Habit of an Ottawa Indian

1 2021-04-19T17:19:59+00:00 Newberry DIS 09980eb76a145ec4f3814f3b9fb45f381b3d1f02 8 1 Habit of an Ottawa Indian. Photo courtesy of Mackinac State Historic Parks Collection, Michigan plain 2021-04-19T17:19:59+00:00 Newberry DIS 09980eb76a145ec4f3814f3b9fb45f381b3d1f02This page is referenced by:

-

1

2021-04-19T17:19:58+00:00

Fur Trade

1

image_header

2021-04-19T17:19:58+00:00

Above: A general map of New France commonly call'd Canada. Louis Lahontan, New Voyages to North-America, 1703 (Newberry Library, Graff 2364, v. 1). View catalog record

In the early 17th century, French traders began to use Huron (or Wyandot) middlemen to trade with the Native peoples in the Great Lakes region. Native people belonged to several “ethnic” groups. The members of an ethnic group (for example Ojibwa or Menominee) spoke the same language and shared a common history and identity, but did not all live in the same community or recognize the same leaders.

What did European mapmakers know?

The French came for furs, especially beaver pelts used to make felt hats. The French succeeded because they adopted the technology and accepted the social customs of Native people. These Frenchmen traveled by birchbark canoes along old trade routes, using Indian guides and interpreters, learning Indian names for rivers and villages, and surviving on Indian corn. They established trade relationships with villages by participating in well-established rituals. They were adopted as kinsmen by a village leader in the calumet ceremony.

They also married Native women and became in-laws. They brought gifts to important people when there was a death. Gift-giving helped maintain the alliances between French traders and Native leaders. Native people eagerly sought the European trade goods because these items often worked better, lasted longer, and saved labor. Indian villages relied on the few French posts in the region or dealt with independent traders who reached their villages.

New Voyages to North-America, Mackinac Region

This map shows a settlement of French, Huron, and Ottawa on the south shore of Lake Huron. Note the importance that fishing for whitefish receives. Jesuit missionaries (B) accompanied the French traders everywhere. The Huron village (C) and Ottawa village (E) not only depended on trade in furs. They grew crops for themselves and for the French (D). Louis Armand, Baron de Lahontan (1666-1715), was in the French military in New France and traveled throughout the Great Lakes area. His geographical errors (for example, the "Long River") influenced cartography for 100 years until the Lewis and Clark discoveries. Louis Lahontan, New Voyages to North-America, 1703 (Newberry Library, Graff 2364, v. 1).

New Voyages to North-America, General Map of New France

This map shows where French traders were established by the end of the 18th century. Montreal was a major trade depot, and note LaSalle's fort on the southeast shore of Illinois Lake and Fort Crevecoeur, established by La Salle in 1679, on the Ilinese [Illinois] River. The British presence is farther east. The dispersal of the Huron is reflected on the map, as well as the important middleman role of the Ottawa (Outaouas). Note the major waterway named after the Ottawa. The Illinois-speaking groups were very powerful at this time-note that what is now Lake Michigan is "Ilinese" [Illinois] on the map. But the map has little detail on the numerous Illinois villages-only "Ilinese" and "Tamaroa" are mentioned. The groups that lived northeast of the Illinois apparently were on more familiar terms with the French: Ojibwa ("Sauteur"), Sauk ("Sakis"), Fox ("Outagamis"), Menominee ("Malominis"), Kickapoo ("Kikapous"), Mascouten ("Maidouten," allies of the Kickapoo), Winnebago or Ho-Chunk ("Puants") and Miami (two divisions: "Oumanies" and "Aoniatinonis"). What does the map tell us about the warfare that had just ended? Louis Lahontan, New Voyages to North-America, 1703 (Newberry Library, Graff 2364, v. 1).

Le Cours de Missisipi

The "Grand Nation des Illinois" is shown, as are several villages of or references to sometimes allied peoples: "Pantouatami" (Potawatomi); "Nation du Feu" (Mascouten, allied with the Kickapoo); "Peaugiechio," "Les Checagou" and "Les Miamis" (all Miami-speaking villages). Closer to the Mississippi River are the "Folles Avoines" (Menominee) and the "Renard Nation" (Fox). The "Outaouacs" (Ottawa) are on the southeast shore of Lake Superior. Farther north are "Les Sauteurs" and "Les Missisague" (Ojibwa villages). The map also shows French explorations far to the west, where they met the Dakota ("Issati Orientaux" on the Nadouessioux River). Nicholas de Fer (1646-1720) was a geographer, cartographer, and one of the leading publishers of maps in Paris in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. This map also shows that the French controlled trade in the Ohio, Illinois, and Mississippi River region in 1718. The Iroquois are shown east of Lake Erie. The French still referred to what is now Lake Michigan as "Lac Des Illinois," which reflects the important position of the allied Illinois-speaking villages ("Les Illinois"): Tamaroa, Metchigamias (who seem to have recently moved west). Note the French posts of Fort Louis and Fort Crevecoeur (est. 1679). The Checagou River is named after a village of Miami-speaking people ("Atchatchakangouen"). What most interested the French about this region? Note the detail of the beaver. Note the illustration of men carrying a canoe between waterways (portage). Nicholas de Fer, Le Cours de Missisipi, 1718 (Newberry Library, Ayer 133 .F34 1718).

New Map of the Western Parts of Virginia, Pennyslvania, Maryland, and North Carolina, sheet 1

Hutchins's map was the first large-scale map of the region west of the Allegheny Mountains based on first-hand observations. Hutchins was a captain in the British army. Because the British controlled the region by 1778, the French posts that appeared on the map made by Nicholas de Fer in 1718 are gone. Note the large territory (in green) referred to as "Illinois Country." Several allied villages of Illinois-speaking people are shown on this map. For example, Piorias. Nearer "Lake Michigan" (on earlier maps Lake Ilinese or Illinois) are villages of Miami-speaking people who were allies of the Illinois groups: "Ouiatanon" (Wea) and "Chikago." Note that Indian villages are near the trading posts and routes. Several of the Indian villages in the region were overlooked by Hutchins, which suggests that the British lacked the first-hand knowledge of the French. Can you locate the mines worked by the French and Indians? Can you find the Potawatomi Indians? Thomas Hutchins, New Map of the Western Parts of Virginia, Pennyslvania, Maryland, and North Carolina, 1778 (Newberry Library, oversize Graff 2029, sheet 1).

New Map of the Western Parts of Virginia, Pennyslvania, Maryland, and North Carolina, sheet 2

The map shows "Indiana," which had been sold by the Iroquois, even though they were not living there. Detroit is shown as a multiethnic center. Note the Ottawa and Wyandot villages there. Can you find the large Miami village and the towns of the Delaware and Shawnee? There is a lead mine on the map. Can you find it? Note also that many of the rivers in the region bear the names of Indian groups. Thomas Hutchins, New Map of the Western Parts of Virginia, Pennyslvania, Maryland, and North Carolina, 1778 (Newberry Library, oversize Graff 2029, sheet 2).

New Map of the Western Parts of Virginia, Pennyslvania, Maryland, and North Carolina, sheet 3

Hutchins's map shows how the American colonies already had designs on Indian country. Virginia (marked in blue) claimed the land as far west as the Wabash River in what is now Indiana, even though Indians occupied the region, and Virginia and North Carolina claimed land west to the Mississippi River. Thomas Hutchins, New Map of the Western Parts of Virginia, Pennyslvania, Maryland, and North Carolina, 1778 (Newberry Library, oversize Graff 2029, sheet 3).

New Map of the Western Parts of Virginia, Pennyslvania, Maryland, and North Carolina, sheet 4

Although Virginia claimed land all the way west to the Mississippi River, the map indicates where the "farthest settlement [west]" was in 1755. How does the map reflect the earlier importance of the French in the region? Why does the notation "path to Ottawa country" reflect the importance of the Ottawa in the fur trade? Thomas Hutchins, New Map of the Western Parts of Virginia, Pennyslvania, Maryland, and North Carolina, 1778 (Newberry Library, oversize Graff 2029, sheet 4).

For what did Indians Trade?

Native people developed or borrowed rituals to adjust peacefully to the congregation of different ethnic groups at French trade centers. For example, the calumet ceremony made symbolic kinspeople out of enemies through the transfer of a sacred pipe from one person to another. At the “feast of the dead,” people in several communities brought the remains of their dead to be re-interred in a common grave, and they exchanged gifts, which strengthened the bond between all those in attendance. Another important ritual was the Medicine Lodge, whose leaders obtained help for the faithful from spirit beings and promoted cooperation.

Habit of an Ottawa Indian

The man in the drawing is wearing a loin cloth and robe of European cloth and probably a metal gorget (medal throat or chest cover). His body is adorned by paint or tattoos and he wears trade beads. Indians shaped the trade by demanding the goods that served their interests and appealed to them culturally. Both finished clothing and materials for making clothing (awls, needles) were sought especially by women, and these trade goods reduced women's time and labor in producing clothing for their families. Clothing was as important in trade as metal tools and guns. Photo courtesy of Mackinac State Historic Parks Collection, Michigan.

Paccane, a Miami Man, 1796

Etching done by Elizabeth Simcoe, wife of the lieutenant governor of Upper Canada. This man wears arm bands, a nose ring, and ear wheels-all silver trade goods. He holds a trade tomahawk. His head is shaved except for the scalp lock, which has an ornament attached. Courtesy of Archives of Ontario (F 47-11-1-0-384).

Trade Axe, probably French from the late 1600s

Metal trade axes replaced axes made of stone because they were more durable and more easily acquired. Photo courtesy of Allen County-Ft. Wayne Historical Society.

Silver brooch, Maumee River Valley

This piece was made by Robert Cruickshank (1748-1809). He learned the silversmith trade in London, then came to Boston about 1768. A Tory, during the American Revolution he moved to Canada where he worked as a silversmith in Montreal from about 1781 to 1809. He had a large workshop with several apprentices, where he made domestic silver and large amounts of Indian trade silver. In 1799, he produced over 7,000 items. Women used brooches as fasteners for clothing and as decorations on clothing. They wore large numbers of them on their dresses. Photo courtesy of Allen County-Ft. Wayne Historical Society.

Silver cross, Maumee River Valley

Robert Cruickshank made this engraved piece. Jesuit missionaries routinely distributed crosses, crucifixes, medals, and rings made of several kinds of medal, including silver. These often were engraved with religious symbols, but eventually these items became secular ornaments. Photo courtesy of Allen County-Ft. Wayne Historical Society.

Engraved Silver bracelet or Arm Band

This was made by Pierre Huguet dit Latour (1749-1817), of Montreal. He worked in Montreal from about 1780 to 1816, producing large quantities of trade silver. This piece was found in the Maumee River Valley. Bracelets, arm bands, and leg bands were popular. Traders distributed metallic ornaments as condolence gifts at mortuary rituals and Indians used these ornaments as grave offerings. Photo Courtesy of Allen County-Ft. Wayne Historical Society.

Silver Gorget

Robert Cruickshank made this circular gorget or breast plate. The gorget has two studs at the upper curve for securing loops on the back of the piece. European officials gave gorgets and medals to important leaders in order to keep their allegiance. These objects had high prestige value and aspiring leaders sought them. The likeness of the coat of arms of a monarch might be engraved on gorgets or medals. Europeans also wore gorgets. Originally they were part of plate-armor worn by nobility. After armor no longer was worn, the gorget was retained as a symbol of rank. Photo courtesy of Allen County-Ft. Wayne Historical Society.

Copper pot

This pot was found near Miami Town and was used from the 1780s to about 1810. Copper pots replaced pottery and other containers because the metal pots were more durable and easily replaced. Photo courtesy of Allen County-Ft. Wayne Historical Society.

Copper pot, Hudson Bay Style, 18th Century

This pot is possibly from the Maumee River Valley area. When a pot was no longer needed, the metal would be reused to make tools and weapons. Photo courtesy of Allen County-Ft. Wayne Historical Society.

Necklace, Made of Glass, Stone, and Shells

It was found near Miami Town. Such a necklace was a valued trade item, probably made by an Indian craft worker using trade beads. Photo courtesy of Allen County-Ft. Wayne Historical Society.

Listen to one of the ojibwa accounts of the origin of the medicine lodge

Midewewin Lodge. Video courtesy of WDSE-Duluth/Superior, MN. View transcriptThe fur trade also resulted in an intensification of warfare among Native peoples, who competed for access to the French. East of Lake Huron, Iroquois people obtained guns and began to expand west, making war on the peoples trading with the French in order to gain control of the trade themselves.

During the Beaver Wars of the 1630s through the 1650s, the Iroquois displaced the Wyandot, forcing their dramatically reduced population westward. The French established Montreal in 1642, and by the 1680s the Ottawa, who lived west of the Wyandot, assumed the middleman role. Ojibwa contacts with French traders and their acquisition of the gun led to their expansion south into Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan. In present-day Minnesota they came into contact with the numerous Dakota, who tried to hold their territory. The entire Great Lakes region was a war zone in the 17th century. In 1701 peace was negotiated with the Iroquois.

In the mid-18th century, Native peoples were living peacefully in a multiethnic region where Indians, Europeans, and mixed ancestry (Métis) people all contributed to the regional economy and cooperated. But ultimately the French and English empires drew Indians into their quarrel over who would control the Great Lakes region. War erupted in 1754 in Ohio. The conflict resulted in warfare among Indians, population dislocation, and numerous villages of refugees. Alliance with the French was attractive because they did not want to settle on Indian lands and they behaved as generous kinspeople. The British won some support by offering to stem the tide of trespassing colonists crossing westward beyond the Appalachian Mountains. But after Britain prevailed over France in 1763, Indian leaders saw with dismay that the trespasses continued. In 1763 the Ottawa warrior Pontiac led a short-lived regional, multi-tribal independence movement, supported by a new religion that drew on spirit beings for help.

Do you want to learn more about warfare?

Attack on Fort Michilimackinac by Pontiac's Followers

Pontiac was born in 1720 in a village near what is now Detroit. He grew up in a multiethnic community. His father was Ottawa and his mother was Miami or Ojibwa. His village was loyal to the French during the French and Indian War. By 1762, Pontiac had an outstanding reputation as a warrior and he was an eloquent speaker. Pontiac's village found British administration onerous. He formed an association with Neolin, a Delaware prophet, who was preaching that messages from spirit beings mandated a return to "traditional ways" and a rejection of British trade goods. With the backing of the prophet and promises of help from the French, Pontiac met with warriors from villages throughout the Great Lakes area and then launched an attack on British forts in 1763. He led followers in an attack on Fort Detroit in May. Elsewhere, his followers attacked forts in Ohio, Michigan, and Indiana. Ojibwa and Sauk made the attack on Fort Michilimackinac. As illustrated in the drawing, they pretended to play ball and when the ball went into the fort they continued the game there. They attacked once inside the fort, taking the British by surprise. Pontiac's followers captured 8 of 12 forts and forced the abandonment of a ninth. But the French made peace with the English and withdrew their help. Pontiac subsequently lost stature among his followers. He left the Michigan and Ohio area and went west among the Illinois, where he was assassinated in 1769. Raymond McCoy, The Massacre of Old Fort Mackinac (Newberry Library, Ayer 150.5 .M57 M13 1940).

Wingenund's War Record

Indian men kept bark pictographic records of their war experiences. Wingenund was a Delaware war leader who joined Pontiac in the 1763 rebellion against the British. Seth Eastman's drawing shows the symbol of Delaware ethnic identity (the turtle), a symbol for Wingenund's spirit helper (#2), the sun (#3), and (on the right) 10 horizontal lines representing ten war parties. On the left are his accomplishments during each war party. These stick figures show men and women killed or taken prisoner. He participated in the capture of a fort on Lake Erie (#8), the siege of Detroit (#9), the attack on Fort Pitt (#10), and an attack on a town near Detroit (#11). Drawing by Seth Eastman in Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, Historical and Statistical Information, Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States (Newberry Library, Ayer 250 .S3h 1851, v. 1, pl. 47, fig. B).

The Figured Stone or Shing-Gaa-Ba-Wosin

This portrait was painted by James Lewis in 1826 at the Treaty of Fond du Lac when The Figured (or Image) Stone was 82. He was a distinguished Ojibwa warrior who attended treaty councils in his old age. He received a presidential medal (a medal with the president's image on it) for his treaty council participation. He lived at Sault Ste. Marie but spent much of the time hunting and fishing west of Lake Superior. He died in 1828. Drawing by Seth Eastman in James Otto Lewis, North American Aboriginal Port-folio (Newberry Library, Ayer 250.6 .L67 1838, no. 1).

Grave post of Shing-Gaa-Ba-Wosin or The Image Stone

On his carved post is his family [clan] symbol, the Crane-here upside down to indicate death. On the right are 6 horizontal "marks of honor" that indicate battles in which he distinguished himself, including those he fought as part of Tecumseh's warriors. On the left, the three horizontal bars represent three treaty councils in which he participated as an Ojibwa spokesman. He was opposed to land cessions but by the 1820s had realized that military resistance was futile. Drawing by Seth Eastman in Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, Historical and Statistical Information, Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States (Newberry Library, Ayer 250 .S3h 1851, v. 1, pl. 50, no. 4).

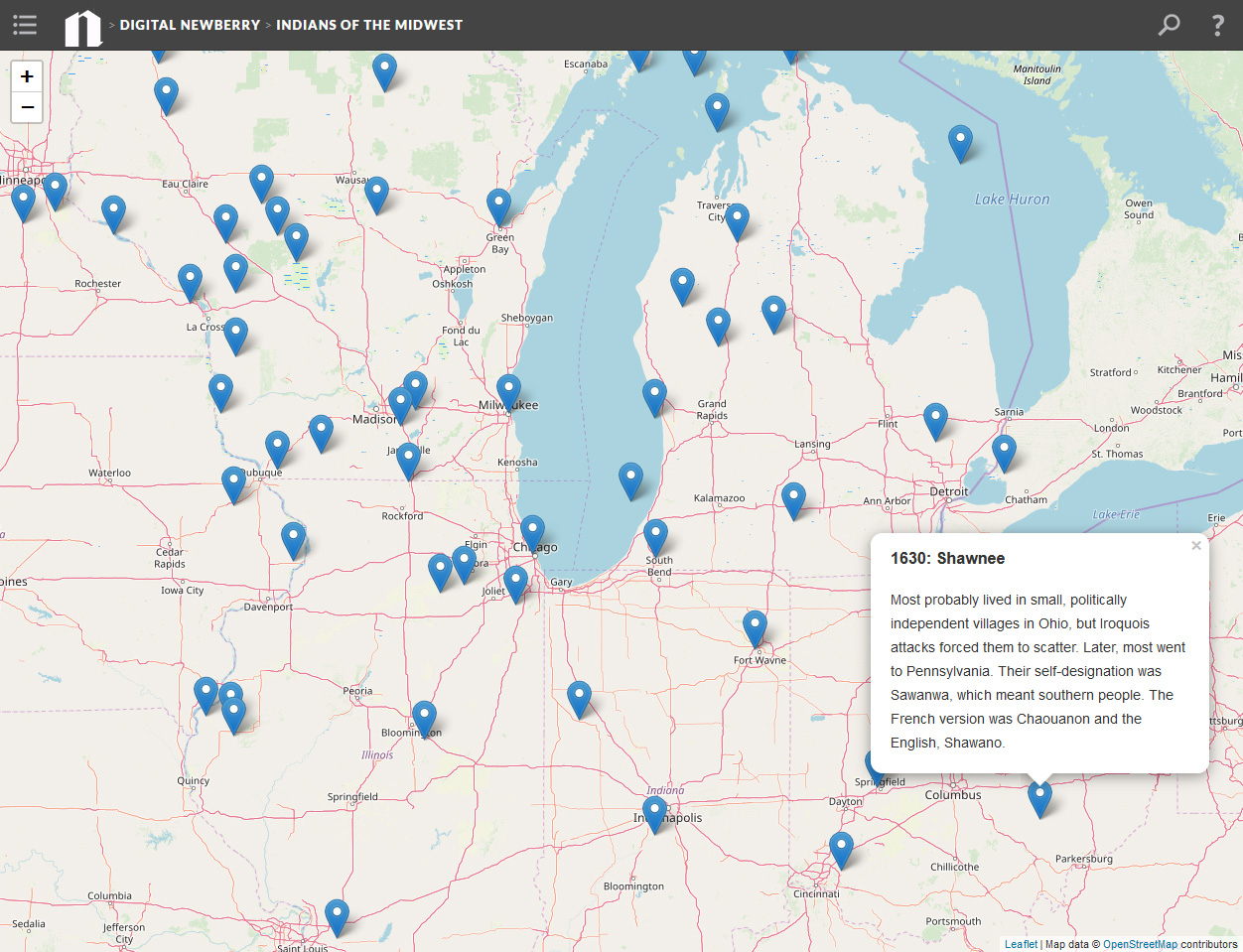

Interactive map: Explore trading post locations

Jolliet and Marquette Visit the Great Village of the Illinois

In the summer of 1673, a French expedition led by Louis Jolliet, a young French Canadian fur trader, and a Jesuit priest, Jacques Marquette, reached two villages of Illinois-speaking Indians. This expedition by seven men in two birchbark canoes descended the Mississippi River to the mouth of the Arkansas River, then returned to the Great Lakes by way of the Illinois River. They visited a Peoria village near the Mississippi River and a Kaskaskia village on Illinois River in north-central Illinois. Note that Marquette is offering a calumet. Their report was the earliest first-hand account of the Illinois Indians. The voyage of Jolliet and Marquette paved the way for French expansion into Illinois country. Robert A. Thom painting, 1967, imagined from documentary sources, but the calumet was presented by the Illinois to the two Frenchmen, not by Jolliet to the Illinois. When Marquette and Jolliet left the Illinois village, they were given a calumet to see them safely through the territory of other groups. Reproduction courtesy of the Illinois State Historical Society.

White Trader with Ojibwa Trappers, ca. 1820

This painting shows a trader meeting with an Ojibwa winter hunting party with furs to trade. The Ojibwas are wearing wool garments and carrying guns and metal knives—all products of European manufacture. Note also that items made by Ojibwas still are in use, such as fiber bags and snowshoes. This is a watercolor, gouache over pencil; artist anonymous. Courtesy of Royal Ontario Museum.

Meda Scroll, Medicine Lodge

The pictographs on the board symbolized spirit encounters. They served as mnemonic devices for rituals and songs of the Medicine Lodge, a new religion that emerged in the 17th century. It essentially was a society of people who had acquired through apprenticeship the knowledge to cure illness. The leaders (Meda) helped followers maintain good health—more difficult after Europeans brought new diseases for which Indians had no immunity. The leaders also used their influence to persuade people to cooperate with political leaders who were working to develop partnerships and alliances between villages. The Medicine Lodge religion was embraced by all the Native groups in the region. Drawing by Seth Eastman in Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, Historical and Statistical Information, Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States (Newberry Library, Ayer 250 .S3h 1851, v. 1, pl. 51).

Ojibwa-Fox Battle

The Ojibwa and the Fox competed for access to French trade goods. This drawing by Seth Eastman illustrates events that followed a Fox raid on the Ojibwas at La Pointe. The Ojibwa pursued the Fox across Lake Superior, and they fought from their canoes. The former greatly outnumbered the Fox and defeated them. Eventually the Ojibwa forced the Fox from the area, probably in the early 17th century. Drawing by Seth Eastman in Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, Historical and Statistical Information, Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States (Newberry Library, Ayer 250 .S3h 1851, v. 2, pl. 32).

Iroquois Wars, 1641-1701

During the Beaver Wars (1630s-50s), the Iroquois attacked into the Ohio River valley, eventually driving the Algonkian-speaking groups living there out of present-day Ohio and Michigan. In Wisconsin and Minnesota the survivors of Iroquois raids congregated in contiguous villages or in multiethnic villages, often near a French post, to try to defend themselves with help from the French. Note that the Iroquois reached the country of the Illinois-speaking villages and fought major battles there (X). Forts are indicated by squares and Indian villages by triangles. Ethnic group abbreviations: IL (Illinois); OT (Ottawa); TI (Tionontati, refugees and allies of Hurons); SH (Shawnee); MI (Miami); MES (Fox); MC (Mascouten); PO (Potawatomi); KI (Kickapoo); SA (Sauk); WI (Winnebago); OJ (Ojibwa); ME (Menominee); HU (Huron). Detail from Map 6 in Helen Hornbeck Tanner, ed., Atlas of Great Lakes Indian History (Newberry Library, Ayer folio E78.G7 A87 1987).

Susan Johnston (Oshawguscodaywayqua)

Susan Johnston (Oshawguscodaywayqua) was born in 1772, the daughter of Waubojig, an important Ojibwa chief from La Pointe,Wisconsin. She married John Johnston, an Irishman who was a trader among the Ojibwa for forty years. James Lewis painted her portrait in 1826. She wore a cloth petticoat and gown, and beaded leggings and moccasins. She knew Ojibwa leaders and European traders and was a respected and influential person in her region in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. She had seven children, and one daughter married the Indian agent Henry Schoolcraft. Mrs. Johnston was one of many women married to Europeans and Americans who contributed to the success of multiethnic, multi-racial relationships. Her children were part of the Métis community. Thomas Loraine McKenney, Sketches of a Tour to the Lakes (Newberry Library, Ayer 128.7 .M25 1827).

Frederick Faribault, Métis

Faribault’s family was in the Indian trade. His father, Jean Baptiste, was a French-Canadian trader who worked out of Prairie du Chien. Jean Baptiste Faribault married Pelagie, a Métis woman whose mother was Dakota. The family was “Creole,” that is, their way of life was a blend of Indian and Euro-American custom. For example, Creole communities practiced both European methods of farming and worked in the fur trade. Frederick was about 25 when Frank Blackwell Mayer sketched him in 1851. Drawing by Frank Blackwell Mayer in Frank B. Mayer collection of sketchbooks, drawings, and oil paintings of Sioux Indians during the 1851 treaty negotiations at Traverse des Sioux and Mendota, Minn. (Newberry Library, oversize Ayer Art Mayer, sketchbook #42, p. 102).

-

1

2021-04-19T17:20:00+00:00

How We Know

1

plain

2021-04-19T17:20:00+00:00

Why do non-Indian Americans think about Indians the way they do, and what are the consequences? Scholars have explored these questions by analyzing the images of “Indianness” used by Americans. From colonial times forward, “Indian” figures or characters appeared in visual form–paintings, photographs, cartoons, home furniture and accessories, pageants and public shows, advertisements, film, and logos. Portrayals of “Indians” also occurred in songs, jokes, and games. Indian imagery has two themes: ignoble and noble qualities. Scholars argue that such imagery served and serves a purpose—to reconcile the contradiction between the ideals of national honor and the actual treatment of Indians in America. As this viewpoint gained wide acceptance in the 1970s, anthropologists, historians, and other scholars worked to expunge biases and incorporate Native perspectives into their work.

Americans’ ideas about Indians were shaped by their colonial history. Beginning with Columbus, Indians were represented as either “noble” (healthy, free, guileless, in harmony with nature, exotic, cooperative, and uncorrupted by “civilized” institutions such as government or religion) or “ignoble” (ferocious, warlike, wild, degraded). Europeans sent missionaries to convert and officials to negotiate for land purchase or trade with the “willing” noble savage. Any resistance to European terms by ignoble savages became “just cause” for military subjugation.

During the Revolutionary War and for generations after, Americans relied on Noble Savage imagery to help establish a national identity and to justify making treaties with Indians. Ignoble Savage imagery rationalized war and dispossession through violence.

Americans who protested against British rule commonly dressed as Noble “Indians,” who represented freedom and an ancient association with North America, rather than with Europe. Men’s organizations took on this Indian theme in subsequent years as an expression of American patriotism.

Treaties (from 1785 to the 1820s in the Midwest) were represented as “expansion with honor” because Indians ostensibly gave their consent to land cessions in return for assistance to survive as communities. Imagery of treaty councils portrayed Indians as willing subordinates.

On the other hand, frontiersmen opposed the treaty policy and trespassed and committed hostile acts in Indian country. Indians retaliated as they tried to defend their homeland, which led to war against Indians in the Midwest in 1790-95. Imagery of Indians as violent and bestial both reflected and reinforced frontier sentiments.

By the 1820s, the federal government began to promote a new solution to the problem of how to transfer Indian land to U. S. citizens, the “Removal Policy.” Officials vigorously pursued this effort to move Indians west of the Mississippi River during the 1830s and 1840s, effectively disregarding the treaties that had guaranteed land to Indians in their homeland. The “republicanism” of the Constitution (which gave control of the government to men who owned property) gave way to the new ideal of “democracy,” ostensibly based on majority rule, free enterprise, minimal government that benefited all alike, and individual opportunity. Without land ownership, social mobility was unlikely, so the proponents of democracy were settlers in the frontier region and other landless Americans, who supported Indian removal.

The national narrative was that Indians, regarded as inferior to White people, were doomed to extinction. Removal treaties, that provided land and assistance to help Native people survive elsewhere, would be their only salvation. The federal government would offer Indians (declared “wards” of the government by the Supreme Court) protection and assistance. Indian imagery both reflected these views and promoted them. “Noble” Indians were portrayed as doomed or pitiful, not capable of being part of American society. Indians who resisted removal were portrayed as obstacles to progress in the ignoble savage tradition, which rationalized war against them.

After the removal of most of the Native peoples in the Midwest area (and the military defeat of tribes west of the Mississippi River), the federal government devoted more resources to the “civilization” program and ended treaty-making with tribes. Those tribes on reservations saw their land divided into individually-owned plots and the remainder sold. Federal agents on the reservations had the power to deny their wards freedom of religion, parental rights, and self-government, and they controlled tribal and individuals’ property. Non-Indians were able to obtain Indian land and resources (such as timber) very cheaply, because the prevailing policy was that non-Indians would make better use of them. The rationale for this kind of treatment was that Indians would benefit from civilization. When, instead, poverty and graft resulted from reservation life, Indians were blamed as deficient.

The Noble Indian imagery, in which Indians were associated with a past Golden Age, remained popular in the late 19th and 20th centuries. Americans were nostalgic about Indians in the past. They could draw on this imagery to sell products and develop tourism. Indian imagery also was used to create personal or group identities (for example, as Boy Scouts, countercultural activists, or sports fans). By their preoccupation with Indians of the past, Americans could ignore the circumstances of contemporary Indian life.

How did Americans represent “noble” Indians in the Great Lakes region and why was this imagery popular?

Perfume Advertisement, 1885

The woman on this trade card for Indian Queen Perfume (Bear and Brother Co.) is demure, exotic, and elegantly dressed—the image of the Indian Princess. The Princess is the female version of the Noble Indian; the "Squaw" is the Bad Indian. In the forest, this princess figure extracts the essence from the flower for the benefit of the customer. Indians were a common source of imagery in advertising, especially for patent medicines, which were marketed as Indian potions. Indians of the past were seen as having a unique communion with nature and its curative powers. By the late 1880s, Native people no longer were a threat to Americans, and, in fact, were often socially invisible. So in the advertisements they appear romanticized and exotic. These kinds of ads that depict minorities in caricatures created a sense of middle class consumer solidarity that helped sales. Photo by Brian Mornar, courtesy of Newberry Library.

Land O Lakes

The Indian maiden on the carton is shown as part of nature and dressed in what the artist imagined as 19th century clothing. She is a "princess" character, helpful to Americans, in this case offering them a healthful product associated with the Great Lakes region. Photo courtesy of Brian Mornar.

Winnebago Indians at Stand Rock, postcard, ca. 1913

These Ho-Chunks are at the landing of the steamboat "Winnebago." They were performing at Stand Rock Amphitheater for an audience of tourists. This postcard helped attract tourists and shaped what they thought about Indians. "Real" Indians were associated with "long ago and far away," dressed in 19th century Plains clothing, and dancing. These Ho-Chunks actually were entrepreneurs working as professional entertainers. Other kinds of jobs were difficult for them to get, but jobs as entertainers served the interests of the tourist industry in Wisconsin. Photo by H. H. Bennett Studio, courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society (34535).

Highway Map, Minnesota, 1924

This road map was available to tourists and was intended to encourage travel by auto up into the recreational regions of the state. The modern buildings and cars and attractive, modern housing take center stage. The "Indian" is in the wilderness, partially clothed and barefoot, seemingly estranged from modern Minnesota. On the other hand, he projects an exotic image that promotes tourism in the state at a time when Indian performers were working in the state parks and elsewhere. (Newberry Library, Road Map4C G4141.P2 1924 .R3).

Playing Indian

This commercial photo was staged and taken by H. H. Bennett, ca. 1905. He entitled it "Boat Cave." In the photo, three White men impersonate Indians spearing fish, hunting with a bow and arrow, and paddling a canoe in a dark (and dangerous?) cavern. They wear chicken-feather headdresses and drape themselves in blankets. The men are enacting scenes from an imagined Ho-Chunk past. Americans imitated certain features of imagined Indian life in all sorts of situations in order to construct individual or collective identities. The men in the boat are affirming their identity as outdoorsmen, brave and athletic. Bennett does not report what they did in their everyday lives. Photo by H. H. Bennett, ca. 1905, modern print from an original stereographic glass negative, courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society (7264).

Read one scholar’s analysis of “The Song of Hiawatha” (1855), which became America’s best known narrative poem and helped to shape national identity

Alan Trachtenberg explores the role of “The Song of Hiawatha” in American life. The poem was written by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, whose chief source was the work of Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, who published Ojibwa stories about a supernatural being who both helped and harmed humans. Longfellow renamed him Hiawatha, after a heroic Iroquois figure. Longfellow’s poem became a folk tradition for Americans, and “Hiawatha,” the “good Indian,” appeared in coloring books, songs, performances, visual art, and other contexts. In discussing the end of the poem, when Hiawatha departs his homeland, Trachtenberg writes:

Longfellow contrived “a ‘departure’ scene, an Indian ‘assumption’ of a dead or dying god figure redeeming a nation that had in real life spilled oceans of blood and inflicted immeasurable bodily pain to achieve its dominance . . . . Repeated performance of gentle Hiawatha’s farewell passion displaced and substituted for a history of actual blood sacrifice . . . and it gave the nation an aestheticized version of its own unspoken historical memory.” From Alan Trachtenberg, Shades of Hiawatha, 2004, pp. 87-88Read these stanzas from the end of The Song of Hiawatha [1855], 1911 by Longfellow. Can you find the imagery which Trachtenberg uses to convey these themes: Hiawatha’s nobility and welcoming of the White man. His willing departure in the face of a superior way of life that became available to his people. What emotion is evoked by these images? “sun descending,” “clouds on fire,” and “westward Hiawatha sailed into the fiery sunset, the purple vapors, the dusk of evening”?

And the noble Hiawatha,

With his hands aloft extended,

Held aloft in sign of welcome.

Waited, full of exultation,

Till the birch canoe with paddles

Grated on the shining pebbles,

Stranded on the sandy margin,

Till the Black-Robe chief, the Pale-face,

With the cross upon his bosom,

Landed on the sandy margin.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Forth into the village went he,

Bade farewell to all the warriors,

Bade farewell to all the young men,

Spake persuading, spake in this wise:

“I am going, O my people,

On a long and distant journey;

Many moons and many winters

Will have come, and will have vanished,

Ere I come again to see you.

But my guests I leave behind me;

Listen to their words of wisdom,

Listen to the truth they tell you,

For the Master of Life has sent them

From the land of light and morning!”. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

And the evening sun descending

Set the clouds on fire with redness,

Burned the broad sky, like a prairie,

Left upon the level water

One long track and trail of splendor,

Down whose stream, as down a river,

Westward, westward Hiawatha

Sailed into the fiery sunset,

Sailed into the purple vapors,

Sailed into the dusk of evening.

(pages 219-20, 224-25)The image of the ignoble Indian survived into the 20th century, as well. In contrast to Indians in the past, Indian contemporaries were no longer “noble” but, rather, degraded (lazy, corrupted, even “fake”), particularly when they challenged the status quo.

What scholars argue is that Indians have been and are treated as alien to American society, on the one hand, and a necessary part of national identity, on the other. Indian imagery, as used by Americans works to reconcile the tension between American ideals and the harsh reality of Indians’ treatment.

Listen to historian Dave Edmunds explain how imagery associated with Tecumseh changed over time to accommodate American interests

Dave Edmunds on Tecumseh imagery. Production by Mike Media Group, 2009. View transcript | View at Internet ArchiveAcademic publications, as well as textbooks and films, have promoted this Noble/Ignoble Indian imagery. In recent years, scholars have recognized the distortions inherent in this kind of Indian imagery and committed to acknowledging or incorporating Native interpretations, viewpoints, and explanations into their work. In this spirit, Native American studies programs have been established at major universities in the Midwest region.

Listen to ethnohistorian Ray Demallie explain how the writings of Charles Eastman helped him gain a better understanding of Dakota culture and history

Raymond DeMallie on Charles Alexander Eastman's writings. Production by Mike Media Group, 2010. View transcript | View at Internet ArchiveMuseum professionals also have committed to acknowledging the importance of Native participation.

Listen to anthropologist Nancy Lurie explain how the Milwaukee Indian community took a major role in planning a new exhibit area at the Milwaukee Public Museum

Nancy Oestreich Lurie on planning a new exhibit at the Milwaukee Public Museum. Production by Mike Media Group, 2010. View transcript | View at Internet ArchiveThe powwow exhibit at the Milwaukee Public Museum not only was planned by local Indian people, but they also posed for the facial casts of the dancers and made the dance outfits.

Would you like to hear more about the powwow exhibit?

Nancy Oestreich Lurie on the powwow exhibit at the Milwaukee Public Museum. Production by Mike Media Group, 2010. View transcript | View at Internet ArchiveMémoires, 1705

This is an illustration from Mémoires de l’Amérique septentrionale, a narrative by Louis Armand de Lom d’Arce, Baron de Lahontan, a French officer who interacted with the Indians in Canada, including Ojibwas and Ottawas. This detail, “Sauvages of Canada” shows, left to right: a man going to the hunt, an elderly man walking through the village, a young man walking. The female carries an infant. The Indians are drawn in a classical European style. Instead of portraying male warriors, the Indians represented are male and female, old and young. Lahontan shows the Indians, who the French want to convert to Christianity, as noble savages receptive to missionary work. This noble imagery is intended to generate support for missionaries. Louis Lahontan, Voyages du baron de la Hontan, dans l’Amérique septentrionale (Newberry Library, Ayer 123 .L16 1705, v. 2, pg. 94-95).

Habit of an Ottawa Indian

The man’s classical stance and exotic look are typical of representations of “noble savages” in the early 18th century. The man is drawn wearing many items of European manufacture: cloth, metal gorget, beads. The image suggests that he is an eager trading partner; thus, he is portrayed as noble. Photo courtesy of Mackinac State Parks Collection, Michigan.

The Tea-Tax-Tempest, 1778

This engraving by Carl Gottleib Guttenberg (1743-90) was entitled, “The Tea-Tax-Tempest, or the Anglo-American Revolution.” Here, Guttenberg represents a satirical view of the Boston Tea Party. The character “Time” uses a magic lantern to show on a curtain an allegorical representation of the Revolution. Watching are four female figures that represent the four continents: America (partially clothed with bow and arrow and feathered headdress), Africa, Asia (holding a lantern), and Europe (with shield). Stamps are burning in the teapot on the fire. A cock (the emblem of France) blows on the fire with a bellows. The torn flag with three leopards represents Britain. On the right American soldiers advance, led by an allegorical figure of an Indian woman, partially clothed and wearing a feathered headdress, who reaches for the cap and staff of liberty. On the left, British soldiers flee. The artist associates the nationalist, protest movement of the American colonists with Indian imagery, a common perspective in Europe. Guttenberg was born and trained in Germany and lived in Paris. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photograph Division (LC-USZC4-4601).

Order of Red Men Certificate

This is the 1889 membership certificate of the “Improved Order of Red Men” (the reorganized Society of Red Men, established in 1816 shortly after the War of 1812). The Society of Red Men, initially founded by veterans, was focused on associating the “Indian” with anti-British sentiment, and it offered aid to its members and their families. They considered themselves an elite but felt anxious about social change. They associated their group with the ancient wisdom of the aborigines. The images on the certificate represent Indians in the past, engaged in hunting, warfare, religious ceremonies, and treaties. The Improved Order of Red Men was organized in 1834. This men’s organization had regalia, names, and rituals modeled after Indians. The membership was divided into “tribes,” and there were many such groups in Ohio and Indiana. By 1935 there were 500,000 members; today, about 38,000. They consider themselves descended from the Sons of Liberty, who participated in the Boston Tea Party and other protests against the British, dressed as “Indians.” In fact, the independence movement made considerable use of flags and handbills with Indian imagery. Certificate designed by P. Gorham and P. Hollis, photo courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division (pga.03413).

William Penn’s Treaty with the Indians, 1771

This oil painting by Benjamin West (1738-1820) represents Penn’s meeting with the Delaware in 1682 and portrays Penn and the colonists as proponents of peace. The Indian figures seem eager to exchange bales of cloth for land. In the background are “civilization” images (ships and houses under construction in the forest), which contrast with the “primitive” Indian people and imply that the colonists are bringing a better life to the Indians. This painting actually is a representation of treaties in general, not the 1682 council. The idyllic setting and subservient poses of the Indians suggest that Indians ceded land willingly. Actually, the colonists pursued war to expel Indians from their lands. West’s painting rationalizes the land loss as something positive for the willing and “noble,” but inferior, Indians. Painting by Benjamin West, courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, gift of Mrs. Sarah Harrison (The Joseph Harrison, Jr. Collection), pafa.org.

Andrew Jackson, the Great Father, engraving, ca. 1830

President Jackson is portrayed as a protector of vulnerable, needy, and subservient Indians, who appear childlike (or even like dolls, that can be manipulated). Jackson, representing the federal government is shown as a father figure. Actually, Jackson used executive power to force Indian removal. At this time, when Indians in Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois were being removed from their homelands despite promises made by the U. S. in earlier treaty councils, portraying the president’s removal policy as beneficent toward Indians rationalizes a policy that resulted in severe hardship and population loss for Indians. Drawing courtesy of University of Michigan, Clements Library.

General Harrison and Tecumseh, lithograph, 1860

This scene represents a meeting between Tecumseh and William Henry Harrison at Vincennes in August 1810. Tecumseh is portrayed as a large, muscular, threatening Indian who reacted to Harrison with violence without provocation. This image of Tecumseh helped to justify the violence against and the removal of Native people from the Ohio Valley. If they were so uncivilized as to be unable to negotiate, then their extinction was unavoidable. This illustration was based on a drawing by Chapin and W. Ridgway, published by Virtue & Co. in 1860. Drawing courtesy of Indiana Historical Society (P483)

Move On, 1894

Illustration from History of the United States. In Bill Nye’s text, this illustration by F. Opper is entitled “Move On, Maroon Brother, Move On!” The negative image of a ragged, caricatured Indian being pushed off a cliff by a robust character (“Civilization”) under a setting sun gives expression to the sentiments of proponents of westward expansion. The Indian is vilified in order to rationalize the removal of Indians from their homes. The passage in the text being illustrated argues that Indians are not “noble”: “the real Indian . . . he lies, he steals, he assassinates, he mutilates, he tortures.” Drawing by F. Opper in Bill Nye, History of the United States (Newberry Library, F 83 .64, p. 317).

The Departure of Hiawatha, 1868

The artist Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) was a prominent American painter of landscapes who trained in Europe. This small 7 X 8 inch oil on paper work was presented by Bierstadt to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow as a gift. The painting evokes strong emotion. The imposing sunset suggests that the Indian way of life is over, but the sunset is not gloomy; rather, the color and light produce an almost religious aura. The small Indian figures seem part of or encompassed by nature. Hiawatha represents the heroic Indian of the past. The disappearance of Indians, the painting suggests, was inevitable and complete. This powerful image of Indians belonging to the past, not the present, made it easy for Americans to ignore Indian issues in contemporary times. Courtesy of National Park Service, Longfellow House—Washington’s Headquarters National Historic Site.

Lo, the Poor Indian, 1875

This lithograph by Vance, Parsloe and Co. ridicules the Indian of the time. He is shown drunk, with torn, mixed White and Indian style clothing. His face has a foolish countenance. He carries useless “tools”: a rifle, hatchet, and knife. The phrase at the bottom, “Oh why does the White man follow my path!” possibly mocks the “noble savage” imagery that also was being used in the late 19th century. This rendering works to rationalize the federal government’s breach of treaty agreements and the fraudulent management of Indian property and funds that characterized these times. The phrase “Lo, the poor Indian,” is from Alexander Pope’s 18th century “An Essay on Man”: “Lo, the poor Indian whose untutor’d mind Sees God in clouds, or hears him in the wind.” Pope’s imagery illustrates the noble savage theme. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Publications Division (LC-USZ62- 92901).

Political Cartoon, 1888

This cartoon, a reproduction of a drawing by Edward Windsor Kemble, is entitled “Aboriginal Susceptibility.” It is a caricature of two “agency” Indians. The men are given ridiculous “Indian” names. Man With Frayed Ear asks, “What for you cry?” Man Afraid of Red Headed Horse replies, “Injun think what dam shame he’s Injun.” The appearance of the men and the non-standard dialect of English (a stereotype in itself) rationalize and make fun of Indian poverty, suggesting that Indians themselves are to blame. One Indian man wears a blanket marked U. S. property, suggesting dependence. The men are overweight with darkened and big-nosed faces, suggesting corruption. In the background are a well-dressed woman and a soldier conversing, oblivious to the Indians, with good reason, it appears. This cartoon was published in Puck’s Library, in an issue devoted to “out West” themes that made fun of Indians. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division (LC-USZ62-55997).

Family Circus Cartoon, April 20, 2002

The boy playing “Indian” links his identity to a casino and, wearing a tuxedo, sends a message that he is wealthy. The cartoon suggests that Indians are not “real” if they own a profit-making business—in fact, they appear ridiculous. The boy in the tuxedo also conveys the idea that casinos have made Indians rich from unearned income. To modern Americans, “real” Indians are not competent business owners who are successful. That situation conflicts with the common stereotype of Indian poverty and dependence. So Indians who own casinos must be somehow “fake.” Actually, tribes, not individuals, own casinos and the profits are put into community development projects. But the hostility toward Indian casinos also reflects resentment toward Indian competition with other gaming interests and a general resentment of attempts to change the status quo. The ridiculing of Indian gaming and other forms of backlash make it more difficult for tribal businesses to succeed. Family Circus ©2002, Bil Keane, Inc., King Features Syndicate.

Do you want to do your own research on Indian Imagery?