Grave post of Shing-Gaa-Ba-Wosin or The Image Stone

1 2021-04-19T17:19:59+00:00 Newberry DIS 09980eb76a145ec4f3814f3b9fb45f381b3d1f02 8 1 Grave post of Shing-Gaa-Ba-Wosin or The Image Stone. Drawing by Seth Eastman in Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, Historical and Statistical Information, Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States (Newberry Library, Ayer 250 .S3h 1851, v. 1, pl. 50, no. 4). View catalog record plain 2021-04-19T17:19:59+00:00 Newberry DIS 09980eb76a145ec4f3814f3b9fb45f381b3d1f02This page is referenced by:

-

1

2021-04-19T17:19:58+00:00

Fur Trade

1

image_header

2021-04-19T17:19:58+00:00

Above: A general map of New France commonly call'd Canada. Louis Lahontan, New Voyages to North-America, 1703 (Newberry Library, Graff 2364, v. 1). View catalog record

In the early 17th century, French traders began to use Huron (or Wyandot) middlemen to trade with the Native peoples in the Great Lakes region. Native people belonged to several “ethnic” groups. The members of an ethnic group (for example Ojibwa or Menominee) spoke the same language and shared a common history and identity, but did not all live in the same community or recognize the same leaders.

What did European mapmakers know?

The French came for furs, especially beaver pelts used to make felt hats. The French succeeded because they adopted the technology and accepted the social customs of Native people. These Frenchmen traveled by birchbark canoes along old trade routes, using Indian guides and interpreters, learning Indian names for rivers and villages, and surviving on Indian corn. They established trade relationships with villages by participating in well-established rituals. They were adopted as kinsmen by a village leader in the calumet ceremony.

They also married Native women and became in-laws. They brought gifts to important people when there was a death. Gift-giving helped maintain the alliances between French traders and Native leaders. Native people eagerly sought the European trade goods because these items often worked better, lasted longer, and saved labor. Indian villages relied on the few French posts in the region or dealt with independent traders who reached their villages.

New Voyages to North-America, Mackinac Region

This map shows a settlement of French, Huron, and Ottawa on the south shore of Lake Huron. Note the importance that fishing for whitefish receives. Jesuit missionaries (B) accompanied the French traders everywhere. The Huron village (C) and Ottawa village (E) not only depended on trade in furs. They grew crops for themselves and for the French (D). Louis Armand, Baron de Lahontan (1666-1715), was in the French military in New France and traveled throughout the Great Lakes area. His geographical errors (for example, the "Long River") influenced cartography for 100 years until the Lewis and Clark discoveries. Louis Lahontan, New Voyages to North-America, 1703 (Newberry Library, Graff 2364, v. 1).

New Voyages to North-America, General Map of New France

This map shows where French traders were established by the end of the 18th century. Montreal was a major trade depot, and note LaSalle's fort on the southeast shore of Illinois Lake and Fort Crevecoeur, established by La Salle in 1679, on the Ilinese [Illinois] River. The British presence is farther east. The dispersal of the Huron is reflected on the map, as well as the important middleman role of the Ottawa (Outaouas). Note the major waterway named after the Ottawa. The Illinois-speaking groups were very powerful at this time-note that what is now Lake Michigan is "Ilinese" [Illinois] on the map. But the map has little detail on the numerous Illinois villages-only "Ilinese" and "Tamaroa" are mentioned. The groups that lived northeast of the Illinois apparently were on more familiar terms with the French: Ojibwa ("Sauteur"), Sauk ("Sakis"), Fox ("Outagamis"), Menominee ("Malominis"), Kickapoo ("Kikapous"), Mascouten ("Maidouten," allies of the Kickapoo), Winnebago or Ho-Chunk ("Puants") and Miami (two divisions: "Oumanies" and "Aoniatinonis"). What does the map tell us about the warfare that had just ended? Louis Lahontan, New Voyages to North-America, 1703 (Newberry Library, Graff 2364, v. 1).

Le Cours de Missisipi

The "Grand Nation des Illinois" is shown, as are several villages of or references to sometimes allied peoples: "Pantouatami" (Potawatomi); "Nation du Feu" (Mascouten, allied with the Kickapoo); "Peaugiechio," "Les Checagou" and "Les Miamis" (all Miami-speaking villages). Closer to the Mississippi River are the "Folles Avoines" (Menominee) and the "Renard Nation" (Fox). The "Outaouacs" (Ottawa) are on the southeast shore of Lake Superior. Farther north are "Les Sauteurs" and "Les Missisague" (Ojibwa villages). The map also shows French explorations far to the west, where they met the Dakota ("Issati Orientaux" on the Nadouessioux River). Nicholas de Fer (1646-1720) was a geographer, cartographer, and one of the leading publishers of maps in Paris in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. This map also shows that the French controlled trade in the Ohio, Illinois, and Mississippi River region in 1718. The Iroquois are shown east of Lake Erie. The French still referred to what is now Lake Michigan as "Lac Des Illinois," which reflects the important position of the allied Illinois-speaking villages ("Les Illinois"): Tamaroa, Metchigamias (who seem to have recently moved west). Note the French posts of Fort Louis and Fort Crevecoeur (est. 1679). The Checagou River is named after a village of Miami-speaking people ("Atchatchakangouen"). What most interested the French about this region? Note the detail of the beaver. Note the illustration of men carrying a canoe between waterways (portage). Nicholas de Fer, Le Cours de Missisipi, 1718 (Newberry Library, Ayer 133 .F34 1718).

New Map of the Western Parts of Virginia, Pennyslvania, Maryland, and North Carolina, sheet 1

Hutchins's map was the first large-scale map of the region west of the Allegheny Mountains based on first-hand observations. Hutchins was a captain in the British army. Because the British controlled the region by 1778, the French posts that appeared on the map made by Nicholas de Fer in 1718 are gone. Note the large territory (in green) referred to as "Illinois Country." Several allied villages of Illinois-speaking people are shown on this map. For example, Piorias. Nearer "Lake Michigan" (on earlier maps Lake Ilinese or Illinois) are villages of Miami-speaking people who were allies of the Illinois groups: "Ouiatanon" (Wea) and "Chikago." Note that Indian villages are near the trading posts and routes. Several of the Indian villages in the region were overlooked by Hutchins, which suggests that the British lacked the first-hand knowledge of the French. Can you locate the mines worked by the French and Indians? Can you find the Potawatomi Indians? Thomas Hutchins, New Map of the Western Parts of Virginia, Pennyslvania, Maryland, and North Carolina, 1778 (Newberry Library, oversize Graff 2029, sheet 1).

New Map of the Western Parts of Virginia, Pennyslvania, Maryland, and North Carolina, sheet 2

The map shows "Indiana," which had been sold by the Iroquois, even though they were not living there. Detroit is shown as a multiethnic center. Note the Ottawa and Wyandot villages there. Can you find the large Miami village and the towns of the Delaware and Shawnee? There is a lead mine on the map. Can you find it? Note also that many of the rivers in the region bear the names of Indian groups. Thomas Hutchins, New Map of the Western Parts of Virginia, Pennyslvania, Maryland, and North Carolina, 1778 (Newberry Library, oversize Graff 2029, sheet 2).

New Map of the Western Parts of Virginia, Pennyslvania, Maryland, and North Carolina, sheet 3

Hutchins's map shows how the American colonies already had designs on Indian country. Virginia (marked in blue) claimed the land as far west as the Wabash River in what is now Indiana, even though Indians occupied the region, and Virginia and North Carolina claimed land west to the Mississippi River. Thomas Hutchins, New Map of the Western Parts of Virginia, Pennyslvania, Maryland, and North Carolina, 1778 (Newberry Library, oversize Graff 2029, sheet 3).

New Map of the Western Parts of Virginia, Pennyslvania, Maryland, and North Carolina, sheet 4

Although Virginia claimed land all the way west to the Mississippi River, the map indicates where the "farthest settlement [west]" was in 1755. How does the map reflect the earlier importance of the French in the region? Why does the notation "path to Ottawa country" reflect the importance of the Ottawa in the fur trade? Thomas Hutchins, New Map of the Western Parts of Virginia, Pennyslvania, Maryland, and North Carolina, 1778 (Newberry Library, oversize Graff 2029, sheet 4).

For what did Indians Trade?

Native people developed or borrowed rituals to adjust peacefully to the congregation of different ethnic groups at French trade centers. For example, the calumet ceremony made symbolic kinspeople out of enemies through the transfer of a sacred pipe from one person to another. At the “feast of the dead,” people in several communities brought the remains of their dead to be re-interred in a common grave, and they exchanged gifts, which strengthened the bond between all those in attendance. Another important ritual was the Medicine Lodge, whose leaders obtained help for the faithful from spirit beings and promoted cooperation.

Habit of an Ottawa Indian

The man in the drawing is wearing a loin cloth and robe of European cloth and probably a metal gorget (medal throat or chest cover). His body is adorned by paint or tattoos and he wears trade beads. Indians shaped the trade by demanding the goods that served their interests and appealed to them culturally. Both finished clothing and materials for making clothing (awls, needles) were sought especially by women, and these trade goods reduced women's time and labor in producing clothing for their families. Clothing was as important in trade as metal tools and guns. Photo courtesy of Mackinac State Historic Parks Collection, Michigan.

Paccane, a Miami Man, 1796

Etching done by Elizabeth Simcoe, wife of the lieutenant governor of Upper Canada. This man wears arm bands, a nose ring, and ear wheels-all silver trade goods. He holds a trade tomahawk. His head is shaved except for the scalp lock, which has an ornament attached. Courtesy of Archives of Ontario (F 47-11-1-0-384).

Trade Axe, probably French from the late 1600s

Metal trade axes replaced axes made of stone because they were more durable and more easily acquired. Photo courtesy of Allen County-Ft. Wayne Historical Society.

Silver brooch, Maumee River Valley

This piece was made by Robert Cruickshank (1748-1809). He learned the silversmith trade in London, then came to Boston about 1768. A Tory, during the American Revolution he moved to Canada where he worked as a silversmith in Montreal from about 1781 to 1809. He had a large workshop with several apprentices, where he made domestic silver and large amounts of Indian trade silver. In 1799, he produced over 7,000 items. Women used brooches as fasteners for clothing and as decorations on clothing. They wore large numbers of them on their dresses. Photo courtesy of Allen County-Ft. Wayne Historical Society.

Silver cross, Maumee River Valley

Robert Cruickshank made this engraved piece. Jesuit missionaries routinely distributed crosses, crucifixes, medals, and rings made of several kinds of medal, including silver. These often were engraved with religious symbols, but eventually these items became secular ornaments. Photo courtesy of Allen County-Ft. Wayne Historical Society.

Engraved Silver bracelet or Arm Band

This was made by Pierre Huguet dit Latour (1749-1817), of Montreal. He worked in Montreal from about 1780 to 1816, producing large quantities of trade silver. This piece was found in the Maumee River Valley. Bracelets, arm bands, and leg bands were popular. Traders distributed metallic ornaments as condolence gifts at mortuary rituals and Indians used these ornaments as grave offerings. Photo Courtesy of Allen County-Ft. Wayne Historical Society.

Silver Gorget

Robert Cruickshank made this circular gorget or breast plate. The gorget has two studs at the upper curve for securing loops on the back of the piece. European officials gave gorgets and medals to important leaders in order to keep their allegiance. These objects had high prestige value and aspiring leaders sought them. The likeness of the coat of arms of a monarch might be engraved on gorgets or medals. Europeans also wore gorgets. Originally they were part of plate-armor worn by nobility. After armor no longer was worn, the gorget was retained as a symbol of rank. Photo courtesy of Allen County-Ft. Wayne Historical Society.

Copper pot

This pot was found near Miami Town and was used from the 1780s to about 1810. Copper pots replaced pottery and other containers because the metal pots were more durable and easily replaced. Photo courtesy of Allen County-Ft. Wayne Historical Society.

Copper pot, Hudson Bay Style, 18th Century

This pot is possibly from the Maumee River Valley area. When a pot was no longer needed, the metal would be reused to make tools and weapons. Photo courtesy of Allen County-Ft. Wayne Historical Society.

Necklace, Made of Glass, Stone, and Shells

It was found near Miami Town. Such a necklace was a valued trade item, probably made by an Indian craft worker using trade beads. Photo courtesy of Allen County-Ft. Wayne Historical Society.

Listen to one of the ojibwa accounts of the origin of the medicine lodge

Midewewin Lodge. Video courtesy of WDSE-Duluth/Superior, MN. View transcriptThe fur trade also resulted in an intensification of warfare among Native peoples, who competed for access to the French. East of Lake Huron, Iroquois people obtained guns and began to expand west, making war on the peoples trading with the French in order to gain control of the trade themselves.

During the Beaver Wars of the 1630s through the 1650s, the Iroquois displaced the Wyandot, forcing their dramatically reduced population westward. The French established Montreal in 1642, and by the 1680s the Ottawa, who lived west of the Wyandot, assumed the middleman role. Ojibwa contacts with French traders and their acquisition of the gun led to their expansion south into Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan. In present-day Minnesota they came into contact with the numerous Dakota, who tried to hold their territory. The entire Great Lakes region was a war zone in the 17th century. In 1701 peace was negotiated with the Iroquois.

In the mid-18th century, Native peoples were living peacefully in a multiethnic region where Indians, Europeans, and mixed ancestry (Métis) people all contributed to the regional economy and cooperated. But ultimately the French and English empires drew Indians into their quarrel over who would control the Great Lakes region. War erupted in 1754 in Ohio. The conflict resulted in warfare among Indians, population dislocation, and numerous villages of refugees. Alliance with the French was attractive because they did not want to settle on Indian lands and they behaved as generous kinspeople. The British won some support by offering to stem the tide of trespassing colonists crossing westward beyond the Appalachian Mountains. But after Britain prevailed over France in 1763, Indian leaders saw with dismay that the trespasses continued. In 1763 the Ottawa warrior Pontiac led a short-lived regional, multi-tribal independence movement, supported by a new religion that drew on spirit beings for help.

Do you want to learn more about warfare?

Attack on Fort Michilimackinac by Pontiac's Followers

Pontiac was born in 1720 in a village near what is now Detroit. He grew up in a multiethnic community. His father was Ottawa and his mother was Miami or Ojibwa. His village was loyal to the French during the French and Indian War. By 1762, Pontiac had an outstanding reputation as a warrior and he was an eloquent speaker. Pontiac's village found British administration onerous. He formed an association with Neolin, a Delaware prophet, who was preaching that messages from spirit beings mandated a return to "traditional ways" and a rejection of British trade goods. With the backing of the prophet and promises of help from the French, Pontiac met with warriors from villages throughout the Great Lakes area and then launched an attack on British forts in 1763. He led followers in an attack on Fort Detroit in May. Elsewhere, his followers attacked forts in Ohio, Michigan, and Indiana. Ojibwa and Sauk made the attack on Fort Michilimackinac. As illustrated in the drawing, they pretended to play ball and when the ball went into the fort they continued the game there. They attacked once inside the fort, taking the British by surprise. Pontiac's followers captured 8 of 12 forts and forced the abandonment of a ninth. But the French made peace with the English and withdrew their help. Pontiac subsequently lost stature among his followers. He left the Michigan and Ohio area and went west among the Illinois, where he was assassinated in 1769. Raymond McCoy, The Massacre of Old Fort Mackinac (Newberry Library, Ayer 150.5 .M57 M13 1940).

Wingenund's War Record

Indian men kept bark pictographic records of their war experiences. Wingenund was a Delaware war leader who joined Pontiac in the 1763 rebellion against the British. Seth Eastman's drawing shows the symbol of Delaware ethnic identity (the turtle), a symbol for Wingenund's spirit helper (#2), the sun (#3), and (on the right) 10 horizontal lines representing ten war parties. On the left are his accomplishments during each war party. These stick figures show men and women killed or taken prisoner. He participated in the capture of a fort on Lake Erie (#8), the siege of Detroit (#9), the attack on Fort Pitt (#10), and an attack on a town near Detroit (#11). Drawing by Seth Eastman in Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, Historical and Statistical Information, Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States (Newberry Library, Ayer 250 .S3h 1851, v. 1, pl. 47, fig. B).

The Figured Stone or Shing-Gaa-Ba-Wosin

This portrait was painted by James Lewis in 1826 at the Treaty of Fond du Lac when The Figured (or Image) Stone was 82. He was a distinguished Ojibwa warrior who attended treaty councils in his old age. He received a presidential medal (a medal with the president's image on it) for his treaty council participation. He lived at Sault Ste. Marie but spent much of the time hunting and fishing west of Lake Superior. He died in 1828. Drawing by Seth Eastman in James Otto Lewis, North American Aboriginal Port-folio (Newberry Library, Ayer 250.6 .L67 1838, no. 1).

Grave post of Shing-Gaa-Ba-Wosin or The Image Stone

On his carved post is his family [clan] symbol, the Crane-here upside down to indicate death. On the right are 6 horizontal "marks of honor" that indicate battles in which he distinguished himself, including those he fought as part of Tecumseh's warriors. On the left, the three horizontal bars represent three treaty councils in which he participated as an Ojibwa spokesman. He was opposed to land cessions but by the 1820s had realized that military resistance was futile. Drawing by Seth Eastman in Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, Historical and Statistical Information, Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States (Newberry Library, Ayer 250 .S3h 1851, v. 1, pl. 50, no. 4).

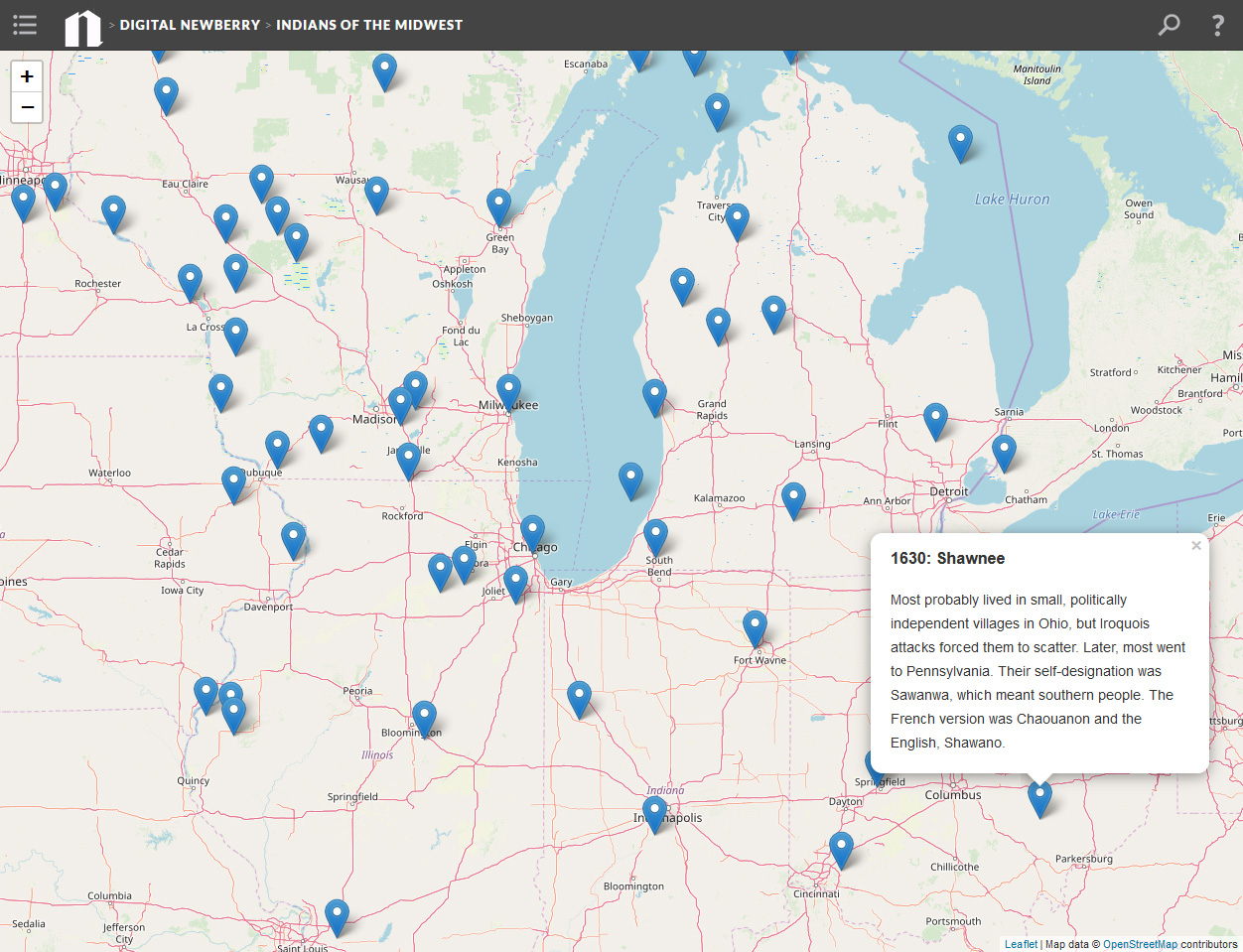

Interactive map: Explore trading post locations

Jolliet and Marquette Visit the Great Village of the Illinois

In the summer of 1673, a French expedition led by Louis Jolliet, a young French Canadian fur trader, and a Jesuit priest, Jacques Marquette, reached two villages of Illinois-speaking Indians. This expedition by seven men in two birchbark canoes descended the Mississippi River to the mouth of the Arkansas River, then returned to the Great Lakes by way of the Illinois River. They visited a Peoria village near the Mississippi River and a Kaskaskia village on Illinois River in north-central Illinois. Note that Marquette is offering a calumet. Their report was the earliest first-hand account of the Illinois Indians. The voyage of Jolliet and Marquette paved the way for French expansion into Illinois country. Robert A. Thom painting, 1967, imagined from documentary sources, but the calumet was presented by the Illinois to the two Frenchmen, not by Jolliet to the Illinois. When Marquette and Jolliet left the Illinois village, they were given a calumet to see them safely through the territory of other groups. Reproduction courtesy of the Illinois State Historical Society.

White Trader with Ojibwa Trappers, ca. 1820

This painting shows a trader meeting with an Ojibwa winter hunting party with furs to trade. The Ojibwas are wearing wool garments and carrying guns and metal knives—all products of European manufacture. Note also that items made by Ojibwas still are in use, such as fiber bags and snowshoes. This is a watercolor, gouache over pencil; artist anonymous. Courtesy of Royal Ontario Museum.

Meda Scroll, Medicine Lodge

The pictographs on the board symbolized spirit encounters. They served as mnemonic devices for rituals and songs of the Medicine Lodge, a new religion that emerged in the 17th century. It essentially was a society of people who had acquired through apprenticeship the knowledge to cure illness. The leaders (Meda) helped followers maintain good health—more difficult after Europeans brought new diseases for which Indians had no immunity. The leaders also used their influence to persuade people to cooperate with political leaders who were working to develop partnerships and alliances between villages. The Medicine Lodge religion was embraced by all the Native groups in the region. Drawing by Seth Eastman in Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, Historical and Statistical Information, Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States (Newberry Library, Ayer 250 .S3h 1851, v. 1, pl. 51).

Ojibwa-Fox Battle

The Ojibwa and the Fox competed for access to French trade goods. This drawing by Seth Eastman illustrates events that followed a Fox raid on the Ojibwas at La Pointe. The Ojibwa pursued the Fox across Lake Superior, and they fought from their canoes. The former greatly outnumbered the Fox and defeated them. Eventually the Ojibwa forced the Fox from the area, probably in the early 17th century. Drawing by Seth Eastman in Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, Historical and Statistical Information, Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States (Newberry Library, Ayer 250 .S3h 1851, v. 2, pl. 32).

Iroquois Wars, 1641-1701

During the Beaver Wars (1630s-50s), the Iroquois attacked into the Ohio River valley, eventually driving the Algonkian-speaking groups living there out of present-day Ohio and Michigan. In Wisconsin and Minnesota the survivors of Iroquois raids congregated in contiguous villages or in multiethnic villages, often near a French post, to try to defend themselves with help from the French. Note that the Iroquois reached the country of the Illinois-speaking villages and fought major battles there (X). Forts are indicated by squares and Indian villages by triangles. Ethnic group abbreviations: IL (Illinois); OT (Ottawa); TI (Tionontati, refugees and allies of Hurons); SH (Shawnee); MI (Miami); MES (Fox); MC (Mascouten); PO (Potawatomi); KI (Kickapoo); SA (Sauk); WI (Winnebago); OJ (Ojibwa); ME (Menominee); HU (Huron). Detail from Map 6 in Helen Hornbeck Tanner, ed., Atlas of Great Lakes Indian History (Newberry Library, Ayer folio E78.G7 A87 1987).

Susan Johnston (Oshawguscodaywayqua)

Susan Johnston (Oshawguscodaywayqua) was born in 1772, the daughter of Waubojig, an important Ojibwa chief from La Pointe,Wisconsin. She married John Johnston, an Irishman who was a trader among the Ojibwa for forty years. James Lewis painted her portrait in 1826. She wore a cloth petticoat and gown, and beaded leggings and moccasins. She knew Ojibwa leaders and European traders and was a respected and influential person in her region in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. She had seven children, and one daughter married the Indian agent Henry Schoolcraft. Mrs. Johnston was one of many women married to Europeans and Americans who contributed to the success of multiethnic, multi-racial relationships. Her children were part of the Métis community. Thomas Loraine McKenney, Sketches of a Tour to the Lakes (Newberry Library, Ayer 128.7 .M25 1827).

Frederick Faribault, Métis

Faribault’s family was in the Indian trade. His father, Jean Baptiste, was a French-Canadian trader who worked out of Prairie du Chien. Jean Baptiste Faribault married Pelagie, a Métis woman whose mother was Dakota. The family was “Creole,” that is, their way of life was a blend of Indian and Euro-American custom. For example, Creole communities practiced both European methods of farming and worked in the fur trade. Frederick was about 25 when Frank Blackwell Mayer sketched him in 1851. Drawing by Frank Blackwell Mayer in Frank B. Mayer collection of sketchbooks, drawings, and oil paintings of Sioux Indians during the 1851 treaty negotiations at Traverse des Sioux and Mendota, Minn. (Newberry Library, oversize Ayer Art Mayer, sketchbook #42, p. 102).

-

1

2021-04-19T17:20:02+00:00

Ownership

1

image_header

2021-04-19T17:20:02+00:00

Above: Meda meeting in secret, opening their medicine bundles. Drawing by Seth Eastman in Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, Historical and Statistical Information, Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States (Newberry Library, Ayer 250 .S3h 1851, v. 5, pl. 5). View catalog record

Native people in the Great Lakes area recognized individually-owned property. Women and men owned their own tools, clothing, ornaments, and any gifts of property they received. Ojibwa husbands and wives owned property separately but lent their possessions to each other. These ideas about gender and property contrasted with those in colonial and early 19th century America, where married women could not own property. Native children owned their toys and clothing, so parents did not have control over their children’s property.

What kind of property did they own?

Rush Mat, Sauk and Fox

Women made and owned these mats. This one is woven with nettle fiber cord and dyed with botanical substances from the forest. Rows of deer form the design. Photo courtesy of the Field Museum (#34989, neg. A110957c).

Woman Weaving Rush Mat

Shown here is Mrs. Gurneau at Red Lake, Minnesota making a floor mat. Women could work on these mats only early in the morning or evening when the air was moist so the reeds would not dry out and become brittle. Mrs. Gurneau made the bark frame herself. Frances Densmore, Chippewa Customs, 1929 (Newberry Library, Ayer 301 .A5 v. 86, pl. 1).

Woman's Pipe

Women's pipes were made of black stone, and men's of red stone. The stem was wood. This pipe is for everyday smoking (bark and/or tobacco) and is about 7 inches long. Pipes for formal use had longer stems, and ceremonial pipe stems could be 3 feet long, and they were elaborately decorated. Frances Densmore, Chippewa Customs, 1929 (Newberry Library, Ayer 301 .A5 v. 86, pl. 52a).

Knife case, Dakota Sioux

Men owned their knives and the cases (made by women and given to men). This case is decorated with bird quills. It is almost 10 inches long and a little over 3 inches wide at the top. It was collected by Frank Blackwell Mayer at the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux in 1851. Photo courtesy of the Field Museum (#12976, neg. A110272_Ac).

Bow and Bird Arrow

Men made and owned their bows and several different kinds of arrows, depending on the game they were hunting. The bird arrow was made of hickory and was used for hunting birds. Paul Radin, The Winnebago Tribe; 37th Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 1915-16 (Newberry Library, Ayer 301 .A2, pg. 118, pl. 31).

Infant with Ornamented Cradle Board

Women made cradle pouches for babies before they were born, and the baby's navel cord was placed in a small bag and tied to the cradle, as were small toys, including strings of beads, little bones, shells, birchbark cones, and feathers. Men usually made the frame. The mother's in-laws brought her gifts and the father gave a feast for a spirit being as thanks for the healthy child. Paul Radin, The Winnebago Tribe; 37th Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 1915-16 (Newberry Library, Ayer 301 .A2, pg. 121, pl. 42a).

Individuals also owned intangible property, often associated with power received in a dream vision. Youths fasted in isolation for a vision in which a spirit helper granted them various powers (in hunting, war, and curing, for example). Ojibwa girls also had dreams in which they acquired power. Associated with the power were objects (for example, a medicine bag), names, and songs given by the spirit helper that symbolized the power of the vision. The power was not effective without the supernatural connection with the spirit. And the owner had to feed the guardian spirit with tobacco and food to maintain the relationship.

Members of the Medicine Lodge (“meda” or “mide”) acquired a medicine bag and other objects upon initiation. They could pass the bag on to a new initiate (for a fee) or dispose of it whatever way they chose.

Some property was owned not by individuals but by groups. Individual clan members served as custodians of clan-owned medicine bundles. Among the Ojibwas, the Dream Dance ritual was owned by groups (possibly residential or family groups or villages). Sometimes, Ojibwa villages owned dances they purchased from other tribes: the village leader was the custodian of the dance.

Land and the resources on it were not “owned” by either groups or individuals. People had “use-rights” to places where they would garden, fish, harvest rice and berries, and tap for sugar. As long as they used these resources, they had a right to them. Villages that had use-rights in a territory permitted others to hunt, fish, and gather there. Even after Americans imposed allotments and legal title to land, the resources on the land continued to be viewed by Indians as associated with use-rights.

Native people valued property as a means of strengthening social bonds. It was never to be accumulated by individuals or groups while other community members went without. Food was always shared with kin and needy members of the community. When a man killed a deer, he shared the meat by hosting a feast. After a group hunt, the meat was divided among the hunters and their families. Community feasts were frequently held when food was harvested or spirit helpers honored. Clans regularly feasted each other. Tools, clothing, and other items were given to others as gifts, sometimes to reinforce friendship and sometimes to meet a kinship obligation.

Obligations to relatives continued after death. Family members dressed the corpse in fine clothing and jewelry and often buried his or her prized possessions with the deceased. Above the grave, many groups erected a grave house with a ledge where they brought tobacco and food to feed the soul of the deceased person for his or her four-day journey to the Afterlife. Property that might be useful for the journey might be left at the grave or buried: weapons, tools, moccasins, cooking and eating utensils. Food was brought to the grave subsequent to these mortuary rituals, as well. These gifts could be used in the Afterlife by the deceased to establish good relationships there. The bereaved would be helped to go on with their lives by annual or periodic attention from others, including gift-giving.

Learn more about mortuary ritual

Grave Post of Shing-Gaa-Ba-Wasin (The Image Stone), Ojibwa Warrior

On his carved post is his clan symbol, the Crane, upside down to indicate death. On the right are six horizontal "marks of honor" that indicate battles in which he distinguished himself. On the left, three horizontal bars represent three treaty councils in which he participated. Grave posts with an inverted clan symbol continued in use well into the latter half of the 20th century. Drawing by Seth Eastman in Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, Historical and Statistical Information, Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States (Newberry Library, Ayer 250 .S3h 1851, v. 1, pl. 50, no. 4).

Feeding the Dead

Scaffold burials were used, as well as interment, until lumber became available for grave houses. Relatives brought food to the soul (ghost or spirit) of the deceased. The ghost ate the spiritual essence of the food, and members of the community could take the food to eat. Food was offered each day during a four-day mortuary ritual, and families usually would bring food periodically for some time afterwards to maintain good relations with the soul of the deceased. Feeding the dead was common to virtually all the Great Lakes Native communities. Drawing by Seth Eastman in Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, Historical and Statistical Information, Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States (Newberry Library, Ayer 250 .S3h 1851, v. 1, pl. 3).

Ojibwa Grave Houses, 1925

This cemetery at Leech Lake shows the ledge on the grave house where food was placed, the grave posts, and some property left for the deceased. Before the 19th century, bodies were buried wrapped in bark and covered with a small mound or bark, or the body was put on a scaffold or in a log enclosure. The grave post with inverted clan symbol was placed by the grave. When lumber became available in the 19th century, grave houses with ledges for food offerings were commonly built over interments. Even Christian converts had this kind of burial. Photo by Huron Smith, courtesy of Milwaukee Public Museum.

Today, feasting and gift-giving are important rituals in Native communities. They serve to strengthen the bonds between living people and between the living and the dead. For example, the Ottawa hold “Ghost Suppers” once a year at several settlements. People come together to feast and honor their deceased relatives. At community powwows throughout the Midwest, families give away property to visitors to honor relatives participating in the powwow and to establish friendly relations with non-members of the community. Food also is often distributed to these visitors. And helping others with food and other kinds of economic assistance still is a central value in Indian communities.

Read the instructions a Ho-Chunk elder gave a youth about generosity. Note how generosity is supernaturally sanctioned.

My son, when you keep house, should anyone enter your home, no matter who it is, be sure to offer him whatever you have in the house. Any food that you withhold at such time will most assuredly become a source of death to you. . . . If you see an old, helpless person, help him with whatever you possess. Should you happen to possess a home and you take him there, he might suddenly say abusive things about you during the middle of the meal. You will be strengthened by such words. This same traveler may, on the contrary, give you something that he carries under his arms and which he treasures very highly. If it is an object without a stem [medicine plant], keep it to protect your home. If you thus keep it within your house, your house will never be molested by any bad spirits. Nothing will be able to enter your house unexpectedly. Thus you will live. From Paul Radin, The Winnebago, 37th Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 1915-16, p. 170.

Bear Medicine Cloth

A man from Mille Lacs owned this medicine (the power to cure), which he received when he obtained a spirit helper in a vision. The bear spirit was his helper and he kept a representative drawing on a piece of cloth. The man’s wife became very ill, so he spread the cloth over her so that the strength of his bear spirit helper would transfer to her. She improved, then he put the cloth on the wall above her head until she recovered fully. This kind of personal medicine was owned by both men and women among the Ojibwa. Frances Densmore, Chippewa Customs, 1929 (Newberry Library, Ayer 301 .A5 v. 86, pg. 83, pl. 32a).

Winnebago Mide at Medicine Lodge

Here, the Mide or Meda, who cure patients and assist the souls of the dead in their journey to the Afterlife, are using their medicine bags as they conduct ceremonies in the Lodge. Painting by Seth Eastman in Mary H. Eastman, The American Aboriginal Portfolio (Newberry Library, Ayer 250.45 .E2 1853).

Meda meeting in secret, opening their medicine bundles

Each man owned his bundle. His right to do so was purchased when he was initiated into the Medicine Lodge. Drawing by Seth Eastman in Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, Historical and Statistical Information, Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States (Newberry Library, Ayer 250 .S3h 1851, v. 5, pl. 5).

Ho-Chunk Bear Clan Police, Black River Falls, Wisconsin, ca. 1900

These members of the Bear Clan are holding batons of authority, which were clan property. The Bear Clan has always been responsible for keeping order. They supervised hunts and camp movements, dealt with wrongdoers, and generally policed public gatherings. Each Ho-Chuck clan owned a war bundle (formerly owned by families and used for success in war, then gradually associated with the clan and used to pray for success in life generally). The Bear Clan owned a war bundle, war clubs, two crooks used in battle, and batons of authority. There are twelve clans and, today, seven or eight active war bundles. Photo by Charles Van Schaick, courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society.

Ojibwa Dream Dance Drum, 1899

This is one of three drums at this ceremony at Lac Courte Oreilles. The drums were owned by residential communities on the reservation. Ojibwa groups transferred drums to groups from other tribes, including the Menominee, receiving gifts in return. The Menominees organized dream dance societies, each of which had a drum. The keeper of the society’s drum had to be qualified in the eyes of the society members. Courtesy of National Anthropological Archives (NAA INV 00255400).

Treaty of 1837

The Ojibwa groups who signed the treaty at St. Peters on July 29 insisted on retaining the right to hunt, fish, and gather throughout the area they ceded in Wisconsin and Minnesota. From Ratified Indian Treaties, National Archives Microfilm Publication (Newberry Library, Microfilm 152, roll 8).