Cigar Store Indian, Traverse City, MI, 2007

Answer: Cigar Store Indian sculptures mostly were popular in the late 19th century and used for commercial purposes to attract customers to stores that sold tobacco products. They also were used as decorations well into the 20th century, like the one in the photo. The statues usually had comic features and carvers created different types of statues: Chief, Maiden, Squaw, Hunter, Scout, and Brave. Some had names, such as “Black Hawk,” “Hiawatha,” or “Lo.” These statues portrayed Indians in stereotypical ways, for example, propagating the image of the stoic “wooden Indian.”

General Harrison and Tecumseh, lithograph, 1860

This illustration purports to represent a meeting between Tecumseh and William Henry Harrison at Vincennes in August 1810. Harrison had sent for Tecumseh to try to persuade him to agree to sign a treaty. Although Tecumseh is portrayed as large and menacing and Harrison and his companions as on the defense, in actuality one of Harrison’s officers made the first threatening move and Tecumseh then took a defensive posture. The tension was quickly resolved and there was no violence, but the message in the illustration is that Tecumseh and his warriors attacked the unarmed Harrison without provocation. Photo courtesy of Indiana Historical Society (P483).

Black Hawk War, 1894

This is an illustration by F. Opper for History of the United States. The author, Bill Nye, wrote that “The Black Hawk War occurred in the Northwest Territory in 1832. It grew out of the fact that the Sacs and Foxes sold their lands to the U.S. and afterward regretted that they had not asked more for them: so they refused to vacate, until several of them had been used up on the asparagus beds of the husbandman [killed].” Black Hawk is caricatured to look both ridiculous and treacherous. In actuality, the Sauk did not legitimately cede the land that Black Hawk was trying to retain. His village also tried to establish friendly relations and trade with the settlers, but was rejected. Nye was an anti-Indian humorist, whose work was popular at the time. Drawing by F. Opper in Bill Nye, History of the United States (Newberry Library, F 83 .64, p. 219).

Remnant of a Race, 1894

Newspaper Article about Winnebagos, January 19, 1894. The article describes the Winnebago as “pathetic,” degraded by reservation life. They are described as “once powerful” and a “remnant of a race,” now satisfied to get a few dollars annually from Uncle Sam. Big Hawk was the leader of a group forced out of Wisconsin in 1873. He later returned with his people and helped to perpetuate Winnebago community life in Wisconsin. In the drawing he is shown wearing a mix of “Indian” and “White” style clothing. Actually, the Winnebago bravely defied the removal policy and managed to stay in their Wisconsin homeland by working industriously, selling berries to settlers and doing other work. They opened up homesteads in the 1880s, where they had gardens. They also supported a school for their children. Ely Samuel Parker, Ely Samuel Parker Scrapbooks, 1828-1894 (Newberry Library, Ayer Modern MS Parker v. 12, p. 93).

On His Way, 1894

This is an illustration by F. Opper from History of the United States, by Bill Nye. Nye’s influential work presents Native people as not capable of adjusting to modern life. They are equated with the animals who have become or are becoming extinct. Nye wrote, “We can, in fact, only retain him [the Indian] as we do the buffalo, so long as he complies with the statutes. But the red brother is on his way to join the cave-bear, the three-toed horse, and the ichthyosaurus in the great fossil realm of the historic past.” In actually, in parts of the Great Lakes area, Native people were farming and participating in regional commerce. Many spoke English and were literate. Native American men also had served in the Union army during the Civil War. Drawing by F. Opper in Bill Nye, History of the United States (Newberry Library, F 83 .64, p. 319).

William Penn’s Treaty with the Indians, 1771

This painting by Benjamin West (1738-1820) is oil on canvas. It ostensibly represents and commemorates Penn’s founding of the province of Pennsylvania at a council with the Delaware in 1682. The meeting did not happen as depicted here. It actually is an allegory of colonial America’s acquisition of Indian land generally. In 1771 there was an uneasy peace between the Delaware, British, and the colonists who had seized Delaware land. But the painting shows a peaceful interaction in an idyllic setting. Indians are exchanging land for bales of cloth, while “civilization” arrives in the form of ships in the harbor and houses under construction in the forest. The Indians seem eager to make the exchange. The clothing is not uniformly of the Delaware style and there is no wampum displayed, which would have been a part of the treaty council. The painting erroneously suggests that the history of land cessions with the Indians was one of peaceful, willing compliance. West was born in America but trained as an artist in Europe. His figures are modeled after classical sculpture. The painting was commissioned by one of Penn’s descendants. Painting by Benjamin West, courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, gift of Mrs. Sarah Harrison (The Joseph Harrison, Jr. Collection), pafa.org.

Ojibwa Show Dancers, 1844

George Catlin (1796-1872) painted these nine Ojibwas when they came to London. This is a lithograph of the painting. Catlin began painting Indians in 1832. He wanted to educate the public about “noble” Native people untainted by civilization, and so he opened an exhibit of paintings and artifacts in New York City in 1837. He gave lectures there dressed in Indian clothing. Catlin took his show to London in February 1840, where he hired English actors to impersonate American Indians at war or “making medicine.” When a British officer, Arthur Rankin, arrived in England with the nine Ojibwas from the north shore of Lake Huron, they joined Catlin’s show, “Tableaux Vivants,” and Rankin and Catlin shared the profits of the very popular Ojibwa performance. Catlin’s show presented these Ojibwas as noble Indians and relics of the past, rather than people from mid-19th century society. They were dressed in traditional clothing and doing traditional dances, seemingly relics of a Golden Age. Actually, Ojibwas were working to adapt their way of life to new conditions in their homeland. These “show Indians” earned money for their families and conveyed a positive image of Indians to Europeans and Americans, which they thought would help them retain their communities in their homeland. Later Catlin took eleven other Ojibwas to Belgium. Some of them died on the tour. Below the painting of the group are pictograph signatures and portraits. Painting by George Catlin (Newberry Library, Ayer folio Art Catlin 2).

Andrew Jackson, the Great Father, ca. 1830

This engraving shows President Jackson as an imposing father figure who both manipulates and protects the vulnerable Indian people. In fact, Jackson defied the Supreme Court and disregarded treaties with Indians to remove them from their homes. The promises his representatives made at the councils where Indians agreed to removal went unfulfilled to a considerable extent. Photo courtesy of University of Michigan, Clements Library.

Pierre Menard, 1886

This statue by John H. Mahoney was the first piece of sculpture installed on the grounds of the Illinois capitol building in Springfield. Menard (1766-1844) was a French-Canadian fur trader, who also was the first lieutenant governor of Illinois. The partially clothed Indian looks up at Menard, who appears to look on him in a patronizing fashion. By 1886 the Indians effectively were removed from Illinois and were elsewhere, generally farming and living in dwellings similar to those of the settlers. This 8-foot bronze statue gives the impression that the Indians of Illinois were assisted and befriended by settlers, which was not true. Research and photo courtesy of Frances L. Hagemann.

The Death of Minnehaha, 1892

William de Leftwich Dodge (1867-1935) painted this oil on canvas work. It is an allegory for the “vanishing Indian.” The two partially clothed Indians (Hiawatha, on the right) are mourning and appear to be exhausted and weak. Hiawatha’s love, Minnehaha, has died during a famine. She is light skinned and naked, a doomed noble “princess” figure. The suggestion here is that Native people have disappeared. In fact, in the Great Lakes region, there were permanent Ojibwa reservations in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota and Dakota communities in Minnesota where Native people were adapting to a commercial economy. The artist, best known for murals, was born in the United States and trained in Europe. He draws on a tradition of European romanticism in this work. This painting is in the Philip F. Anschutz Collection, Denver, Colorado. Painting by William de Leftwich Dodge, photo courtesy of Wikiamedia Commons from American Museum of Western Art – The Anschutz Collection.

Illinois Pageant Program, 1909

This pageant, “An Historical Pageant of Illinois,” was written by Thomas Wood Stevens to benefit Northwestern University’s settlement house. It was staged in Evanston, Illinois in October 1909. Based largely on the work of Francis Parkman, the pageant dramatizes six episodes from Illinois history: Marquette and Joliet arrive; the Indians pledge loyalty to the French; Pontiac leads a rebellion (rejected by the Illinois Indians); George Rogers Clark and the Americans arrive; the fight at Fort Dearborn occurs; Black Hawk conducts a war in the 1830s. His second version was the Pageant of the Old Northwest, held in Milwaukee in 1911. Stevens knitted together his episodes with the poetic narrative of the Indian “prophet” White Cloud, played by a professional actor from Chicago, who watched his people disappear from history. The theme of Stevens’s pageants was the disappearance of Indians in Illinois and the inevitability of White conquest. These kinds of pageants were very popular in Midwestern towns during 1912-16. They were performed to boost the towns on various civic holiday celebrations: 4th of July, Old Home Week, county fair, high school graduation. Many showed Indians attacking Whites, but did not show Whites attacking Indians. Thomas Wood Stevens, Book of Words, An Historical Pageant of Illinois, 1909 (Newberry Library, 5A 5322).

Tobacco Advertisement, 1874