How We Know

Above: Obsidian Points. Courtesy of the Field Museum

Historians and anthropologists (including archaeologists, ethnographers, and many linguists) have tried to describe and understand continuity and change in Native societies both prior to and after European arrival. In recent years, ethnographers, who conduct research in communities, have tried to explain how present-day innovations are related to long-held Native values and understandings as well as global developments. All these scholars obtain information in a variety of ways, including using accounts of oral historians and Native writers, then interpret that data to arrive at explanations.

How do archaeologists interpret the meaning of the earthworks that were the focus of religious ceremonies long before Europeans arrived on this continent? One approach is to study the belief systems of the Native peoples who met the first Europeans and see if these ideas are reflected in sacred landscapes. Consider the effigy mounds. The forms of these sculptures in Wisconsin seem to be compatible with the depictions of spirit beings in the origin stories of people such as the Ho-Chunk and Menominee, who have lived in this region since before the arrival of Europeans. For example, the “lizard” figure fits Winnebago accounts of the “water serpent” in the early twentieth century. In the cosmology of these peoples, the world has Upper and Lower dimensions. The Upper World has spirit beings associated with the Sky, and beings of the earth and water are associated with the Lower World. Rituals work to maintain balance between these dimensions and to maintain good relations with the spirit beings who control food resources in their respective realms.

The mound clusters in Wisconsin represent this belief system. Note that in the illustration “Effigy Mound Distribution” the majority of the bird-shaped effigy mounds are in the upland region of western Wisconsin (near the Mississippi River route of millions of migratory birds). Effigies of bears and other land-dwelling animals are most frequent in central Wisconsin. Effigy mounds of the water spirit type are in the eastern part of the state, close to wetlands. On virtually every site of a mound cluster there is at least one representative of the opposing realm. Where there is a cluster of birds, there will be at least one water spirit mound. This distribution symbolically maintains balance. Archaeologists also link the mound symbolism to the social organization of groups like the Ho-Chunk and Menominee, whose people were organized into Sky and Earth divisions. Each division had family groups or “clans” that belonged to it, and people in the Sky division had to marry people from the Earth division and vice versa. The Sky division had the Thunderbird, Eagle, and Hawk clans. The Earth division had the Bear, Buffalo, Deer, Snake and Water Spirit Clans.

What other evidence do archaeologists draw on to link historic peoples to the moundbuilder sites? If archaeologists excavate a site and find deposits of objects with no European association and these are later covered with deposits of European objects, they might establish a link between the people living there before contact with Europeans and those whose descendants are living today. But these sites are difficult to find in the Midwest. The research of linguists offers another type of information.

When groups of people who speak the same language move away from each other and remain apart for a long time, they develop different dialects then, over time, lose the ability to readily understand each other. They eventually speak different languages. Linguists compare languages to calculate how many years probably passed for distinct languages to develop from an original or “proto” language. They compare basic vocabulary terms for native plants or numbers or natural features such as water. The more similarity there is, the more recently the speakers spoke the same language. The more dissimilar the terms, the longer the time the speakers of the languages were apart. “Proto-Algonkian” was the original language spoken by groups including Ojibwa, Ottawa, Potawatomi, Menominee, Miami, and Shawnee. Linguists theorize that about 3,000 years ago their original homeland was west of Lake Ontario in what is now southwestern Ontario Province in Canada. From there, Ojibwas moved west, the Potawatomi moved to the east of Lake Michigan, the Menominee moved to west of Lake Michigan, and the others moved farther south into Illinois and Indiana. Other Algonkian speakers traveled far to the east. Eventually the Algonkian-speaking groups in the Midwest developed different languages or different dialects of languages. Some of their vocabulary shows evidence of more recent borrowing from Siouan speakers.

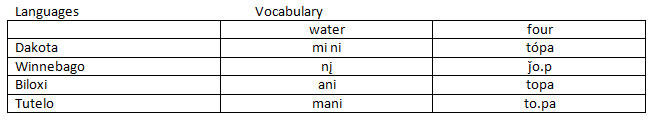

The Proto-Siouan homeland probably was in the Ohio River valley. There, 3,000 years ago, lived the ancestors of the Winnebago (Ho-Chunk) and Dakota, who would have been associated with the ceremonial centers in Ohio. Over time, groups migrated to the southeast (for example, the Tutelo to Virginia), to the south (the Biloxi to Mississippi), and others to the Cahokia region, then to the north up the Mississippi River (the Winnebago and Dakota), or farther west. Note the similarities between Dakota, Winnebago, Biloxi, and Tutelo:

Linguists also look for borrowed words or new vocabulary in languages. These new words may indicate significant contact between people, as well as something of the nature of interpersonal relations.

Listen to Raymond Demallie discuss how the Dakota language changed after the Dakota began interacting with Europeans

Historians and ethnohistorians (who use approaches of both anthropologists and historians) rely on primary sources to document what has happened in the past. What are primary sources? People write letters and reports, publish newspapers, sit for photographs, grant interviews, draw maps, take censuses, and make drawings. Historians studying a particular time period look for documents like these “primary” ones that were produced then. They try to learn what went on and also how different individuals and groups viewed events and interacted. Black Hawk’s autobiography sheds light on his actions in 1832. In another example, historians studying the fur trade have learned much from journals of fur traders such as Joseph Marin, a French official and trader in the mid-18th century. Marin recorded his efforts to use gifts to attract trade and to prevent Indian wars that made trade difficult. As Marin’s journal shows, the highest ranking French official had the kinship role of “father” to his Indian allies.

Do you want to read an entry from his journal?

September 5, 1754. I arrived at eight o’clock in the morning at the village of the Puans, they came to meet me with peacepipes and saluted me with a lot of shots. I had their salute answered with three shots and went off to camp across from their village in the accustomed spot. They came to pay me their compliments. After answering them on the fine reception they gave me, I gave them the usual presents and told them the news. And I told them in the Council that I had heard that there were some young men singing War and if that was true, they had better tell me and that they were very wrong because they knew that it was not the wishes of their father Onontio that His children make war on each other; they answered that it was true and they didn’t want to hide anything from me; that Yellow Thunder, war chief of the village, was on the point of leaving with 60 young men to go make war against the Illinois. . . . Then I sent for the war chief and spoke to him alone. I gave him some gifts for his young men and told him I didn’t want him leaving to do bad business; and all he really had to think about was hunting well all winter long to try to provide for his family’s needs, and that that was better than going to war against my wishes and those of his chiefs, which could cause him to be hated by his Father the General, and that would do him no good at all. He answered that it was true that they wanted to go, but since I told him not to go against my wishes, he would stay quiet on his mat. From Journal of Joseph Marin, ed. and trans. Kenneth P. Bailey, c1975, pp. 53-54.

Ethnographers spend time in Indian communities observing and talking with people to try to understand the way of life and the ideas people have in these communities. One of the ways these anthropologists try to understand change is by working with autobiography. Nancy Lurie’s autobiography of a Ho-Chunk woman (1884-1960) is one of the best examples. This individual, whose name was Mountain Wolf Woman, joined the Medicine Lodge, then became a follower of the peyote religion. Lurie observed first-hand the major changes in Ho-Chunk life. She recorded the life story in the Winnebago language, then Mountain Wolf Woman repeated it in English. Lurie uses her research in the Ho-Chunk community to contextualize the incidents in the autobiography and to show how “characteristic and recurrent [Ho-Chunk] themes underlie her [Mountain Wolf Woman’s] opinions, decisions, and behavior.”

Read an excerpt from the life story and Lurie’s commentary on it.

Mountain Wolf Woman: I was very sick and my mother wanted me to live. She hoped that I would not die, but she did not know what to do. At that place there was an old lady whose name was Wolf Woman and mother had them bring her. Mother took me and let the old lady hold me. “I want my little girl to live,” mother said, “I give her to you. Whatever way you can make her live, she will be yours.” That is where they gave me away. That old lady wept. “You have made me think of myself. You gave me this dear little child. You have indeed made me think of myself. Let it be thus. My life, let her use it. My grandchild, let her use my existence. I will give my name to my own child. The name that I am going to give her is a holy name. She will reach an old age.”

Nancy Lurie: To give away relates to the idea that highly valued possessions are given away rather than saved. Thus, children may be given away in the sense of honoring rather than rejecting the child. Sometimes a child is requested because he reminds a bereaved parent of a dead child and such requests cannot be refused. In any case, the child usually continues to live with his own parents but may claim certain benefits from the person to whom he is given as well as acquire certain obligations toward that person. In the instance noted, the child herself became, in effect, the payment for her own cure, the most precious object her mother could tender. The story indicates the esteem in which she was held. A number of highly esoteric concepts are involved in the old woman’s statements. “You have made me think of myself” is a direct translation of the Winnebago, and expressed in English in these same words by both Mountain Wolf Woman and my translator, Mrs. Wentz. The phrase suggests both the sense of being honored and the sense of pondering the meaning of one’s own existence. Any gift, furthermore, carries the requirement of a return gift of equal value. Therefore, the old woman cured Mountain Wolf Woman not by the usual and simpler expedient of herbal medicine alone but by the proffer of her own life and longevity. The basis of her statement is the fundamental belief that the proper life span of a human being is one hundred years. Thus, at wakes the deceased is asked to distribute among his relatives his unused portion of good things from his remaining years. The old woman made this type of bequest, but the statements also carry the implication that she is able to share the force of her personal power before her death. Finally, the bestowal of a name from her clan implies benefits to the recipient of the name. Clan names are sacred in nature and given lists of names are the property of each clan. The name signifies the protection of the clan spirit. From Nancy Oestreich Lurie, Mountain Wolf Woman, University of Michigan Press, 1966, pp. 6, 114-15.