Honor Guard, Lac Vieux Desert Powwow at Watersweet, Michigan, 2008

1 2021-04-19T17:19:58+00:00 Newberry DIS 09980eb76a145ec4f3814f3b9fb45f381b3d1f02 8 1 Honor Guard, Lac Vieux Desert Powwow at Watersweet, Michigan, 2008. Photo courtesy of Lac Vieux Desert Band plain 2021-04-19T17:19:58+00:00 Newberry DIS 09980eb76a145ec4f3814f3b9fb45f381b3d1f02This page is referenced by:

-

1

2021-04-19T17:19:58+00:00

Cultural Identity

1

image_header

2021-04-19T17:19:58+00:00

Above: Clan Credentials, 1849. Henry R. Schoolcraft, Historical and Statistical Information, respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States, 1851 (Newberry Library, Ayer250.S3h 1851, vol. 1, Plate 60)

In the Great Lakes area, the local groups have shared a regional culture and also developed variations on this culture. The principal theme of regional culture is reciprocity, the belief that it is necessary and morally right to give something to get something in return. This idea has been expressed in the value placed on sharing with one’s relatives and gift-giving with in-laws and allies. Reciprocity extends to relations between humans and spirit beings. Over time, Native peoples of the region experienced the fur trade, treaty era, federal assimilation policy, and a modern resurgence of the acknowledgment of tribal sovereignty. All these experiences shaped contemporary life, as basic indigenous beliefs and values became the basis of cultural identity today.

Cultural identity is anchored in a deep emotional bond with the homeland (or locally-used territories). The Great Lakes region is woodlands with many lakes and rivers that enabled the indigenous people to survive. They have always obtained subsistence by hunting, fishing, and harvesting rice, maple sugar, and the other native plants. In the late 19th century, the concept of “trust land” (Indian land to which the federal government held title) became culturally associated with economic security and tribal sovereignty, and these ideas persist in the present. In the homeland are many sacred sites that have meaning and evoke powerful emotions for Native people.

Subsistence by hunting, fishing, and harvesting native plants has never been merely a means to survive. These are religious acts and vehicles for social cohesion. Survival has always been difficult and individuals have not been able to count on being successful in the search for game or other resources. Sharing among family members and “gift-giving” (including feasting) between groups of non-kin worked as a form of social insurance. Relatives had to work cooperatively in many economic pursuits. The common view was that the natural resources belonged to all the people and individuals were only entitled to use rights. Today, tribal resources, including income from tribally owned businesses, are available to all. The game animals and plant resources also allowed the indigenous peoples to participate in regional commerce from the time of contact with Europeans to the present. Today, traditional subsistence activity is culturally associated with tribal sovereignty, and tribes own businesses, including fish processing plants.

Listen to Dan Stone, Little River Ottawa, explain the importance of fishing rights to tribal sovereignty and cultural identity. Non-natives express their reservations.

Identity Through Fishing. Video courtesy of tdndavid/YouTube, 2007. View transcriptAnd, these activities are culturally iconic, so that tribes are working to revive the technologies associated with subsistence activity, for example as part of educational programs.

Listen to Reggie Cadotte from Lac Courte Oreilles explain how he is helping to perpetuate traditional ricing technology among Indian youth

Identity Through Ricing. Video courtesy of Indian Country TV, 2009. View transcriptFulfilling family obligations has always been central to identity, and “family” is defined in culturally distinct ways. With the exception of the Dakotas in Minnesota, clan membership is central to an individual’s identity in Indian communities. In Native belief, clans originated at the time of Creation, when the “Giver of Life” delegated power to various spirit beings, most of whom can appear in animal form. These spirit beings founded the original clans. Men and women belong to their father’s clan. Throughout the Great Lakes region, people from different groups could find allies among people who belonged to the same clan. Members of the same clan had a close bond, especially within a community.

Listen to John Low, Pokagon Potawatomi, explain how clan identity worked in the past and present

John Low on Potawatomi clan identity. Production by Mike Media Group, 2009. View transcript | View at Internet ArchiveIn Ojibwa clans, for example, the close bond between one’s “brothers” extended to brothers and sons of one’s father’s brothers. Also, the several clans in a village owed each other certain duties, so the clan organization also worked as a political organization with particular clans providing particular kinds of leaders. Over time, clan duties have changed, and today in many communities clan identity is representative of cultural identity for individuals.

Listen to Ernie St. Germaine, an Ojibwa from Lac du Flambeau, explaining the importance of clan identity

Ojibwa Clan Identity. Video courtesy of WDSE-Duluth/Superior, MN, 2002. View transcriptDakotas extend the kinship relationship to a wide network of relatives on both the father’s and mother’s sides, so that people in a community have many brothers, sisters, grandparents, and so on. Kinship obligations motivate people to cooperate and share.

Reliance on spirit helpers was important to the indigenous peoples of the region. Individuals sought visions to contact a spirit helper, and individuals had encounters with them in dreams. A relationship with a spirit helper meant that in return for gifts of food and tobacco, the spirit helper granted power to be successful in hunting, curing, and warfare. Group ceremonies, including the Medicine Lodge and Dream Dance worked on this principle. In recent times, peyote ritual provided a means to attain visions and prayers for success. Sometimes the acceptance of Christianity came as a result of a visionary revelation.

Beginning in the 1970s, there was a widespread social movement that promoted cultural “revival.” In every community, there were people (sometimes few, sometimes many) who still spoke the Native language, remembered important events in the past, and knew the subsistence technologies, songs, and ceremonies of their ancestors. They served as an important resource for individuals and communities seeking to re-energize cultural identity in the modern world.

Listen to Mille Lacs Ojibwas Jody Allen Crowe and Edward Minnema discuss their language program

Language and Identity. Video courtesy of WDSE-Duluth/Superior, MN, 2002. View transcriptDo you want to read about an instance of Ojibwa cultural revival?

The PARR [an anti-Indian fishing rights organization] rally witnessed one of the first public displays of modern cultural revitalization at Lac du Flambeau. For some time, a spiritual leader from Grand Portage in Minnesota, having dreamed that the unfolding conflict over fishing rights would become important, had been instructing the people of Flambeau in cultural practices that had been forgotten. A number of people were taught how to construct spirit poles, which are placed in front of one’s home. These are cedar poles about twenty feet long that are stripped of their bark and branches up to the last few feet; here medicines in the form of tobacco offerings, strips of colored cloth, and eagle feathers are often tied. A rock is often put at the base of the pole and tobacco offerings are placed upon it. Wayne Valliere remembered that this spiritual leader also taught the Flambeau singers four songs that they were to sing when they went to the PARR rally [in 1986].

Tom Maulson and a group of nearly one hundred people from Lac du Flambeau attended the rally in Minocqua. They brought a drum and an innovative ritual they later referred to as a friendship ceremony. The presence of the drum was significant to the tribal members; its use is a mode of establishing a relationship with the non-human persons who empower human beings. The drum that was brought to the rally was a descendent of the Drum Dance drum given to the people of Lac du Flambeau by the Bad River band who, in turn, received it from groups further to the west, who ultimately got it from their old rivals, the Dakotas. The Dakotas received it when a woman who was hiding in a lake from the U. S. Army was taken up into the spirit world and given instructions about the making and decorating of the drum and the songs and offices that went with it. Once the drum was made and its offices of belt carrier and pipe carrier filled, the soldiers came to dance. The drum thus represents an imaginative encompassment of one’s enemies, largely on one’s own terms.

What transpired that day was understood by the Flambeau people to have been influenced and guided by the spirits. As Wayne Valliere, a young man at the time, began to sing the first song, he noticed that all of the scowling protesters, adorned in blaze orange jackets (a symbol of anti-treaty sentiment), hats, and anti-Indian buttons, turned to look at him. Amid catcalls and hooting, he kept singing. Then the crowd stared up at the sky. “I saw them look up and I looked up and I saw an eagle making twenty-foot circles over the drum. He did that through the whole song, four times through. We sang three more songs and by the end those people were quiet. Then we walked through that whole town carrying that drum.”

For the singer, the eagle represented a validation of what he calls the ways of the ‘gete Anishinaabe’—“the ancient Indians.” Larry Nesper, The Walleye War, 2002, pp. 81-82.

Today, local communities or reservations devote resources to perpetuating oral traditions, their Native language, and activities they regard as traditional. They may introduce Native terms for their group to replace those terms used by Euro-Americans, for example Ho-Chunk rather than Winnebago, and Waswaaganing rather than Lac du Flambeau. Certain historical events may be reenacted as collective rituals of identity, as the Dakota do with a memorial ceremony for Dakota men executed after the 1863 Sioux Conflict.

Listen to John Low, Pokagon Potawatomi, discuss key symbols of Pokagon identity: the leadership of Pokagon, the Catholic mission, and subsistence technology

John Low on symbols of Pokagon identity. Production by Mike Media Group, 2009. View transcript | View at Internet ArchiveOne of the most important ceremonies where symbols of local identity are expressed and generate a sense of group distinctiveness is the community powwow. Here, there are gift-exchanges, the honoring of relatives, demonstrations of subsistence technologies, use of Native language, particular songs that have local meaning, and speeches that reinforce collective memory and cultural values.

Learn about the Pokagon Potawatomi community’s powwow

Potawatomi Powwow. Video courtesy of WNIT Public Television. View transcriptWoods and Stream, Keweenaw Bay L’Anse Reservation

Photo courtesy of Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission

Witch Tree, Grand Portage Reservation, Minnesota

This tree grows out of bare rock on the shoreline of Lake Superior. On tribal land, it is a sacred site for the Ojibwa. For generations they have left tobacco offerings there to the water spirits in the lake in order to gain protection when fishing and traveling on the water. In the Ojibwa language, the name for the tree means “spirit-little-cedar.” There are many other sacred sites in the region. And, of course, many of the mounds in the Midwest are sacred sites for Native people (Missaukee Earthworks, in Missaukee County, Michigan, for example). The photo was taken in July 2008 by Aaron C. Jors

Sugar Camp, ca. 1850

This watercolor painting by Seth Eastman shows a family camp in a grove of maple trees (the sugarbush). The house frames are covered by bark and the women have marked the family’s trees with an axe. They have made cuts in the trees and inserted wooden spiles. Containers catch the sap and then are emptied into barrels. The sap is boiled to make sugar. Mary Eastman, American Aboriginal Portfolio (Newberry Library, Ayer250.45.E2, 1853)

Canoe Maker, 1940

This Ojibwa couple is traveling to the Mille Lacs Trading Post, where they will sell the canoe. Much of the woodwork, sewing with hides and cloth, beading, and basketry was sold to tourists and resorts during the 20th century. This work was adapted for the market in many respects, but commercial handcraft also served to perpetuate the traditional technological skills that contemporary artists and crafts people need to sell art and to make outfits for powwows and other ceremonies. Photo courtesy of Minnesota Historical Society, Location no. E97.35r46, neg. 35791

Ho-Chunk Laborers Picking Cranberries, 1900

Winnebago (Ho-Chunk) families and groups of families worked as agricultural laborers throughout the year, moving from farm to farm with the seasons. Ethnographer Nancy Lurie has explained that these seasonal migrations paralleled the traditional seasonal subsistence migrations. They picked strawberries and cherries in the summer, moved to farms where they harvested corn and beans, then traveled to the cranberry fields in the fall. Photo courtesy of National Anthropological Archives, BAEGN4423

Ricing, Lac Vieux Desert Community

Katherine and Mark Sherman winnowing to separate the chaff from the grain. Today ricing can be a community-wide, rather than a family, affair, and whereas women used to be primarily involved, today men participate as well. Photo courtesy of Lac Vieux Desert Band

Sugar Bush Education

Sharon Nelis, Bad River tribal member, shows members of her family (Austin Nelis and granddaughter Rena LaGrew) how to tap sap from the maple tree. Families go to the sugarbush (a stand of maple trees) to collect sap to boil for syrup or, with more cooking, to make sugar candy. Photo by Sue Erickson, courtesy of Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission

Clan Credentials, 1849

This pictograph on bark was submitted to the President of the United States in January 1849 by the Ojibwa delegates who came to petition for the return of some land ceded in 1842 at the treaty of La Pointe. The delegation had not been authorized but these Ojibwas made such an impression with their native dress and their dancing that Congress agreed to pay their expenses. Each delegate identified himself by clan, as he represented his clan in the political negotiations. They sought to present their “credentials” as representatives for their people, and birch bark scrolls traditionally were used to record personal qualities. They brought with them an interpreter. In this drawing of the scroll by Seth Eastman we see: 1) the Crane Clan, represented by Oshcabawis, the leader of this village on the headwaters of the Wisconsin River. The eyes of the other clan animals are directed toward him (by lines) to show that they were of the same mind and the lines connecting their hearts indicate that they have a unity of feeling and purpose; 2) the Marten Clan, represented by the warrior Wai-mit-tig-oazh; 3) the Marten Clan, represented by the warrior O-ge-ma-gee-zhig; 4) the Marten Clan, represented by the warrior Muk-o-mis-ud-ains; 5) the Bear Clan, represented by O-mush-kose; 6) the Man-Fish Clan, represented by Penai-see; 7) the Catfish Clan, represented by the warrior Na-wa-ge-wun. The line from the forehead of #1 represents his progress or course, and the line going back to # 8 represents the purpose of the trip (to obtain the rice lakes, indicated by the # 8). The number 9 represents the path from the shore of Lake Superior to the village of the delegates and #10 represents Lake Superior. Henry R. Schoolcraft, Historical and Statistical Information, respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States, 1851 (Newberry Library, Ayer250.S3h 1851, vol. 1, Plate 60)

Offering Tobacco, ca. 2008

Larry Baker offers tobacco to spirit beings before the rice harvest as part of the reciprocity expected in subsistence activities. He sprinkles the tobacco in the water. Photo by Shanna Clark, alumna of Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwa Community College

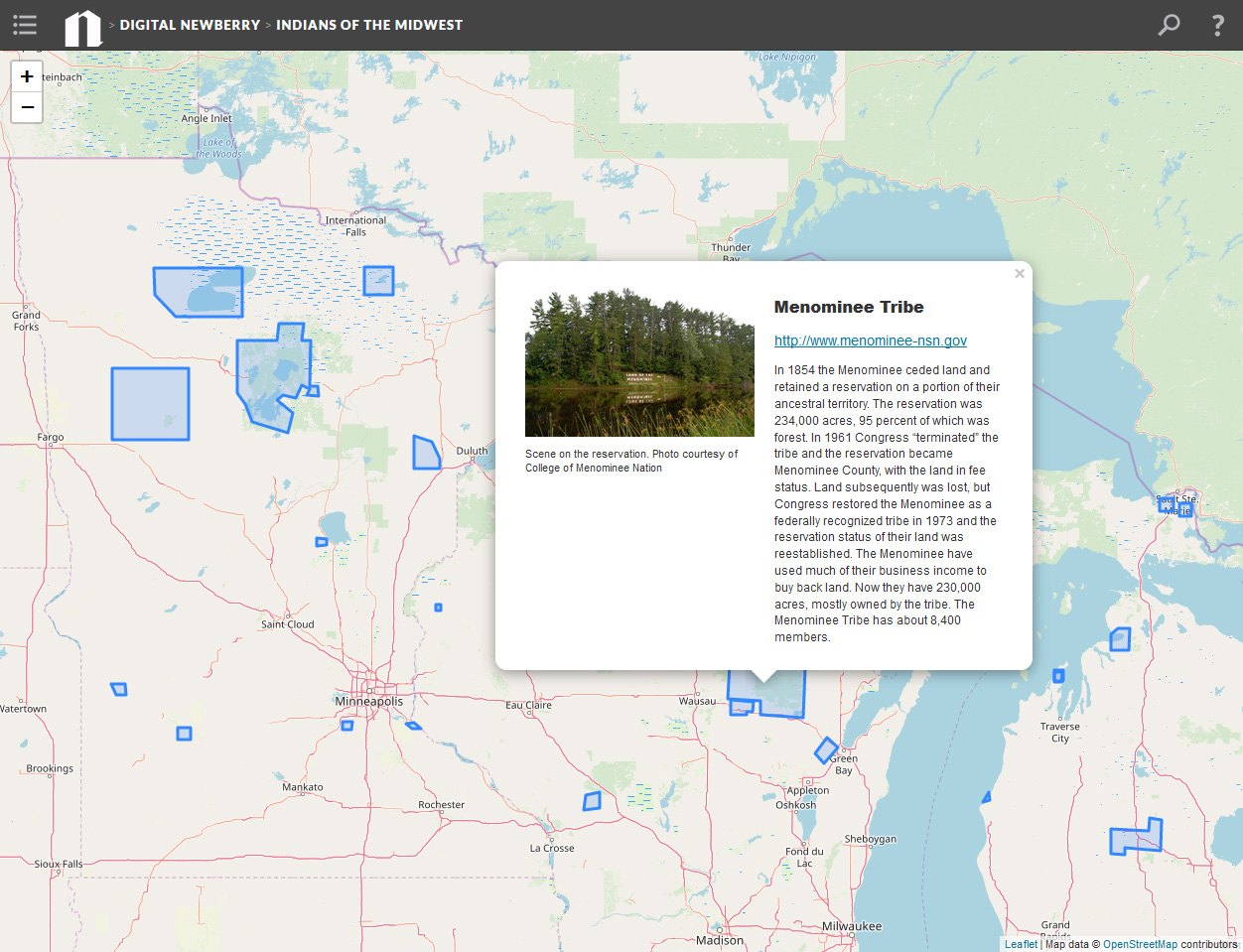

Honoring Veterans

These veterans are the Honor Guard at Lac Vieux Desert Powwow, Watersweet, Michigan, in 2008. They carry staffs signifying military experience and lead the dancers into the arena at the start of the powwow. Their service as an honor guard honors both them and veterans in general. Military service also has worked to revitalize traditional cultural practices throughout the 20th century. For example, men who served in World War I often were the focus of prayer ceremonies in the peyote church or other ceremonies, such as clan war bundle rituals. When they returned they were honored in victory dances, as were their ancestors in earlier times. These warrior traditions were reinforced and revived as a result of military service in World War I and II, and subsequently. Also, veterans often formed organizations that assumed political and ceremonial roles in their communities. Photo courtesy of Lac Vieux Desert Band

Ho-Chunk Peyote Leaders, ca. 1913

The “peyote church” attracted about half of the Ho-Chunk people, according to ethnographer Paul Radin. Most people joined after they were cured of an illness by peyote ritual. Many of the ritual components were comparable with traditional religion, but several Christian elements had been added by younger members through vision experiences. The church rituals or “meetings” took place weekly and more often in the winter and summer seasons when the Ho-Chunk Medicine Lodge ceremonies were also held. John Rave introduced the peyote church to the Ho-Chunk in 1893. He had been in Oklahoma during an emotional crisis, where he regained his health after participating in the ritual. Over time, several other leaders emerged in Wisconsin. Participants used a rattle and small drum, taking turns singing throughout the night, while they ate from the peyote plant. They also carried beaded staffs and eagle fans. The elements that were consistent with the Winnebago or Ho-Chunk religion were the offering of tobacco to the peyote spirit, the use of peyote as a medicinal plant, vision experiences, and singing as an act of prayer. Christian elements included readings from the Bible, baptism of new members in peyote water, and Christian symbolism at the “altar.” This altar included a mound (“Mt. Sinai”) at the end of the fire on which there was a Bible and the peyote plant. A cross was drawn on the ground in front of the mound. Members considered the peyote church to be helpful in their adjustment to the non-Indian world. The peyote church co-existed with the Medicine Lodge and Christianity, according to Radin. Paul Radin, The Winnebago Tribe, 1915-16 (Newberry Library, Ayer 301A2 1915-16)

American Indian Center, at its Present Location, Chicago North, 2009

The center opened at the instigation of the Chicago Indian community with assistance from philanthropic organizations. It was the first urban center in the country. At this time, Chicago was one of five original relocation cities that drew Indians from several states. Winnebagos (Ho-Chunks) and the Three Fires (Ojibwa, Ottawa, and Potawatomi) organized tribal clubs to reinforce a sense of community and culture. Urban Indians could identify themselves by their urban community as well as by tribe (or in lieu of tribe). These “urban Indians” were very influential in the treaty movement and cultural revitalization generally, and they maintained ties with their home communities. Today the center serves people from 50 tribes as a major gathering place where many activities take place—powwows, bingo, potlucks, family and community celebrations, and wakes. Photo courtesy of Flickr Creative Commons/Zol87

Test what you've learned about Indian cultural identity

-

1

2021-04-19T17:19:59+00:00

Sovereignty

1

image_header

2021-04-19T17:19:59+00:00

Above: Booth at a Dance. Photo by Orlando Cabanban (Newberry Library, Ayer Modern MS Seeing Indian, box 2, no. 46). View catalog record

By the 1930s, reform groups were criticizing Indian affairs policy by pointing to fiscal mismanagement and social injustice. In 1924, Congress had declared Indians to be citizens of the United States, yet they still were considered wards of the federal government and denied the right to vote in many states. The reform movement laid the groundwork for a major change in Indian policy when Franklin Roosevelt was elected president in 1933. His administration worked with Congress to pass legislation to allow Indians to participate in the recovery programs that benefited all Americans during the Depression.

In 1934 the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) ended the allotment of reservation land, permanently established trust title to Indian land, provided for the purchase of more land for Indians, established a credit program for Indian communities, and recognized the legitimacy of tribal governments. The new policy reaffirmed that Indians were tribal citizens, as well as U.S. citizens (just as other Americans had dual citizenship in other countries). Congress also provided for freedom of religion for Indian people.

Why was the IRA accepted by tribes and what provisions were in tribal constitutions?

Delegates from Minnesota Chippewa Tribe Meet with Federal Officials, January, 1940

Organized as a tribe consisting of six politically independent reservations, the Minnesota Chippewa sent their attorney with these delegates, the Tribal Executive Committee, to discuss matters that concerned all the reservations. They met with Assistant Commissioner of Indian Affairs, John Herrick. Before they organized under the Indian Reorganization Act, they had great difficulty arranging delegations and hiring attorneys. Left to right: John Hougen (attorney), Charles Roy (Bois Forte), Frank Broken (Leech Lake), Shirley McKenzie (credit agent, Bureau of Indian Affairs), Thomas Artell (White Earth), Sam Zimmerman (Grand Portage), M. L. Burns (Superintendent of Chippewa Agency), William Nickabaine (Mille Lacs). Photo courtesy of National Archives.

Works Progress Administration Project on Red Lake Indian Reservation, Minnesota, 1940

This Ojibwa crew was building a community center at Ponemah. These kinds of projects were launched nation-wide to relieve the economic distress caused by the Depression. Work was done on reservations as well as in other kinds of communities. Projects included forestry, road building, conservation, and construction of public buildings. The W.P.A. often used tribal leaders in these projects. Photo by Gordon Sommers, courtesy of National Archives.

Constitution and By-Laws of Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians, Wisconsin, 1936

The Indian communities in the Midwest already had governments in place at the time most accepted the constitutional governments established by the IRA, but the federal government largely ignored these leaders. The communities' acceptance of the new form of government reflected their hope that they would achieve home rule and greater influence over federal policy. The constitutional powers, although limited by a requirement that the secretary of the interior review many of the community leaders' decisions, included the right to obtain attorneys to pursue tribal interests, more control over their land and resources, and the right to determine their membership. The preambles of these IRA constitutions show the influence of federal officials, but also local understandings and concerns. The preamble of the Red Cliff Band's constitution emphasizes that the community is reestablishing their "tribal organization" and affirms the right of home rule and their treaty right to their land. One can read "tribal" to mean nationhood. Note that membership in the tribe depended largely on residency, rather than "degree" of Indian ancestry. The governing body was an elected nine-member tribal council, whose actions were subject to referendum by the community. The members of this council probably represented all the families in the community. (Newberry Library, Ayer 5 .U583 R31 1936).

Constitution and By-Laws of the Forest County Potawatomi Community, Wisconsin, 1937

The Forest County Potawatomi also intended to reestablish their tribal organization. Although the Potawatomi did not have a reservation set aside by treaty, their lands had been purchased and held in trust for them by the United States, and they expressed a commitment to conserving and developing their resources. In determining membership, they required that children of two members not residing on tribal land be of at least one-fourth Indian descent. If only one parent was a member who resided on the reserved land, the one-fourth blood requirement applied, as well. The governing body was the General Tribal Council, that is, all adult members. The Forest County Potawatomi adult members numbered not more than 120. (Newberry Library, Ayer 5 .U583 F71 1937).

Constitution and By-Laws of the Bay Mills Indian Community, Michigan, 1936

The Bay Mills Indian Community emphasized the protection of their property and resources. Membership in 1936 depended on residency and allowed for the enrollment of members of the Sault Ste. Marie Band living nearby but off the reservation. The residency requirement gave support to their commitment to a close-knit community. The constitution established that the governing body was the General Tribal Council, that is, all the adult members. The adult membership was less than 200. (Newberry Library, Ayer 5 .U583 B35 1936).

Constitution and By-Laws of the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community, Michigan, 1936

In this community, there were three small politically independent groups who organized "as a tribe." United, they had as many as 750 adult members. The federal government's recognition of their tribal status gave them more control over their affairs. The governing body was a twelve-member elected council representing the three groups. (Newberry Library, Ayer 5 .U583 K26 1937).

Constitution and By-Laws of the Lower Sioux Indian Community in Minnesota, 1936

In their constitution, the Lower Sioux promised to support the constitution of the United States and that of Minnesota, which may have been an attempt to address the lasting animosity from the “Sioux Conflict.” Membership was offered to resident Dakotas enrolled on other Sioux reservations upon their transfer to the Lower Sioux community. In what was perhaps another effort to reassure the federal government, members who received land assignments from the Community Council were required to cultivate it. The Lower Sioux also affirmed their treaty rights to hunt and fish. The governing body was a five-member Community Council whose actions were subject to a referendum by the eligible voters. These referendums supported the ideal of consensus decision-making. In later years, all these reservation communities revised their constitutions. (Newberry Library, Ayer 5 .U583 L917 1936).

Minnesota Chippewa Tribal Headquarters, Cass Lake

Today this overarching tribal organization provides services and technical assistance to six Ojibwa reservations in Minnesota. Since its organization in 1934, it has expanded. For example, it administers educational projects for urban tribal members. The members of the six Ojibwa bands also are members of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe. Photo courtesy of Minnesota Chippewa Tribe.

Indian people subsequently pressed for more control over their communities and more personal freedom. Indian veterans of World War II introduced more assertive strategies in their communities and played an important role in the establishment of the National Congress of American Indians in 1944. This organization lobbied in Washington DC for Indian rights.

Do you want to learn more about veterans?

Menominee Sailor in World War II, 1943

Dan Waupoose poses for U.S. Navy photographer while wearing a feathered headdress. In September 1940 the Congress enacted the draft and declared war in December 1941. 42,000 Indians were eligible for the draft. The B.I.A. unsuccessfully tried for an All-Indian Division of Indian soldiers. Indians were assumed to be good fighters and integrated into White units. During World War II 25,000 Indian men served and several hundred Indian women joined the service as WACS and WAVES. In the Army Signal Corps, Oneida, Ojibwa, and other soldiers used their native language in code work. Indian soldiers were recognized for their distinguished service in the Army, Navy, Marines, and Army Air Corps. Veterans later became important participants in tribal government and in political activism generally. Photo courtesy of National Archives.

Visiting Veterans Memorial, Leech Lake Reservation, 2008

These students from the tribal college are visiting the memorial as part of learning about the history of their community. They will write about their experience. Photo by Mark Lewer, courtesy of Leech Lake Tribal College.

Honor Guard, Lac Vieux Desert Powwow at Watersweet, Michigan, 2008

These veterans carry staffs signifying their military experience. They lead the dancers into the arena at the start of the powwow. In doing this, they are honored for their service and, at the same time, they honor all the veterans. Photo courtesy of Lac Vieux Desert Band.

Exhibit Honoring Veterans

This is part of a National Museum of the American Indian traveling exhibit, "Native Words, Native Warriors," which honors American Indian Code Talkers from more than twelve tribes, who served in World War I and II. Photo courtesy of Match-e-be-nash-she-wish Band of Pottawatomi.

By the 1950s, responding to a backlash among their constituents, Congress tried to reverse the policy of supporting tribal communities. New legislation provided for the termination of the trust relationship if Congress decided that a tribe no longer needed protection. In such cases, funds could be withdrawn for tribal health and education. And the trust title to land protected Indians from the loss of land to state and local taxes. In 1954, Congress terminated the Menominee, who had a lumber business that was competitive with non-Indian lumber interests.

Congress also passed legislation enabling Michigan and Wisconsin to extend legal jurisdiction over Indian reservations without tribal consent. Many Indian children were removed from their communities and sent to non-Indian foster homes. And, a national “relocation” program promoted the resettlement of reservation Indians in cities, including Chicago, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, and Grand Rapids.

What has community life been like for urban Indians since relocation?

Social Dance at American Indian Center Powwow, 1968

Indian centers began to appear in cities after the start of the relocation program. A major activity in the early days of the center in Chicago was the powwow. It was a multi-tribal celebration of various styles of dancing and songs. The dance shown here was a couple dance, popular with young people. Photo by Orlando Cabanban (Newberry Library, Ayer Modern MS Seeing Indian, box 2, no. 11).

American Indian Center Powwow, 1968

The powwow, which brought together singers from many tribes, helped diffuse different styles and contributed to creativity. These singers sit around the large drum, which they beat in unison. Facing the camera are Sam Sign and Archie Blackowl. The first annual American Indian Center powwow began in 1954. In the 1960s, monthly powwows drew up to 500 people. Photo by Orlando Cabanban (Newberry Library, Ayer Modern MS Seeing Indian, box 2, no. 19).

1958 American Indian Center Dance Club, Chicago

The club traveled widely, encouraging powwow activity, especially in urban centers. Top row, l to r: Harry Funmaker, Linda Benson, Ernest Naquayouma Sr., Ruby Keahna Funmaker, Ernest Naquayouma Jr., Norma Bearskin Stealer, Ben Bearskin Sr., Barbara Keahna, James Passafume. Middle row, l to r: Dennis Keahna, Pauline Logan Funmaker, Ramona Naquayouma, Stella Johnson, Lillian Naquayouma, Kenneth Funmaker. Bottom row, l to r: Bernadette Miner, Avery Lonetree, Laura Miner, Danny Miner. Photo by Dan Battise (Newberry Library, Ayer Modern MS Seeing Indian, box 1).

Booth at a Dance

At the Indian Center in Chicago, artists sold their work and people sold food, usually to raise money for the center. Photo by Orlando Cabanban (Newberry Library, Ayer Modern MS Seeing Indian, box 2, no. 46).

Basketball Players at the American Indian Center in Chicago

The center encouraged children to come there for educational services, participation in clubs, and opportunities to play sports. Photo by Orlando Cabanban (Newberry Library, Ayer Modern MS Seeing Indian, box 2, no. 31).

1960-61 Boys' Basketball Team, with Cheerleaders, American Indian Center at Chicago

The team had a fan base among Indians in Chicago. They played against teams on reservations and other urban areas. Photo by Dan Battise (Newberry Library, Ayer Modern MS Seeing Indian, box 1, no. 8).

Girls' Basketball Team

The girls' team also was popular. Photo by Dan Battise (Newberry Library, Ayer Modern MS Seeing Indian, box 1, no. 31).

Canoe Race

The Canoe Club at the American Indian Center in Chicago was active in the Chicago area, paddling on the Great Lakes in the company of crews from the reservations, and the members traveled to other regions to participate in races. Shown are Art Elton, Tony Barker, Archie Blackelk, and Paul Goodiron. Photo by Orlando Cabanban (Newberry Library, Ayer Modern MS Seeing Indian , box 2, no. 17).

Day Camp Outing

These children are attending a summer camp sponsored by the American Indian Center in Chicago. Photo by Orlando Cabanban (Newberry Library, Ayer Modern MS Seeing Indian , box 2, no. 18).

Family's House in Chicago

For families like this one, the American Indian Center in Chicago provided a place to make social ties, reaffirm traditional Indian identity, develop leadership potential, and obtain social services. Although the center's activities were multitribal, tribal clubs (like the Winnebago Club and the Council of Three Fires) were organized. The first center opened in a rental space downtown in 1953. In 1963, the center relocated to uptown Chicago, where most of the Indians lived, and in 1966, the center moved to its current location at 1660 W. Wilson Avenue. Leaders at the center offered criticism of termination policy and the faulty implementation of the relocation program. The center was funded by private donations. Photo by Dan Battise (Newberry Library, Ayer Modern MS Seeing Indian, box 1).

American Indian Center, Chicago, 2009

The center opened at the instigation of the Chicago Indian community with assistance from the American Friends Service Committee and other philanthropic organizations. It was the first urban center in the country. At this time, Chicago was one of five original relocation cities. Illinois was without a large in-state reservation, so the center drew Indians mostly from outside the state. Today the center serves people from 50 tribes. The 2010 census counted almost 11,000 Native people in Chicago. The American Indian Center has academic, health, and social service programs. It is a major gathering place for Indians in Chicago, where many activities take place-powwows, bingo, potlucks, family and community celebrations, and wakes. The Trickster Gallery is the only Native operated arts institute in Illinois. It offers gallery space, tours, and workshops. The center operates with a board of directors, elected by the Chicago Indian community. Photo courtesy of Flickr Creative Commons, user Zol87.

Minneapolis American Indian Center

The wood collage is by Grand Portage Ojibwa artist George Morrison. The center was founded in 1975. It offers employment training, senior citizens assistance, youth programs, and health and wellness services. The center operates an art gallery and otherwise supports Indian cultural traditions. The 2010 census counts almost 9,000 Native people in Minneapolis-St.Paul. Photo courtesy of Randy Croce.

Federal policy changed again in the 1960s, when Democratic administrations extended War on Poverty programs to Indian communities, revitalizing tribal governments in the process. The American Indian Civil Rights Act was passed in 1968, which, among other things, required states to obtain Indian consent before assuming jurisdiction on Indian land. Many communities started or elaborated on “powwows,” rituals that served as expressions of Native pride.

View powwow dancing

Powwow. From Since 1634: In the Wake of Nicolet. Video courtesy of Ootek Productions, 1993. View transcriptIn 1968, the American Indian Movement (AIM), a new organization whose membership was young and often from urban areas, began to use public demonstrations to publicize the social injustices that Indians still faced.

Do you want to learn more about AIM?

Dennis Banks, New York, 1967

Banks, one of AIM's original members, joins other demonstrators against the war in Vietnam. Banks grew up on Leech Lake Reservation, and after years in Indian boarding schools, service in the Air Force, and a stint in prison, he obtained employment in the Honeywell Corporation in Minneapolis. He and Clyde Bellecourt founded AIM in 1968 to advocate for Indians in the Minneapolis area. They organized to monitor arrests of Indians in an effort to stem police brutality. AIM expanded its activities and achieved national prominence, eventually organizing a march on Washington to protest the United States's treatment of Indians. Photo by Dave Tyson.

American Indian Movement Demonstration, ca. 1978-83

Clyde Bellecourt (White Earth Ojibwa) is speaking to a rally to stop the potential closing of Little Earth of United Tribes, a primarily American Indian housing development in Minneapolis. Bellecourt was one of the original founders of AIM in Minneapolis. He attended Indian boarding schools, served time in prison, and then obtained employment in Minneapolis. Most of the initial members of AIM were Ojibwa, from urban and reservation areas. Photo courtesy of Randy Croce.

Political Rally, 1982, with AIM Participation

This was a march by several progressive groups in Loring Park, Minneapolis. Clyde Bellecourt holds the microphone. Below him on the far left is Bill Means and in the lower right, Floyd Westerman. AIM made alliances with churches, progressive attorneys, and liberal groups, especially around the issue of the nuclear power plant next to the Dakota Prairie Island Indian Community on the Mississippi River. Photo by Randy Croce.

AIM at International Indian Treaty Conference

The theme of the conference was unity among Native people all over the world. The conference was held on the White Earth Reservation in 1981. Vernon Bellecourt is seated on the left. Photo courtesy of Randy Croce.

Listen to Dennis Banks discuss the formation of AIM

AIM. Video courtesy of WDSE-Duluth/Superior, MN, 2002. View transcriptIn the 1970s, Indian advocacy and public pressure led to a new emphasis on Indian sovereignty. Both Congress and the Supreme Court acknowledged that the federal government was bound by its treaties with Indian tribes and that tribes had the right of self-government and economic self-sufficiency. In 1973, Congress restored the Menominees’ tribal status and put their land back in trust.

Listen to Menominees explain how they regained their status as a federally recognized tribe.

Menominee Restoration. From Since 1634: In the Wake of Nicolet. Video courtesy of Ootek Productions, 1993. View transcriptWith support from President Richard Nixon’s administration, in 1975, Congress provided that tribal governments, not the federal government, would administer federal services and programs. Tribes took over responsibility for child welfare, ending the adoption of Indian children by non-Indians. Tribal programs employed Indians and tried to provide more culturally appropriate services.

What kinds of services do tribal governments provide?

Head Start Program, Leech Lake Reservation

On this occasion the tribe's Gaming Department donated toy log cabins to the children in the program. Profits from tribal businesses help support the Head Start program, which also receives funds from the tribe's contracting relationship with the federal government. The Head Start program stresses culturally relevant activities. At Leech Lake, the tribe owns three casinos and two hotel-resorts. Income is used to support many community projects and programs. The logos of the casinos reflect the Ojibwa heritage, particularly close relations with the natural world. Photo courtesy of Gaming Department, Leech Lake Reservation.

Language Class at the Waadookadaading School in the Lac Courte Oreilles community

Brian McInnes teaches the Ojibwa language at a language immersion school, where children spend the day hearing only the Ojibwa language. The Ojibwa community supports encouraging the Native language because it is intimately connected to indigenous knowledge about the world. Photo courtesy of Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC).

Clinic, Menominee Reservation

The clinic, which was the first Indian-owned and operated clinic in the United States, opened in 1977, and since then it has been expanded several times. The tribe gives significant financial support to the clinic and the health programs it undertakes. Indians without health insurance are treated without charge. The clinic provides medical, dental, and optical services and operates a pharmacy. Photo courtesy of College of Menominee Nation.

Forestry Work, Fond du Lac Reservation

Here, a tribal employee is managing a prescribed burn. When conditions are right, the forestry program does this to reduce the amount of fuel that would otherwise support fires, to open up areas to wildlife, or to renew habitats for plants like blueberries and trees like the white pine. The tribe's forestry program includes fire prevention education, maintains the health of the forested reservation land, and suppresses wild fires within or near the reservation, as well as assists on other fires in the region. Photo courtesy of Forestry Department, Fond du Lac Tribe.

Health Department Wellness Program at work, Match-e-be-nash-she-wish Band

In 1954, Congress created the Indian Health Service (IHS). Before this, agencies might have a doctor assigned to cope with all health issues. The Department of Health and Human Services oversees the Public Health Service for all Americans. The IHS is a subagency charged with providing medical and hospital care for Indians who are members of federally recognized tribes. The IHS is seriously underfunded despite the fact that the mortality rate is higher and life expectancy lower for Indians than the U.S. average. Diabetes and tuberculosis mortality is also significantly higher, as is the suicide rate. Tribes contract with HHS to provide health care and preventive services like the Match-e-be-nash-she-wish Wellness Program, in an effort to improve health conditions. Photo courtesy of Match-e-be-nash-she-wish Band of Pottawatomi.

Bois Forte Community Center

This center has meeting rooms, fitness equipment, and space for activities. The Tribe began obtaining loans and grants from the U. S. Department of Agriculture Rural Development Program in the 1990s. This program works to improve sanitation (water and sewer services), infrastructure, and public facilities, and it was responsible for this center. Photo courtesy of United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

Sault Police Car

Tribal governments develop law and order codes and contract the operation of police departments from the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Tribal governments are responsible for overseeing the work of the police force. Photo courtesy of Daryl McGrath

In 1978, tribes not recognized by the federal government gained opportunities to have their tribal status legalized, and Congress increased funding for education.

What do tribal colleges do?

College of Menominee Nation Campus

The college began in 1993 in a small house, moved to a trailer, and over the years expanded to what it is today. It is one of 36 tribally controlled community colleges in the United States. Fully accredited, it offers academic and vocational programs and infuses the curriculum with Menominee language and culture studies. The college provides job placement service and its students can transfer credits to the University of Wisconsin. Tribal colleges, like this one, have relatively small student bodies, which benefits Native students by increasing graduation rates and success at four-year institutions. At tribal colleges, the Board of Directors, administration, and many faculty members are Indian. Photo courtesy of College of Menominee Nation.

Graduation, College of Menominee Nation

Some graduates continue their education and others enter the job market. The majority of students at tribal colleges are women, who have been able to improve their economic circumstances through education. Tribal colleges are major employers in Indian communities and they provide job training and consultation for economic development. Photo courtesy of College of Menominee Nation.

Drama Class, College of Menominee Nation

These students performed a dinner theatre production of a play. Many people from the community attended the performance, held at the tribe's casino complex. The play reflected on Menominee history. Photo courtesy of College of Menominee Nation.

Sculpting, Leech Lake Tribal College

Student Ketta Flores is following Ojibwa tradition by learning to sculpt. Leech Lake Tribal College offers a two-year liberal arts program. Accredited, it provides traditional academic subjects, Native studies, and vocational courses. The college also offers an honorary degree for elders as part of a life-long learning opportunity and an effort to support the role of elders in contemporary life. Tribal colleges, like this one, come out of what has been called "the tribal college movement," which developed Indian leadership, encouraged Indians to regain control of their children's education, improved access to higher education, and promoted cultural revitalization. The movement emphasized using Native cultural traditions as a framework for academic rigor and as a means to address poverty in Indian communities. Photo by Mark Lewer, Courtesy of Leech Lake Tribal College.

Making moccasins, Leech Lake Tribal College

Student Supaya Therriault makes moccasins as a classroom activity. This project, as well as sculpture projects, help to support the college's goal of including Anishinaabe language and culture in the curriculum. Photo by Mark Lewer, Courtesy of Leech Lake Tribal College.

Biology Class, Leech Lake Tribal College

Casondra Gagner works on an assignment. Photo by Mark Lewer, Courtesy of Leech Lake Tribal College.

Class on Plant Identification, Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwa Community College

Instructor Larry Baker points out and discusses plants during a class. The college was established in 1982. Accredited, it offers post-secondary and continuing education programs. Tribal colleges are underfunded and do not receive state funding as other community colleges do; yet, at least 25 percent of the students are non-Native. Most Indian community colleges admit non-Indians and provide them with educational opportunities they might not otherwise have. Photo by Shanna Clark, courtesy of Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwa Community College.

Class on Indigenous Foods, White Earth Tribal and Community College

Here members of the class are tapping maple trees to obtain sap that will be made into syrup and cakes. Photo courtesy of White Earth Tribal and Community College.

Tracking Animals, White Earth Tribal and Community College

Here, in the study of zoology, instructors use indigenous "ways of knowing" to complement other pedagogies. Classes held in the forest accomplish the same objective. This program reflects the goals of the tribal college movement. Photo courtesy of White Earth Tribal and Community College.

The Supreme Court affirmed tribes’ exemption from state taxes and exempted tribal citizens living on reservations from state property and sales taxes. In the 1980s and 1990s the Court also affirmed the Ojibwas’ treaty rights to hunt and fish on ceded lands and the right of tribes to operate gaming establishments on trust land without state regulation. In the wake of the support for tribal sovereignty and increased sensitivity to Indian issues, signs of a backlash began to emerge.

Interactive map: Explore federally recognized tribes

Ojibwa Home, 1935

This photo was taken at Grand Portage. Indian families struggled economically during the early 1930s. Photo courtesy of Minnesota Historical Society.

WWII Indian Worker

Kay Lamphear, Defense Plant Worker at Allis Chalmers Manufacturing Company in Wisconsin, 1942. This Indian woman operated a punch press, machining diaphragm blades for airplane engines. During World War II many Indian women and men worked in defense plants and the airplane industry as riveters, machinists, and inspectors. The tribes also purchased war bonds or donated money to the war effort. Photo by Ann Rosener, courtesy of Library of Congress.

Jingle Dress

About the time of World War I, when the Spanish influenza epidemic spread through reservation populations, an Ojibwa girl became ill. Her father sought a vision to save her life. He received a message from spirit beings that if she wore a particular dress and danced to particular songs, she would recover. She followed these instructions and regained her health. Subsequently, she founded the first Jingle Dress Society, which was associated with curing and with women curers. In Ojibwa belief, supernatural power moves through the air, for example, through sound, which is why singing is an act of prayer. The jingle dress has rows of metal cones that rattle when they move, conveying sound in rhythmic accompaniment to the songs. Originally, the cones were made from round snuff can lids. So this was a ceremonial dress and the dance was a prayer for healing. People gave gifts of tobacco to the dancer as a request for her to pray for the recovery of people who were ill. In the 1980s, as songs and dances were revived across Indian country and transferred from tribe to tribe, the Jingle Dress Dance became widespread and today is one of the contest dances in powwows like the one in Minneapolis (shown above). For Ojibwa, it remains associated with ceremonial healing. Photo courtesy of Little Earth of United Tribes, Minneapolis, MN.

Zoar Ceremonial Hall

This building and the adjacent lodge (note the frame at the side of the building) are used by the members of the Zoar community on the Menominee Reservation. Traditional ceremonies gained participants after the restoration of the Menominee reservation community. Photo by Dale Kakkak, courtesy of College of Menominee Nation.

Menominee Restoration

In 1954 the Menominee were self-supporting, even paying the salaries of federal government employees. They supported the Catholic hospital, schools, and their own utility company from the profits of their lumber business and a legal settlement they received. Congress pressed the Menominee to agree to termination, that is, relinquishment of the trust status of their land and property. Ignoring Menominee resistance, Congress put termination into effect in 1961. What followed was a major social and economic decline. Their capital was dissipated because the federal government forced them to pay the costs of termination. The tribe had to sell their utility company and close the hospital. With the loss of medical care, the community experienced a tuberculosis epidemic. Non-Indians took over the management of tribal resources, while tribal members became “stockholders” in Menominee Enterprises, which worked to sell Menominee land to non-Indians. By 1970, DRUMS, an advocacy group that worked to reverse termination, emerged, and led demonstrations, obtained legal counsel, and lobbied in Washington DC. Ada Deer (shown at right), a Menominee with experience in dealing with the federal government, directed the lobbying effort in Washington. In 1973 Congress was persuaded to pass the Menominee Restoration Act and President Nixon signed it. The Menominees reorganized their tribal government, got reservation land restored to trust status, rebuilt the lumber mill, built a health facility, and embraced the revitalization of traditional religion. Photo courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society.

Ojibwa Houses on Bad River Reservation, built by HUD during the 1960s

Compare these houses to the one above (Ojibwa Home, 1935). Since the 1960s Indian housing has improved significantly, after the federal government began to support housing programs on reservations and elsewhere. The Indian Health Service, Bureau of Indian Affairs, and Housing and Urban Development began work to improve sanitation (for example, installing indoor plumbing and monitoring water quality), repair homes, and construct homes for rent, purchase, or elderly occupation. After 1975, tribes could contract with the federal government to supervise home improvement and construction projects and they aggressively sought such contracts. Photo courtesy of Charlie Rasmussen, 2011.

Test what you've learned about Indian sovereignty