Are Midwest Indians Typical?

Above: Wounded Knee Memorial Ride, 2011. Photo by Duane Kuntz, Great Plains Examiner

The potential for economic development on reservations differs widely depending on the reservation’s location and access to resources. Great Lake tribes have been able to take full advantage of the federal government’s support for tribal sovereignty because they had a history of participation in the regional economy and treaty-guaranteed access to significant natural resources that could be developed commercially. Compared to tribes that do not have this tradition—and the upland Plains tribes are a good example—the Great Lakes tribes have a higher living standard and better employment history. In 2000, the median per capita household income for reservations in Montana, Wyoming, and South Dakota was $21,302. On Minnesota reservations, the median was $26,250, and on Wisconsin reservations, $26,842 (higher for tribes in the more urbanized southern part of these states).And a comparison of unemployment rates in 2005 shows that the median unemployment rate was 73% on the Plains reservations. In Minnesota, the median unemployment rate on reservations was between 26% and 39%, and on Wisconsin reservations the median was 62%.

Why has economic development been more difficult for Plains tribes? First, both the Plains subsistence and commercial economy was based on buffalo-hunting, and, when the buffalo became virtually extinct in the last quarter of the 19th century, the Plains tribes had little option but to rely on rations and provisions provided by treaties and agreements with the United States.

Second, the upland plains is very arid (which makes farming very difficult), and it is remote from major population centers that could support businesses or offer employment. Here, Indian casinos, for example, are small, minimally profitable enterprises. Still, the large reservations had grazing land, so a transition to ranching was the best hope for self-sufficiency.

Tribal members worked with determination to make this transition to ranching, building on their knowledge of herding and skills as horsemen. But they faced overwhelming obstacles. The policy of the federal government vacillated between supporting and discouraging ranching. Indian ranchers in the 1890s built up their herds and sold beef to the agencies and to the eastern markets. But in the 20th century, federal policy encouraged the leasing of reservation grazing land to non-Indian cattlemen. Sometimes virtually all the reservation grazing land was leased, and at below market prices. Indians worked as cowboys and farm laborers for low wages. During this time federal policy also promoted the allotment of reservation land to individuals and the sale of unallotted land to non-Indians at below market value. Federal agents encouraged allottees to lease their allotments, and many allottees were given fee patents on their land, which they then sold. Indian and non-Indian owned land was “checkerboarded,” so that Indians could not accumulate sufficient pasture to raise cattle. By the time of the New Deal, there was little grazing land left for Indian operators. From 1934 through the 1940s, federal policy encouraged ranching, even helping to purchase land and set up loan programs. But during the “termination” era of the 1950s, many of the gains were lost. So despite high interest in ranching and efforts by tribal governments to promote cattle operations, today only a minority of tribal members own ranches, which often are not large enough to support a family.

Images of Buffalo Days

Capturing Wild Horses

George Catlin (1796-1872) made this painting when he traveled with the Comanche in 1832. The Comanche were particularly skilled in capturing these horses, which were especially numerous on the southern plains. They used a rawhide lasso over the horse’s neck to slow the speed of the horse, then the hunter dismounted and held the horse with the end of the lasso while he fastened hobbles on the horse’s forefeet. He put a noose around the horse’s lower jaw. These wild horses were tamed by tiring them out. The Comanche obtained horses about 1705 and began to trade them to groups to the north along the Rocky Mountains. George Catlin, North American Indians: Letters and Notes on their Manners, Customs, and Conditions (Newberry Library, Ayer 250 .C2 1926, v. 2, pl. 162).

Blackfeet Indians on Horseback

Karl Bodmer (1809-93) drew Blackfeet riders during Prince Maximilian’s expedition to Fort McKenzie (at the mouth of the Marias River) on the upper Missouri River in 1833. Note that the rider carries a muzzle-loading gun, lance, bow and arrow, and is using a saddle blanket made from a mountain lion skin and lined with red strouding trade cloth. He also has clothing decorated with the red cloth. When these Plains tribes acquired the horse and transitioned from pedestrian to equestrian buffalo-hunting, they prospered. Acquisition of the horse enabled Plains hunters to obtain more buffalo meat. They could go where the herds were and bring back meat to their camps, which might be far from the herds. A horse was specially trained for hunting, for war, and for transport. Camps moved in order to provide their horse herds with water and grass. Boys watched over and moved horses during the day. The lead mare could be hobbled in order to minimize straying, and at night the best horses would be picketed near the owner’s tepee. Surplus buffalo meat and hides could be traded for goods, such as guns, metal tools, and cloth, items which made Indians’ lives easier. Engraving with aquatint (#19), after Karl Bodmer in Prinz Maximilian von Wied, Voyage dans l’Intérieur de l’Amérique de Nord, 1840-43 (Library of Congress E165 W66).

Indians Hunting Buffalo

Karl Bodmer witnessed a buffalo hunt at Fort Union (at the mouth of the Yellowstone River) on the upper Missouri River in the summer of 1833. This was probably an Assiniboine hunt. The hunter rode alongside a buffalo, firing arrows or throwing his lance. A single hunter could kill several buffalo during a buffalo chase. Men’s societies policed the communal hunts so that individuals did not undermine the success of the hunt for everyone. The horse was trained to avoid the horns and to maintain position without reins, and it could run faster than the buffalo, so that the buffalo would tire. From the buffalo, the Indians obtained food, housing, clothing, and tools. Buffalo meat was sun dried and preserved for lean times. Women tanned buffalo hide for robes, some clothing, and containers, as well as saddle blankets, and the rawhide was made into shields, ropes, containers, saddles, and stirrups. The dried buffalo droppings served as fuel and absorbent material in cradles. The horn made good spoons, and the sinew was used for thread and bow strings. Tools could be made from buffalo bone and glue from hooves. The Indians used buffalo hair to stuff saddle blankets and pillows and to make rope and horse bridles. Engraving with aquatint (#31), after Karl Bodmer in Prinz Maximilian von Wied, Travels in the Interior of North America, 1832-34 (Newberry Library, oversize Graff 4649).

Winter Hunt

The artist George Catlin traveled to the Upper Missouri region in 1832. Here he portrays Indians on the northern plains hunting buffalo in the winter with snowshoes made of wood and rawhide. In deep snow, the buffalo could not move fast and could be killed with a lance. Men hunted buffalo in the winter primarily for robes because the coat was thickest then. In the fall, after the buffalo grazed all summer on rich grasslands, the hunters obtained meat for fall and winter. George Catlin, North American Indians: Letters and Notes on their Manners, Customs, and Conditions (Newberry Library, Ayer 250 .C2 1926, v. 1, pl. 109).

Fire Bug That Creeps, Assiniboine Woman

George Catlin painted this woman’s portrait in 1832. She was the wife of Pigeon’s Egg Head, an Assiniboine man who had visited Washington DC as a member of a delegation. She wears a dress of mountain sheep skin and is holding her elaborately decorated digging stick. Women furnished plant food for their families, and digging sticks were important tools for this activity. Prairie turnips were a sought-after food, and they could be baked or dried for winter. They also were an important trade item. Other plants that women gathered included camas roots, wild artichokes, ground beans, plums, and chokecherries. George Catlin, North American Indians: Letters and Notes on their Manners, Customs, and Conditions (Newberry Library, Ayer 250 .C2 1926, v. 1, pl. 29).

Encampment of Piegan Indians

This camp of 400 tepees was near Fort McKenzie in 1833. Prince Maximilian and Bodmer visited at a time when the Piegans anticipated an attack from Assiniboines, so the tepees were pitched very close together. Note that the tepees vary in size. Poorer families had the smaller tepees, made of about eight buffalo cow skins stretched over a pole frame. More horses were needed to transport the large tepees than for the smaller ones. Wealthy men with several wives and many dependents had one or more large tepees, made with fourteen or more skins. Life on the plains required cooperation and sharing, so leaders, who were wealthy in horses, shared generously with others and provided poorer hunters with mounts. Note that men and women are bringing meat back to camp. Karl Bodmer also has drawn one of the men (lower left) with a white buffalo robe painted with designs that symbolized his war exploits. Engraving with aquatint (#43), after Karl Bodmer in Prinz Maximilian von Wied, Travels in the Interior of North America, 1832-34 (Newberry Library, oversize Graff 4649).

Crow Camp

George Catlin encountered the Crow in 1832 at the mouth of the Yellowstone River where Fort Union was situated. As the Crow moved to follow buffalo herds or traveled to trade with the American Fur Company, it was the woman of the household’s job to take down the tepee, fold and load the cover and attach the poles to her horse travois. Horses made this work easier, and elderly or infirm people, as well as children, could ride on horses or on a travois. In Catlin’s painting, note the buffalo meat that women cut into strips and hung in the sun to dry. Catlin also shows women working on hides they tanned for the use of the household or trade and men bringing meat into the camp. George Catlin, North American Indians: Letters and Notes on their Manners, Customs, and Conditions (Newberry Library, Ayer 250 .C2 1926, v. 1, pl. 22).

Camp of an Assiniboine Chief

Karl Bodmer made this drawing to illustrate Prince Maximilian’s atlas. Note that the image of a bear is painted on the tepee, which signifies that the bear spirit is a protector of the head of the household. The tepee has flaps that can be manipulated to direct the smoke from a cooking fire out of the tepee. The women of the household have arranged their travois upright to the left of the bear tepee. From this frame, they can hang equipment. Note also that the dogs are pulling smaller dog travois in order to assist the women with their work. Engraving with aquatint (#16), after Karl Bodmer in Prinz Maximilian von Wied, Voyage dans l’Intérieur de l’Amérique de Nord, 1840-43 (Library of Congress E165 W66).

Crow War Party

Karl Bodmer made this drawing of the Crow, whom he met at the mouth of the Yellowstone in 1833. Men belonged to warrior societies that protected and policed the camps and undertook war expeditions. A man who led a war party, either for revenge or for stealing horses, needed a record of success, which would have been associated with a spirit helper. Warriors carried objects that symbolized the power they had from spirits. Note the man carrying a fan: men carried fans of feathers from birds of prey, whose spirits assisted warriors. Acts of bravery brought a man prestige and status. For the Crow, the four greatest honors were touching an enemy, snatching an enemy’s bow or gun in hand-to-hand combat, stealing a picketed horse in a hostile camp, and leading a successful raid. Men painted symbols of their war honors on their clothes, their tepee linings or covers, and even their horses. When a successful war party returned, the men were praised in songs, and their wives danced with their husbands’ weapons, war regalia, or trophies, because the prayers that wives made on behalf of their warrior husbands were thought to be helpful. Engraving with aquatint (#13), after Karl Bodmer in Prinz Maximilian von Wied, Voyage dans l’Intérieur de l’Amérique de Nord, 1840-43 (Library of Congress E165 W66).

The Spaniard (His-oo-san-ches)

This young man probably had a Comanche father and a mother who was a Mexican or Spanish captive. Raised in a Comanche household, he grew up to be a leading warrior. The Comanches commonly took children and women captive on their raids. They might also take young Mexicans and use them as servants. Women often became wives of Comanche men, and children were adopted into Comanche families and became culturally Comanche. Comanches sold some of their captives to other groups, including Europeans who paid with guns and other trade goods. By the late 18th century, many captives were used as hostages that Comanches ransomed or exchanged for Comanche captives. By the 19th century, they preferred to adopt or marry captives in order to compensate for population losses due to epidemics brought by Americans moving west. George Catlin, North American Indians: Letters and Notes on their Manners, Customs, and Conditions (Newberry Library, Ayer 250 .C2 1926, v. 2, pl. 172).

Assiniboine Indians

Karl Bodmer painted these portraits at Fort Union, where the Assiniboines had camped to trade. Pitapiu (on the right) carries a rawhide shield with designs representing his spirit helper, and on the shield he has a bag containing additional “medicine power” from his helper for protection on horse raids. His bow-lance is draped with grizzly bear intestines dyed red, another source of medicine power. The man on the left has a hide shirt that is both quilled and decorated with glass beads obtained from traders. Both men have buffalo robes worn with the fur on the outside, indicating that the temperature is not extremely cold. Note that the shield is small, just big enough to cover the man’s organs. When men began to fight on horseback, their bows had to be shorter and their shields smaller. Engraving with aquatint (#32), after Karl Bodmer in Prinz Maximilian von Wied, Travels in the Interior of North America, 1832-34 (Newberry Library, oversize Graff 4649).

Buffalo Back Fat

This man’s portrait was painted by George Catlin at Fort Union at the mouth of the Yellowstone River. Buffalo Back Fat was the head chief of the Blood division of the Blackfeet confederacy and fifty years old. He wore his finest cloths: a shirt of two deer skins with quill embroidery on the chest and, on the seams of the sleeves and leggings, bands of quill embroidery and fringe made of hair from the heads of enemies he had killed. His moccasins also were ornamented with quills. He had six wives, who produced many buffalo robes for trade with the American Fur Company and also made his fine clothing. He dealt with the traders to make arrangements for his people to engage in trade, and he also met with representatives of the federal government on his people’s behalf. He had a peace medal from President Thomas Jefferson (not worn here), and he carries his pipe, which he smoked with the head trader before they settled on trading protocol. George Catlin, North American Indians: Letters and Notes on their Manners, Customs, and Conditions (Newberry Library, Ayer 250 .C2 1926, v. 1, pl. 11).

Eagle Ribs

This man was a great warrior among the Blood division of the Blackfeet. In fights with trappers and traders, who the Blackfeet tried to keep out of their hunting territory, he took eight scalps. In Catlin’s portrait he wears a headdress of ermine skins and buffalo horns (reserved for the most distinguished of warriors). On his lance are two otter skin medicine bags. One medicine bag was obtained in a vision quest in which he established a personal relationship with a spirit helper and the other was taken from an enemy he killed. George Catlin, North American Indians: Letters and Notes on their Manners, Customs, and Conditions (Newberry Library, Ayer 250 .C2 1926, v. 1, pl. 14).

Sioux Body Sacrifice

Catlin found this group of Teton Sioux at the mouth of Teton River. The Sioux were camped near Fort Pierre in the spring in order to trade. Catlin shows an individual making a body sacrifice to accompany a prayer for success in some endeavor. This kind of sacrifice demonstrated sincerity to the spirit world. The man has skewers through his chest that are tied to a cord on a pole. As he leans back, the skewers are pulled until the skin tears away (or it is cut free at the end of the day). The man holds his bow and medicine bag. Other men sing and encourage him. Religious life revolved around the spirit world, and the buffalo spirit was of central importance in creation stories. The buffalo skull in this painting represents the buffalo spirit, which usually figures importantly in religious ceremonies because the buffalo symbolizes life itself. George Catlin, North American Indians: Letters and Notes on their Manners, Customs, and Conditions (Newberry Library, Ayer 250 .C2 1926, v. 1, pl. 97).

In the early 20th century, Plains tribes began to advocate for control over the management of the mineral resources on their reservations and over the disposition of the mineral income. They struggled to retain subsurface mineral rights and to persuade the government to promote energy development and obtain market value prices for their oil, gas, and coal. After the Indian Reorganization Act, tribal leaders had some success in gaining control over mineral income, especially in obtaining per capita payments to mitigate poverty. In 1938, in response to tribes’ complaints that their mineral lands were leased at below market value, Congress passed legislation that required competitive bidding. In the 1970s, complaints about air and water pollution led Congress to grant the tribes authority in 1986 to set air and water quality standards. Aided by the Council for Energy Resource Tribes (organized in 1975 with mostly Plains and Southwest tribes), tribal leaders developed expertise in environmental and monitoring issues. Partly in response to the tribes’ discovery of energy company thefts of tribal minerals, Congress passed the Indian Mineral Development Act in 1982, which authorized tribes to develop their minerals through regulation, negotiation (for jobs, environmental quality, monitoring and accounting), and joint ventures with energy companies. Also that year, the Supreme Court authorized tribes to tax mineral production on their lands. Leases, royalties, bonuses, and taxes have been the major source of income for Wind River, Blackfeet, Crow, Northern Cheyenne, and Fort Peck, and these reservations continue to struggle to defend their resources. That said, the members of the “energy tribes” are not “rich Indians”: the reservation populations are large enough so that the per capita shares of the income are small and few energy jobs go to Indians.

How do reservations that lack mineral wealth, like Pine Ridge and Rosebud, try to improve economic conditions? These Sioux (or Lakota) live as members of large households of relatives who pool their labor and income. A household may have only one or two people working full-time for wages, but the other members contribute income from part-time wages, social security or pensions, or public assistance, and possibly a little income from ranching or a small business. Others hunt and fish, babysit or do housework, and in over 80% of the households people engage in microenterprises. These businesses, run out of the home, bring in income or goods in exchange. The Pine Ridge Sioux and the Rosebud Sioux have very limited funds for economic development, but both work to obtain contracts and grants so they can hire tribal members. Programs provide low-rent housing and educational grants, and health care is available from the Indian Health Service. Of course, tribes with money from oil and gas wells and coal mines have more income to hire their members, support education, and offer services to mitigate the effects of poverty.

All the Plains tribes and their members pursue the sovereignty agenda of self-rule and self-sufficiency in various kinds of social activities and programs that affirm identity. Some tribes have historically resisted assimilation to Western values and customs, so the sovereignty era has meant that they can openly practice their traditions. Others, who experienced a significant decline in Native ceremonies, language, and sharing customs, embarked on a process of cultural revival. The American Indian Movement was very active on the Plains, especially at Pine Ridge and Rosebud, and AIM’s advocacy for sovereignty and Native culture had a major influence on Indian youth in the late 1960s and 1970s. Generally, identity in these Plains communities is reaffirmed (and often reinterpreted) in several ways. Skill in horsemanship is important and often is expressed in rodeo participation. The reintroduction of buffalo herds is widespread, with some tribes primarily using the buffalo for food, others for commercial sale, and others to reinforce community unity through ceremonial feasts. Native religious ritual has undergone a revival. In the case of the Crow, that revival began during the New Deal. For others, such as Fort Belknap, the revival process began in the 1970s. Powwows are always vehicles for the expression of individual and tribal identity, the revitalization of music traditions, understandings about kinship, and the occasion for “giveaways,” in which the values of generosity and sharing are reinforced. The tribalization of education also is widespread, with reservation communities asserting control of the schools on the reservation and establishing tribal colleges and Native language programs. And rituals that reinforce collective memory are important, especially in respect to massacres (such as Wounded Knee, Sand Creek, or Baker) or in relation to sacred sites (such as the Black Hills).

Plains Cultural Identity

Buffalo Herd, Fort Belknap Reservation

In 1902 Congress appropriated money to keep bison from captive populations (for example, zoos) in Montana and Texas in a corral in Yellowstone National Park. By this time, the bison or buffalo were practically extinct. The Yellowstone bison had protected status in the park and their numbers grew. But when animals strayed out of the park, Montana residents shot them and the herd began to decrease. In 1990 the Intertribal Bison Council organized to assist tribes in obtaining these bison and moving them to Indian reservations. Some tribes, such as the Fort Belknap Gros Ventre and Assiniboine, already had small herds. The tribes started the herd in 1974 with 35 animals and made 15,000 acres of tribal land available for pasture. Now at Fort Belknap, the 400 or more buffalo have one or two percent cattle genes, and the tribes want genetically pure wild bison from Yellowstone. In 2011 the Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks Commission agreed to transfer some bison from Yellowstone to Fort Belknap and also to Fort Peck, and the tribes agreed to fence off pasture for them to prevent straying. Much opposition developed in the state, and the state court stopped the transfer to Fort Belknap. Some bison reached Fort Peck before the restraining order was issued. Buffalo herds exist on Crow, Northern Cheyenne, Blackfeet, and Fort Peck reservations, as well as on Fort Belknap. The herds are important culturally: the meat is used for ceremonies and often for health programs, and the buffalo symbolizes Indian identity and religious tradition for these tribes. Photo by Randy Perez.

Crow Fair

The Bureau of Indian Affairs introduced agricultural fairs on Indian reservations in order to encourage farming and an American life style generally. Indian agents encouraged exhibits of crops, livestock, sewing, and canning. The agents hoped the fairs would replace the traditional summer tribal gatherings. The Crow Fair held in 1904 was the first of these agricultural fairs (on Fort Belknap reservation, the Gros Ventre’s Hays Fair was started soon afterwards). The Crow began to include traditional activities, and gradually the fair became a reservation-wide fall gathering where the Crows danced, played Indian games, exhibited Crow art and handicrafts, had sham battles, and held races and rodeo events. By 1914 Crow officers and district communities had begun to take over the management of the fair, and by 1923 it was completely under Crow management. During the New Deal, the Crow superintendent Robert Yellowtail (himself a Crow) moved the date of the fair to August and encouraged Crow nationalism by promoting the fair and rodeo, and he tried to display Crow culture in a positive light by advertising the fair to attract non-Indians (including famous politicians and others). He facilitated the revival of Crow ceremonies at the fair and worked to build up a buffalo herd. Yellowtail also supported an impressive parade—Crow officials, veterans, surviving scouts, clan leaders, dancing societies, and community organizations. The Crow also held political meetings at the fair. By the 1960s, the Crow Fair was widely advertised as the “tepee capital of the world.” Crow families put up tepees for themselves and their guests and camped at the week-long fair. The number of tepees approached 1,400. During the fair, Crows participate in activities that reinforce Crow identity, including singing competitions, religious ceremonies, powwow dancing competitions, giveaways (especially those between individuals and their clan uncles and aunts—the Crow are the only upland Plains tribe that has a clan kinship system, which dates back to their Hidatsa heritage), and feasts for guests. Photo by Montana Film Office.

Crow Fair Rodeo, 2010

On their reservation in the late 19th century, Crow families tried to ranch and also to continue their tradition of horsemanship by racing with Indians and non-Indians. Some worked in wild west shows where they observed cowboy exhibits of riding and roping. The Bureau of Indian Affairs introduced an agricultural fair at Crow in 1904 and a small rodeo became part of the fair. By 1923 Crows had taken control of the fair and the rodeo, and rodeos became associated with American holidays, such as the Fourth of July. Crow cowboys began participating in regional rodeos alongside non-Indian cowboys. When Robert Yellowtail became superintendent at Crow Agency (his home agency) in 1934, he promoted the rodeo as well as the fair itself. Yellowtail wanted to attract tourists, reinforce pan-Indian identity, and develop Crow nationalism. The rodeo opened with a parade of cowboys on horseback in traditional dress. There were four days of horse races, where betting was common. Events included steer roping, bronco riding, calf roping, and, to attract tourists, buffalo riding. Crow families raised most of the stock used. Women gradually became contestants in barrel racing and breakaway roping, directors of events, and rodeo princesses. Particular families emerged as “rodeo families,” famous for their achievements across the American West. In the 1950s and 1960s, an all-Indian rodeo circuit emerged along with several organizations for Indian rodeo participants. Intertribal rodeos increased in popularity in Wyoming, Montana, and the Dakotas, often associated with powwows. By the 1970s the Crow rodeo had become the second largest all-Indian rodeo. Crow trick riders were known for their bareback relays where riders moved from mount to mount. In 1976 an Indian National Finals Rodeo attracted Crow cowboys and cowgirls. Today high schools and tribal colleges have rodeo teams, and reservation communities often have rodeos for charity events or memorials. On Crow reservation, the Crow rodeo is part of individual and collective identity and a source of pride for families and the tribe. It is part of the continuation of horse and cattle culture on Northern Plains reservations and is viewed by Crows as representative of native tradition. Photo by Cynthia St. Charles.

Wounded Knee Memorial Ride, 2011

In December 1890, a group of Minneconjou Sioux led by Big Foot (a Ghost Dance leader) left Cheyenne River reservation on their way to Pine Ridge reservation, where Big Foot had been summoned to a council. Big Foot’s people were surrounded by troops and forcibly marched to Wounded Knee Creek on Pine Ridge. On December 29, while under guard from troops from the 7th Cavalry, the officers ordered the men and youths to separate from the women and children and to turn in any weapons they had. As their weapons were collected, the men sang death songs. Someone fired a shot and the troops opened fire, killing most of the men. Then they turned a machine gun (hotchkoss) on the women and children. More than 150 men, women, and children in Big Foot’s band died. Survivors were attacked as they fled. The victims' descendants live today on several Sioux reservations. Why was Big Foot attacked? For years Congress had been cutting the budgets for rations. By 1890, the Sioux were receiving less than half of the promised rations. They suffered from malnutrition and starvation, which made them particularly vulnerable to disease. In despair, when they learned about a new religion, the Ghost Dance, that offered hope, they embraced it. This new religion was started by a prophet named Wovoka, a Paiute living in Nevada. By following Ghost Dance ritual, he explained, the buffalo would return, non-Indians disappear, and deceased relatives reunite with the living. The new religion spread to most Plains reservations, where followers went into trance and saw the new world in their visions. Among the Sioux, a leader’s vision promised that the wearing of a special shirt would protect the wearer from harm by non-Indians. Federal officials felt threatened by the Ghost Dance, and troops were sent to South Dakota to arrest leaders and prevent Ghost Dancing. The result was the infamous Wounded Knee Massacre. The first Chief Big Foot Memorial Ride took place in 1986, when riders retraced the movements of Big Foot’s group as they traveled to Pine Ridge. Beginning ceremonies are held at Standing Rock reservation, where Ghost Dance leader Sitting Bull was killed, and ending ceremonies at the mass grave of Big Foot’s people on Pine Ridge. The ride has been repeated annually since 1986, with the riders (largely youths) making the two-week journey on horseback in December. They camp at the end of the day, and elders teach them about Sioux culture and history. Youths come from several Sioux reservations to participate. The ride is both a spiritual and an educational experience for participants: the Sioux must never forget the suffering of their ancestors and also recognize that the Sioux Nation has survived this and other terrible events and conditions. Photo by Duane Kuntz, Great Plains Examiner.

There are other regions where Indians are a sizable population and own large parcels of land. How do these areas compare with the Great Lakes and the Plains in terms of economic development?

In metropolitan areas, Native people generally are integrated into the wider economy. Their tribally-owned businesses in these urban areas are often very successful enterprises that hire large numbers of tribal members, and non-Indians as well. In contrast, in sparsely populated, rural America, tribal members have more difficulty finding permanent employment and tribal businesses are marginally profitable or have only a small number of employees. The Northeast, Southeast, California, Pacific Northwest, and Southwest are metropolitan sectors of the United States, which are heavily populated and densely settled areas with centers of commerce, finance, and industry.

In the NORTHEAST, the members of Native communities have been integrated into the wider economy for generations, often working in towns and cities within commuting distance from their communities. Some states have established reservations, and there are also a few federally recognized tribes with trust land—two in Connecticut, one in Massachusetts and Rhode Island, five in Maine, and nine in New York (including reservations for the Seneca, Oneida, Onondaga, Mohawk, and Tuscarora). The two tribes in densely populated Connecticut (Pequot and Mohegan) are economic powerhouses employing thousands of non-Indians as well as tribal members in their resort-casinos. Some of the New York tribes in urban areas (Buffalo, Niagara Falls, Syracuse) have businesses, including profitable casinos.

Scattered through the SOUTHEAST are small, rural Native communities that historically were disadvantaged by a racial hierarchy and whose members are integrated into the wider economy, many employed in urban areas. Some tribes have small reservations established by states. The few that are federally recognized (one in North Carolina, Alabama, South Carolina, Mississippi; three in Texas; four in Louisiana; and five in Florida) have some trust land and can operate businesses and services. The Seminole in Florida have very profitable resort-casinos and other businesses. In eastern Oklahoma are tribes with large populations and significant economic development, including all sorts of tribally-owned businesses in addition to casinos and resorts (the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole).

In CALIFORNIA the many Native communities are small in size and population after a long history of dispossession and genocide. These communities have been integrated into the wider economy, where metropolitan areas offer a variety of employment opportunities and where, in rural communities, Indians had low-paying jobs. The state rejected the idea of treaty reservations, so few groups had reservations before the 1930s. In the New Deal era, the federal government established 117 Indian communities but terminated (removed the trust status of their land) about half in the 1950s. In 1963 there were over 65,000 Indians in California and, due to a class action lawsuit in 1983, many communities were restored. Now there are over 113 federally recognized Indian reservations or rancherias (very small reservations) in California. Few have more than 500 members. Federal recognition and a land base, however small, make it possible for tribal governments to succeed at economic development, provide social services, and support cultural renaissance. In rural areas, distant from metropolitan areas and interstates, the tribes work on small projects, often agricultural. In metropolitan areas—such as the vicinity of San Diego, Los Angeles, or Palm Springs—and near interstate highways, the tribes have developed many profitable businesses, including resort-casinos, and have become major employers, for non-Indians as well as Indians.

The SOUTHWEST has 45 federal reservations. The Arizona and New Mexico region is a metropolitan area, although there are some rural areas where there are large reservations on which the tribe is the major employer and there is high unemployment. On small reservations near urban areas tribal members work for wages on and off their reservations and unemployment is low. In Arizona near Flagstaff is the large Hopi reservation (villages atop mesas surrounded by farm land) where the tribal government earns a high income from oil, gas, and coal, and Hopis work mostly for the coal company and in the tourist industry. Also in Arizona are the mostly small “Yuman” and the Pima and Papago reservations, where many tribal members obtain jobs in Phoenix and Tucson, and tribal governments operate profitable casinos near cities and interstates, as well as support agriculture and other jobs. There are 19 Pueblo (villages surrounded by agricultural lands) reservations in New Mexico that have small land bases and serve as ceremonial centers for their members who work in nearby Albuquerque or Los Alamos. On most, tribal governments operate resort-casinos and tribal members also work in the flourishing tourist industry. In New Mexico and Arizona are four large Apache reservations that are more remote and largely agricultural. Unemployment (up to 68%) is a problem despite the tribes’ ownership of casinos or other businesses. The 17 million acre Navajo reservation (one-fourth of the state of Arizona, part of New Mexico, and a small section of Utah) has a huge enrolled population (upwards of 180,000). In this vast rural region are small, sparsely settled communities where Navajos raise corn, sheep, and manufacture jewelry and other items to sell. The tribe has a high income from oil and gas, coal, and uranium but cannot create nearly the number of jobs needed, so unemployment is high (52% in 2005). Navajos work for the coal mines, tribally-owned shopping centers, and tribal forestry. Navajos have a long history of working for wages in the region, and a large sector of the membership lives and works off the reservation.

In the Pacific Northwest Coast and Columbia River system in Washington and Oregon, there are 39 federal reservations. These have small memberships—most number less than 1,000. Along the coast tribal members do both subsistence and commercial fishing, as they have for generations. These activities grew in importance after the Boldt decision in 1974, in which the federal courts established treaty rights to half the fish for treaty signatories. Native fishermen may still face difficulties due to lack of capital and environmental degradation. Cultural renaissance is built on the fishing rights struggle and tribal involvement in commercial fishing and protection of the environment. Near the urban areas of Seattle, Spokane, Tacoma, and Portland some tribes have resort-casinos that are profitable. The median unemployment in Washington is comparable to that in the Great Lakes, and in Oregon it is a little lower than in the Great Lakes area. In both regions, the median unemployment is considerably lower than in the Plains, which is more rural and lacks a strong commercial economy.

The region most comparable to the upland Plains is the Desert area of Nevada and Utah—a sparsely populated, rural area. Here there are 32 federal reservations for Shoshones, Washoes, Utes, and Paiutes. Most are very small settlements with small populations, where tribal members have worked for ranchers or townspeople for low wages for many generations. Many also do subsistence hunting, fishing, and gathering. After tribal governments began contracting programs, more jobs were available but in these remote, sparsely populated areas, most did not have casinos or other businesses with large numbers of employees. These desert reservations have been the target of efforts to dump nuclear and other hazardous waste. The Paiute settlements in Las Vegas and the Moapa reservation near there have a profitable resort and casino, respectively. The large, remote Walker River reservation in Nevada has 77% unemployment and little tribal income. The large Pyramid Lake reservation in Utah attracts vacationers, especially fishermen, and some tribal members ranch but there is relatively high unemployment here even though the reservation is within commuting distance of Reno. The largest reservation is the one- million- acre Uintah Ouray in northeast Utah, which has a very large income from oil, but 77% unemployment. The 3,000 tribal members hunt and fish and do some ranching, and the tribe has invested in manufacturing and other businesses.

So the contrast between metropolitan and rural regions in the U. S. is an extremely important factor in how successful tribes can be in developing businesses and reducing unemployment in their homelands. A comparison of the Great Lakes and upland Plains unemployment and median household income is a good example. To understand the disparity between the tribes, one must understand the relative urbanization of their respective regions. For example, the population of Montana in 2000 was 902,195 (and the population density was 6.2 persons per square mile), while the population of Wisconsin was 5,363,675 and the population density, 98.8.

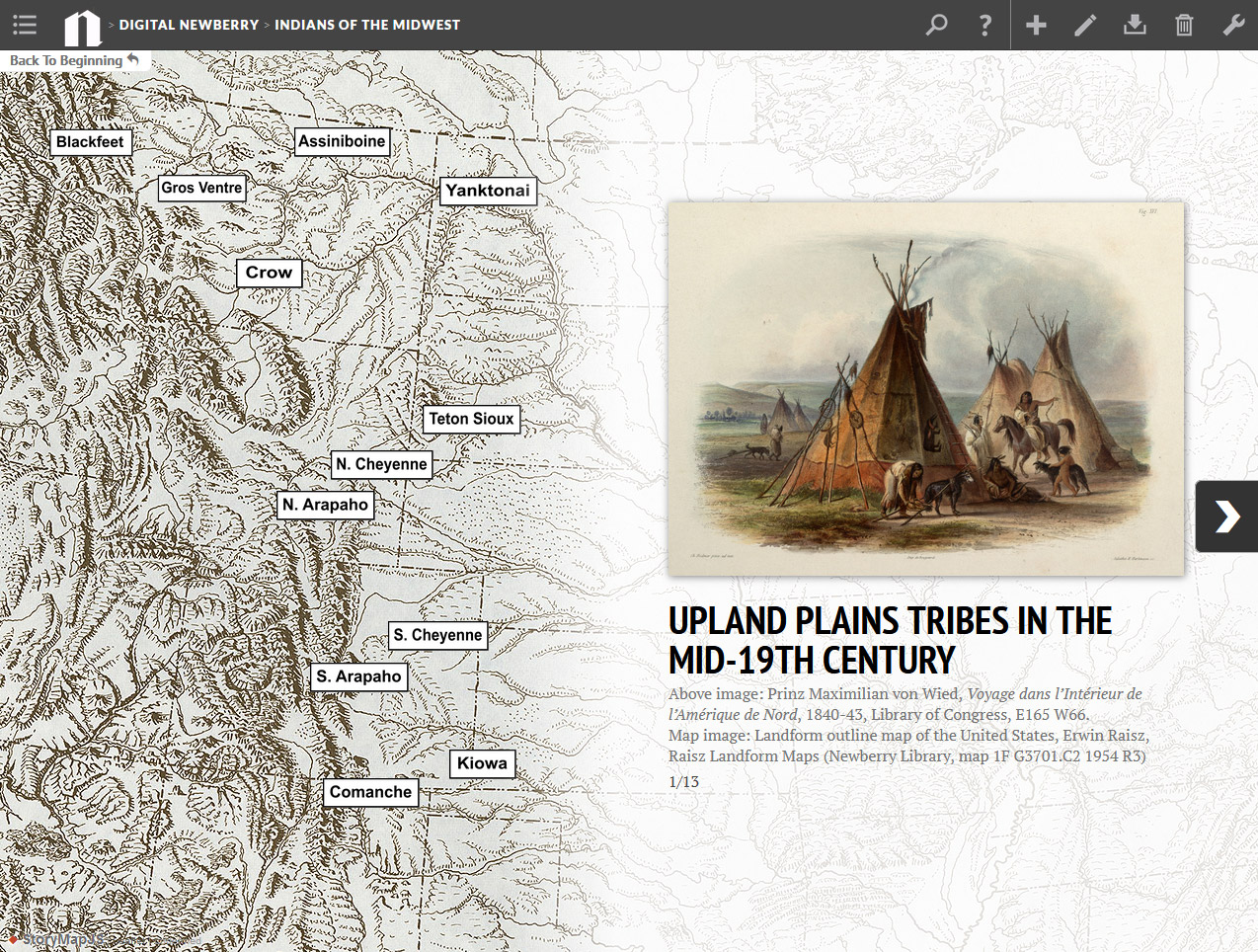

Interactive map: Explore the Upland Plains Tribes in the Mid-19th Century

Interactive map: Explore the Northern Plains Reservations, 2012

Crow Cowboys, ca. 1890

These men are branding cattle at a ranch on the Crow reservation. In 1884 the Crow were at their agency subsisting on rations for 52 weeks that were adequate for only 17 weeks. Their leaders appealed to Congress to send them cattle. They argued that they would pasture the cattle at the foot of the mountains and along creeks, caring for them so that they would produce calves and the herd would increase over time. Congress did purchase cattle for the Crows. From then on, Crows remained involved in both individual and communal ranching. The ranchers worked in groups as they cared for the cattle and shipped them to market. Photo courtesy of Montana Historical Society Research Center Photograph Archives, Helena, MT.

Oil and Gas Drill Rigs, Blackfeet Reservation

The Blackfeet tribe relies on income from oil and gas fields to fund social and economic programs and make periodic per capita payments. Like other "energy tribes" on the Plains, their leaders struggled for years to maximize this income and control energy development on the reservation. Elected leaders successfully lobbied Congress to stop the sale of "surplus" land on the reservation and recognize tribal ownership of subsurface minerals on allotments. Leaders worked for years to force production on the lands leased for oil and gas, despite federal opposition. In 1926 there was still little oil development and no royalty income for the tribe. New leases were not approved and old leases were not enforced. Blackfeet leaders argued that oil drilling near the reservation threatened to drain tribal reserves. Finally in 1932 these leaders obtained a new lease, and the following year there was an oil strike and a per capita payment. But in 1934, there were only three operating wells. The Blackfeet accepted an IRA government during the New Deal era largely because the new 1936 constitution gave Blackfeet leaders the authority to manage the disposition of money from their oil and gas. Still, the secretary of the interior could veto leases. Leaders continued to protest. After 1940, oil prices rose, and in 1943, 64 tribal leases provided $300,000 for the tribe. Some of the income was used to develop ranching and some for per capita payments. In the 1950s about half the mineral income was used for per capita payments. In 1955, the Blackfeet received the largest ever per capita payment, $225. In 1975, during the era of tribal sovereignty, Congress turned over some submarginal lands (with mineral rights attached) to the Blackfeet, and the tribe negotiated an oil and gas contract that provided for joint management and profit sharing. In 1981, tribal members received a per capita payment of $1, 317. In the 1980s, the tribe discovered that the Bureau of Indian Affairs had not been monitoring the wells competently, and thefts of oil had occurred, so the tribe fought for and got expanded authority to monitor the oil companies. The Indian Mineral Development Act of 1982 allowed Indian tribes to regulate, negotiate, and monitor energy development on their reservations. That year the tribes also were authorized to collect severance tax from energy companies producing on their reservations. The state of Montana sued for the right to also tax tribal mineral income and lost the case in 1985 in the Supreme Court. About 90% of the Blackfeet tribe's income comes from oil and gas leases, royalties, bonuses, and taxes. Photo by Tony Bynum.

Microenterprise, Arrow Barber Shop

This is Louis Young, a member of the Oglala Tribe of Pine Ridge reservation, standing beside his barber shop. After he retired, he decided to use the training he received in the 1970s, when he studied to be a barber, so he got a microloan from Lakota Funds to establish his Arrow Barber Shop. He built the shop himself on his own land. He has subsequently repaid the loan. Mr. Young has worked for a year and a half to build up a clientele. His clients, largely veterans, no longer have the expense of driving long distances to off-reservation barber shops. Lakota Funds is in Kyle, on the Pine Ridge reservation. It was established in 1986, with the help of Oglala Lakota College and the First Nations Development Institute, in order to provide capital and technological assistance for aspiring entrepreneurs among the Sioux population. At the time, there were only two Indian-owned businesses on Pine Ridge. Lakota Funds began as a micro lender modeled after Circle Banking Project in Bangladesh, loaning up to $500 (secured or unsecured) to a client. The organization also makes credit bundle loans to help individuals pay off delinquent loans, provides training for entrepreneurs, and teaches youths fiscal literacy. Since its inception, Lakota Funds has loaned over 6 million dollars to help 450 businesses on or near Pine Ridge. Now the maximum loan is $200,000. There are 13 businesses for every 1,000 reservation residents compared to 83 per 1,000 South Dakota residents, and there is high unemployment on Pine Ridge, so Lakota Funds is important in reservation economic development. Photo courtesy of Lakota Funds ©2012.

Do you want to do your own research?

This page has paths:

This page references:

- Encampment of Piegan Indians

- Eagle Ribs

- Winter Hunt

- Buffalo Herd, Fort Belknap Reservation

- Crow Cowboys, ca. 1890

- Capturing Wild Horses

- Crow War Party

- Buffalo Back Fat

- Assiniboine Indians

- Microenterprise, Arrow Barber Shop

- Camp of an Assiniboine Chief

- Crow Camp

- Blackfeet Indians on Horseback

- Crow Fair Rodeo, 2010

- Fire Bug That Creeps, Assiniboine Woman

- Indians Hunting Buffalo

- Sioux Body Sacrifice

- Crow Fair

- Oil and Gas Drill Rigs, Blackfeet Reservation

- Wounded Knee Memorial Ride, 2011

- The Spaniard (His-oo-san-ches)